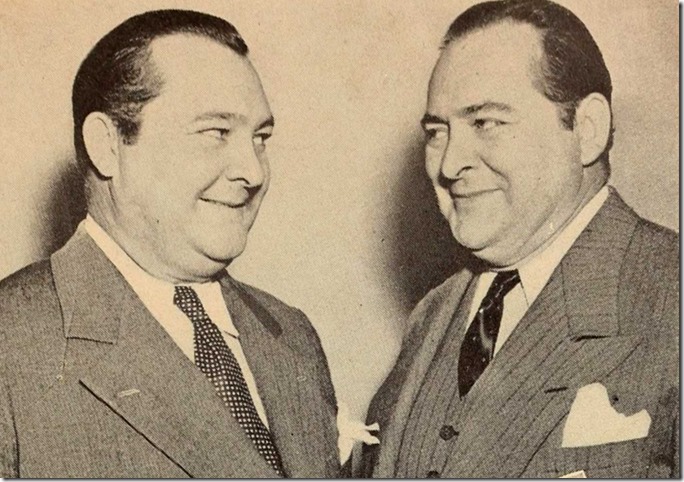

William Hoover, left, doubled for Edward Arnold, Silver Screen, August 1939.

Since 1927, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has recognized best acting performances in motion pictures by male and female stars. They began recognizing best supporting performances in 1936. Directors, writers, cinematographers, costume designers, and production designers are also honored, not only by the Academy but by each of their individual guilds, and now by critics’ groups, festivals, and even by the people.

Long forgotten by the industry and even audiences, stand-ins fought to be recognized for their own contributions to the creation of motion pictures. For a short time in the 1940s, this little acknowledged group handed out their own awards. Instead of being able to say, “I’d like to thank the Academy,” they could thank the stars for whom they tolled under hot lights and conditions.

“Hollywood Celebrates the Holidays” by Karie Bible and Mary Mallory is now available at Amazon and at local bookstores.

Victor Chatten, was the stand-in for Lew Ayres, Silver Screen, August 1939.

The use of stand-ins, replacing someone else in something onerous or dangerous, dates to the mid-teens when doubles or stand-ins replaced actors during difficult stunts in serials. Tony Slide in his book “Hollywood Unknowns” states that the earliest documented use of a stand-in dates to 1914, when D. W. Griffith substituted Claire Anderson for the ailing Blanche Sweet (she was suffering from scarlet fever) in some of the scenes for his film “The Escape.”

He also claims that the traditional use of stand-ins originated in the 1920s with the sometimes temperamental actress Pola Negri during her days at Paramount. Brought to America by the studio in 1923, Negri disliked waiting around the set when not working and suggested that a mannequin or dummy replace her during this time.

As early 1928, Screenland magazine mentions Betty Danko, Corinne Griffith’s stand-in for “The Divine Lady,” calling stand-ins a recent addition to filmmaking. The practice began to catch on, and studios hired lookalikes to replace the actors while directors and camera crews adjusted the lights, arranged staging, and set up for shooting.

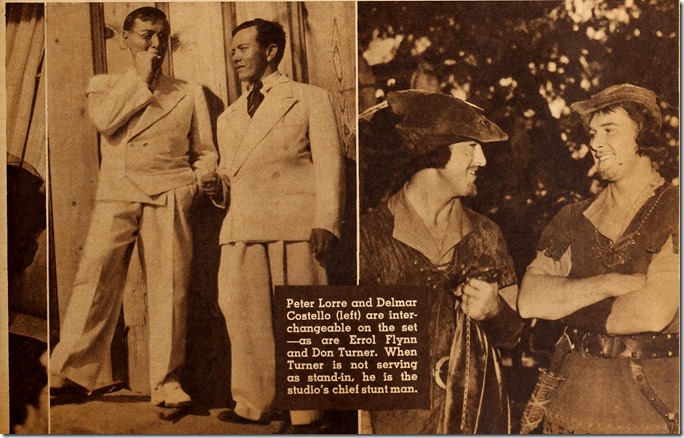

Peter Lorre and Errol Flynn and their doubles, Modern Screen.

Articles began appearing in fan magazines about the profession, calling it perhaps an opportunity to break into the business, as readers inquired about the practice. Many of these stories included photos of stars with their stand-ins; some could be dead ringers for those they doubled, while others merely possessed the same height, body build, and hair color of their doppelganger. Some of the players became bosom buddies with their bosses, while others merely hobnobbed on the set.

Most stand-ins never achieved fame on their own, and worked rarely outside of this profession. Some, however, did go on to gain success. During silent days, many believe Buck Jones acted as stand-in and valet for star William Farnum, though the two possessed entirely different body types. Dashing Don Alvarado appears to have stepped-in for superstar Rudolph Valentino. Later in the 1930s, a young Ann Dvorak worked as Joan Crawford’s stand-in at MGM. Actress Julie Hayden stood-in for Ann Harding at RKO.

Jeanette Rudy, left, was the stand-in for Martha Raye, Silver Screen.

Some who had been famous during early filmmaking fell back to stand-in work later in their careers. Variety noted that cowboy star Lane Chandler worked as Gary Cooper’s stand-in for Hollywood shooting of “The Plainsman.” Little Carmen La Rue served as Dolores Del Rio’s stand-in. Baby Marie Osborne, star of Balboa Pictures, worked as Ginger Rogers’ stand-in during the 1930s, and after a short return to working before the camera, became Deanna Durbin’s stand-in in the early 1940s.

In 1937, dancer Mary Dees was hired to double for the recently deceased Jean Harlow in order to complete her last film, “Saratoga.” While Dees did possess a similar hair style and build to that of Harlow, it was still obvious that the actress seen only from the back in later scenes was not Harlow.

The use of the word “stand-in” began appearing in popular culture, with silent actor Charles Ray penning a short story in 1935 called “Stand-In,” which also later served as the title of a 1937 film starring Leslie Howard, Humphrey Bogart, and Joan Blondell, in which a New York banker learns all about the motion picture industry from a stand-in. The film “It Happened in Hollywood” featured a down-on-his-luck cowboy star (Richard Dix) who enjoys the companionship of his friends, the stand-ins. “Screen Snapshots” included a sequence about stand-ins at Columbia also in 1937.

George Raft, left, with stand-in Mack Grey, Photoplay, 1933.

By 1939, New York columnist Ed Sullivan wrote in Silver Screen magazine about the hard life of stand-ins, who only made money on the days they actually doubled for their stars, since they rarely appeared as extras in their own right. Thanks to the Screen Actors Guild, below-the-line talent pay had increased under the 1937 bargaining agreement, with extras earning up to $15 a day, while stand-ins received $23 a week or $6.50 a day.

Stand-ins attempted to form their own guild in 1939 to better their conditions when they organized the Hollywood Standin (sic) Players, Inc., before later changing its name to the Hollywood Stand-Ins Guild. By the 1940s, the Associated Stand-Ins of Hollywood represented the workers. They decided to honor their own with awards beginning in 1942.

Showman’s Trade Review reported March 14, 1942 that stand-ins “stood-in” for such stars as Gary Cooper, Randolph Scott, Marlene Dietrich, Ole Olsen, Chic Johnson, Hugh Herbertt, Leo Carrillo, Deanna Durbin, and others at the unusual “Hellzapoppin” premiere at the Hawaii Theatre, with many of the stand-ins appearing in public for the first time as their screen lookalike. They appeared after attending a Brown Derby banquet for presentation of “Elmers” “for the “best stand-in performances” of the year to Sally Wood, stand-in for Marlene Dietrich, and to Frankie Van, stand-in for Hugh Herbert.” Following the banquet, the guests were chauffeured in limousines with footmen to the Hawaii Theatre, where they were greeted by photographers.

Joan Blondell, center, with her stand-in, Jean Blair, left, and Iris Lancaster, a stand-in for Joan Crawford, Photoplay, 1933.

The article does not mention how the winners were selected for best stand-in, if they went beyond the call of typical duties, or performed some special service. At least for once they were recognized for the hard work they endured in finishing motion pictures.

On March 15, 1944, Variety announced the winners of the “Elmers” awarded by Associated Stand-Ins of Hollywood the night before: Jack Parker, Randolph Scott’s stand-in for “Gung-Ho” received the award for best male stand-in, while Sally Wood won the best female stand-in award for her work replacing Susanna Foster in “This Is the Life.” No mentions of the Elmers appear again in the trade papers, suggesting the award ceremony disappeared.

There is no exact explanation for where stand-ins acquired the name “Elmer” for their awards. There is one possibility. The term possibly arose from the New York World’s Fair publicity department hiring a typical American friendly greeter. As the Motion Picture Herald stated in its June 29, 1940 issue, “Elmer” was the hypothetical typical American, hail fellow, genial, a sucker for sentiment, fond of popcorn, and with a merry “Hello, Folks,” for everybody.” Mr. Leslie Ostrander, a professional model from Brooklyn, served as their first “Elmer.”

In the 1970s, Amateur Radio began presenting Elmers to those they considered mentors or supporters of would-be ham operators, after the term was first used in a March 1971 article in QST. Elmer is an appropriate name for those who support and serve others, often receiving no great thanks or remuneration in return.

While the Academy Awards remain the motion picture industry’s preeminent award for excellence, the lowly Elmers are long gone and forgotten, though they also rewarded quality work by those who merely stood around and waited.

Mon Dieu! You just made me realize that Edward Arnold and Eugene Pallette could have stood in for one another! One of them would have made for delightful company.

LikeLike