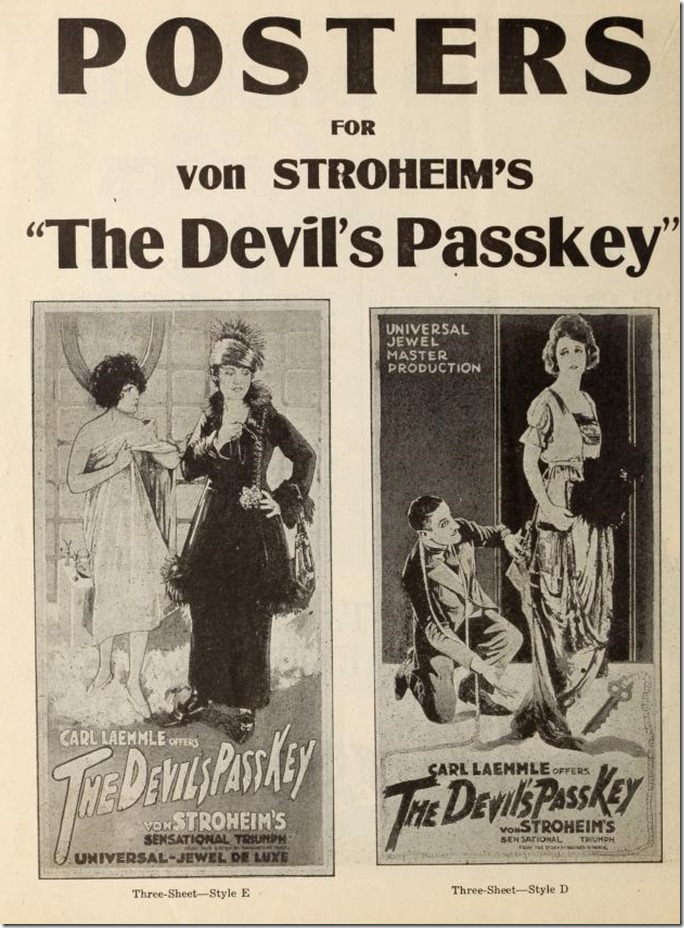

A poster for “The Devil’s Passkey.”

Riding high on the wave of great reviews and huge box office for “Blind Husbands,” his first film as director, artistic Austrian Erich von Stroheim expanded his horizons with his second film, “The Devil’s Passkey.” Rushed into production after Universal Studios realized the box office potential for “Blind Husbands,” ”The Devil’s Passkey” allowed the young director more freedom to experiment. Would freedom be a blessing or curse for the overly confident director?

“Blind Husbands” turned out well for both the director and studio. von Stroheim revealed a master’s eye for detail in story, capturing character in a line or side glance. He kept both himself and his actors restrained in telling a mature tale, one hinting at depravity without crossing the line. Most importantly, he stayed reasonably within budget; Arthur Lennig in “Stroheim” reveals he spent $125,000, slightly more than the average Universal budget, on his film. Costs stayed relatively within budget by filming the Alpine scenes at Big Bear and Idlywild, and focusing more on simple sets.

Mary Mallory’s “Hollywoodland: Tales Lost and Found” is available for the Kindle.

Posters for “The Devil’s Passkey.”

Director von Stroheim envisioned greater things for his follow up motion picture, selecting a story set in the rich milieu of continental Paris. Based on Baroness de Meyer’s unpublished story, “Clothes and Treachery” looked at the extravagant American, Mrs. Goodwright, willing to do almost anything to cover her financial embarrassment. The plot’s focus on a young, self-absorbed woman living beyond her means and trying to hide it from her husband echoed somewhat the stories of “The Cheat” and “Blind Wives.” von Stroheim threw his own curve ball into the story by making her husband a playwright, who discovers the story without knowing the characters and adapts it into a successful play. Both must suffer and absorb the embarrassment of profiting off of a story revealing one’s moral shortcomings.

Actor Leo White suggested the story to the director, per the January 28, 1920 Bridgeport Times, with von Stroheim spending a few months adapting it for his more louche character details. During production the title constantly evolved. Starting production under the moniker “Success,” the film underwent a series of name changes: “Charge Account,” “the Woman in the Plot,” and finally the more alluring and suspenseful, “The Devil’s Passkey.”

Universal played up what they considered von Stroheim’s perfect credentials for directing such an upscale story set in Paris, a background he had constructed out of thin air. They claimed in Moving Picture Weekly that the director spent time as a young man in the City of Lights, going on to state: “Continental Europe is his birthplace. As an Austrian count he mingled in the most exclusive circles in every capital from Petrograd to London, knowing the gay and fashionable life of every city.”

Another posted for “The Devil’s Passkey.”

The movie’s characters also appeared more decadent and snobbish than those of von Stroheim’s first film, with an added sheen of understated sophistication. Mrs. Goodwright, portrayed by fledgling actress Una Trevalyn, considers selling herself to another man in order to pay off her debts. Relatively inexperienced Clyde Fillmore filled the shoes of blase, breezy American playboy, Rex Strong, who entertains himself in the more lurid pleasures of Paris, playing a role seemingly based on von Stroheim’s typical onscreen playboy personality. Maude George brings a shrewd calculation to her plotting Madame Malot, and Mae Busch brings a flirtatious verve to the vixenish dancer, La Belle Odera. Sam de Grasse brings a respectable gravitas to playwright husband Goodwright.

Luscious, elaborate sets devised by the fastidious von Stroheim mixed with actual stock footage of Paris tricked audiences into believing what they were seeing was actually the cosmopolitan city. Adding a nice, light touch of sophistication, the director played on more adult and humorous portrayals of sexual and romantic relationships, just skirting a tragic ending.

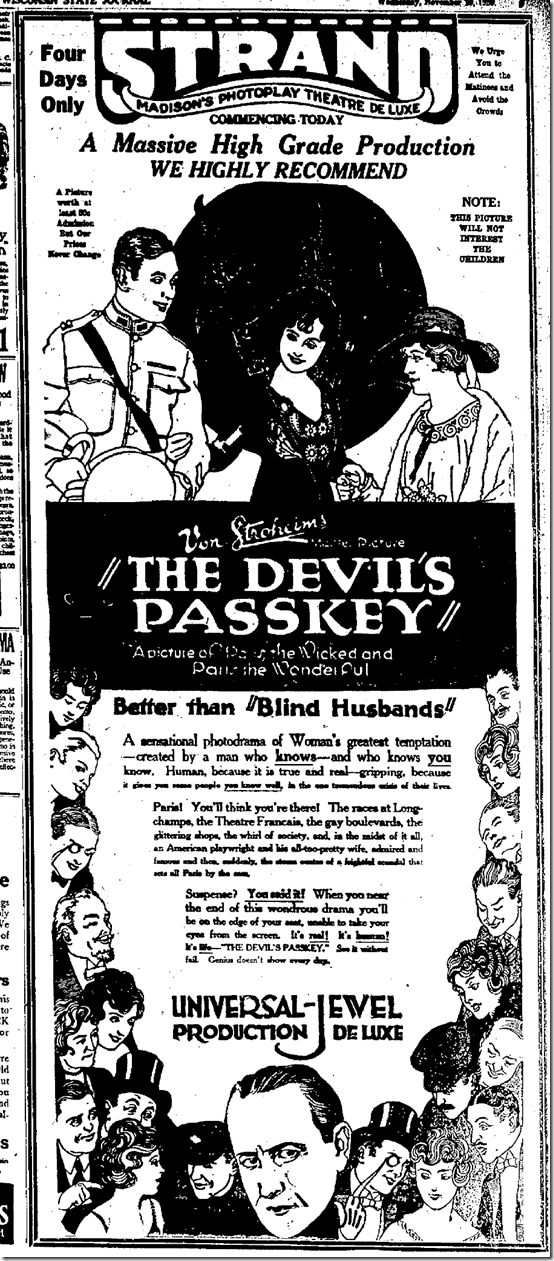

Wisconsin State Journal, Nov. 10, 1920.

The ultimate detail setting the film apart from others was von Stroheim’s focus on story, reproducing it as authentically and faithfully as possible, and making the story plausible through the character’s actions and inner beliefs. As he told the New York Tribune on August 18, 1920, he only directed stories he felt enthusiasm for, and developed endings logical to the story. “But unless I am moved by a story and feel its plausibility myself, I refuse to direct it. I am not trying to give the public what it thinks it wants, but instead seek to give it what I like.”

A few minor points during production should have given the studio notice that von Stroheim refused to play by schedules or rules, foreshadowing things to come. The production required almost two months of filming and Motion Picture Weekly reported that it ended up with over 100,000 feet of film to cut into a regular feature length film of 7,000 feet. The Richmond Times Dispatch stated on February 28 that the director had spent weeks cutting down the film, with Frank Lawrence and his editing crew expected to take two further weeks to get the film to the proper length.

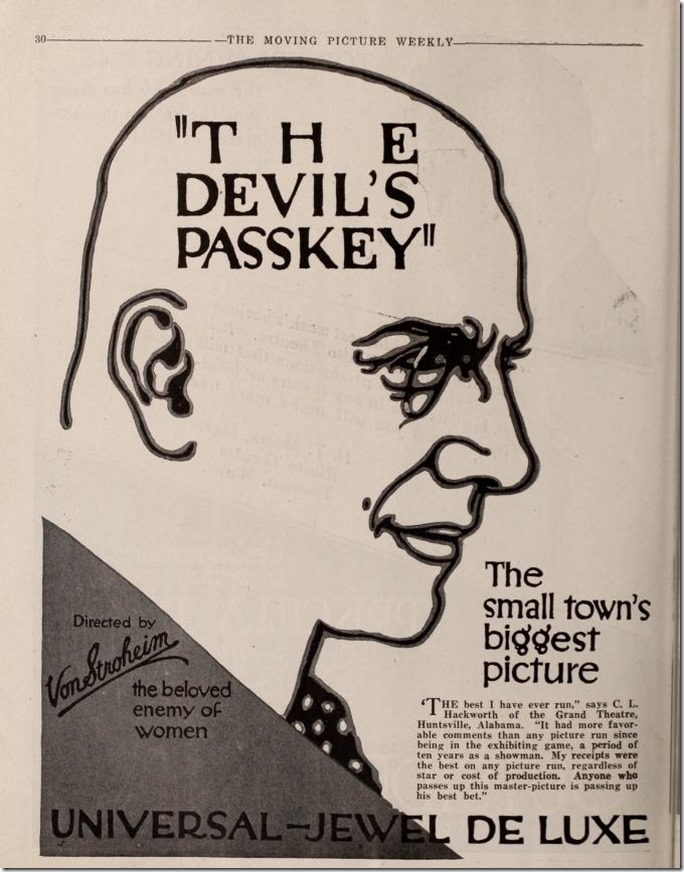

“The Devil’s Passkey” in “Moving Picture Weekly.”

Most probably the studio stepped in to get the film to a more acceptable length for exhibitors, following a April 30, 1920 Variety story which stated that von Stroheim was a one picture man and went on to say, “The thing skidded for the shelf and the director hit the trail east. The final settlement was an agreement on von Stroheim’s part to recut and retitle his picture. This he has done, and it is now announced for release, while the press is anxiously waiting to see if this director is a flash in the pan or the real thing.”

The film’s scrumptious look led Universal to devise a huge publicity campaign pulling out all the stops to promote the film. Twenty three newspaper advertisements were created to appeal to virtually every audience. Some of these ads featured elaborate illustrations, many of which mimicked the elegant and eye-catching five-color lithographic posters (1-sheet, 3-sheets, and 24-sheet). Two two-color teaser posters displaying keys were also produced by the publicity department to help sell the movie. They concocted elaborate lobby displays as well, including one replicating the luxurious tile tub in which Mae Busch soaks.

Many of the film’s ads praised von Stroheim and his more mature style of filmmaking, with one proclaiming it “A Grown Up Picture for Grownups,” and others commenting on the lavish and “pretentious” nature of his film. All played up the adult nature of the film and the moral choices it examined.

Universal began playing up the film’s unique aspects, including its artistic photography, lensed by cameraman Ben Reynolds, with assistance from second cameraman William Daniels. In Exhibitor’s Herald, studio chief Carl Laemmle claimed that von Stroheim created a new process of photography on the film called pastelography, a technique similar to soft focus giving film the appearance of painting.

In its own journal, Motion Picture Weekly, Universal claimed that the film’s use of color through lap-dissolve served as “dramatis personae” in a film for the first time. “The initial experiment in “The Devil’s Passkey” finds the night-long vigil of a repentant woman in the room with her disillusioned and despairing husband. During the cold morning, everything is dark blue. Through the French windows, the dawn is seen to break. A glow grows against the sky, and gradually the sun rises, flooding the room with the hopeful pink of a new day. It is symbolic of what has passed in the minds of the two in that room.”

After a sneak preview, the Studio decided to open the film in the late summer, in order not to compete with “Blind Husbands,” while von Stroheim continued filming his next picture, “Foolish Wives.” They arranged a grand simultaneous opening for “The Devil’s Passkey” in both New York and Chicago for August 8, 1920, with New York’s Capitol Theatre and Chicago’s La Salle Theatre throwing out all the stops.

“The Devil’s Passkey” in “Moving Picture Weekly.”

Almost universal praise greeted the film upon release, with many critics calling “The Devil’s Passkey” even more artistic than “Blind Husbands.” Many remarked on its opulent, sumptuous sets, with one even calling it “voluptuous luxury.” Moving Picture World called it a “sophisticated drama.”

Audiences flocked to see the film, whether in major metropolitan areas or more sedate small towns, setting box office records. Many theaters remarked on their standing room only crowds or extended runs. Perhaps the film’s more moral tone and happy ending helped lure people to screens. This picture was just a little titillating fun, unlike the more outré von Stroheim films to come.

Some played up the adult theme, with an ad in the Wisconsin State Journal November 20, 1920 stating, “This picture will not interest the children,” along with the line, “A sensational photo drama of Woman’s greatest temptation – created by a man who knows – and who knows you know.” The Chattanooga News on October 27, 1920 ran an ad stating, “That’s the finesses of the master director. He knows women – all their luxurious beauty and he thrills you with his knowledge of life.” Motion Picture Classic contained a Universal ad describing his appeal to women as “It’s the ay of the he-vampire.”

“The Devil’s Passkey” in “Motion Picture News.”

Not all loved the film. Los Angeles Times critic Antony Anderson remarked that he had considered von Stroheim an artist with a vital dramatic instinct after seeing “Blind Husbands,” but found this film slightly out of touch and filled with “accidental” touches of art. He called it “miasmatic, it reels with crude and sordid cynicism. This may be Paris, but is a Paris evolved from some hectic Greenwich Village brain, a vision of “modern” life that must have been borrowed from the cheapest of the yellow-backed novels manufactured by the French.” Whatever his views, Los Angeles crowds loved it, leading to a four week run at the Superba Theatre.

Some small theaters saw little box office out of the film, writing in to Exhibitors Herald offering their takes. In the July 16, 1921 issue, R. C. Buxton of the Strand Theatre in Ransom, Kansas commented, “Good picture, but not for small towns, as too deep for most of them. Goes over their heads.” Mrs. N. H. Pfeiffer, manager of the Itasca Theatre in Alice, Texas wrote, “Old hash not browned enough to make it palatable.”

On August 21, 1920, Exhibitors Herald reported that after the success of “Blind Husbands” and the high praise for “The Devil’s Passkey,” Universal had decided to give Erich von Stroheim “carte blanche in his work, regardless of expense.” Little did the studio realize it was unleashing the feverish obsessions and wild ambitions of a hugely talented though undisciplined man, setting up a pattern that would eventually doom the filmmaker to failure.

Unfortunately modern audiences cannot discern for themselves the artistic nature or vision of von Stroheim for “The Devil’s Passkey, “ as it is one of two films he directed that are considered lost. Perhaps one day both it and “The Honeymoon” will be discovered, offering cineastes an opportunity to see the full evolution and growth of an exceptional though unrestrained artist.