Hollywood Heritage will celebrate Marion Davies’ birthday with a celebration Sunday, Jan. 22., at 2 p.m. featuring Lara Gabrielle, author of Marion Davies: Captain of Her Soul, and a showing of Zander the Great. Tickets are $10 for members, $20 for non-members.

Long considered one of silent film’s top comediennes as well as actresses, Marion Davies also ranked as one of Hollywood’s most generous philanthropists. Though never a mother herself, she loved children, be they relatives or those of others, often mothering those in need. After discovering the lack of health resources for destitute families, Davies took it upon herself to establish a clinic to provide medical care for children in Los Angeles.

Born January 3, 1897, in Brooklyn, New York, young Marion Douras charmed everyone she met with her endearing mixture of mischief, humor, and gentleness. After her family experienced downward pressures with the death of her older brother, her father’s alcoholism, and growing financial pressures, the three sisters eventually became showgirls. Marion, the youngest, would find the greatest success, moving on to stardom in motion pictures and establishing a long-term romantic relationship with newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst. Smart in many ways, Marion invested well, and employed her savings in benevolent causes that warmed her heart, especially those dealing with children.

After moving west for her film career, Davies recognized that many experienced financial need though many madly celebrated the roaring jazz age. A group of Westside women met with her in the late 1920s about assisting their cause helping struggling soldiers, farmers, workers, and their families in their clinic as part of the Neighborhood House Association. Originally founded in Chicago in 1897 as Neighborhood House and officially incorporated in 1903 to serve immigrants and those poor in finances and spirit in the district as a type of kindergarten under the name Neighborhood House Association, the group spread across the country, assisting those in need. A group established a cottage in Sawtelle at 1722 Beloit Ave. to help the children of soldiers and farmers and workers who needed care while their parents worked.

Davies gladly donated to the Westside group, remembering the medical hardships of her sister Rose, her own problems with stuttering, and her family’s difficult finances. In 1925, she provided a fully decorated Christmas tree, a meal with all the trimmings for every family, and a new clothing outfit for each child. Davies underwrote the medical services of the Neighborhood House Association in Sawtelle. Her day nursery opened in three rooms of a vacant store in 1926, with the assistance of Dr. Alice Goetz, formerly of the Bureau of Social Hygiene and then the California State Board of Health.

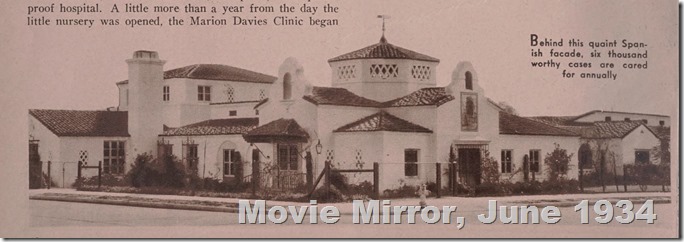

Many quickly came, with Davies realizing that medical services were more greatly needed than a day nursery. She purchased a block of land at 11672 Mississippi Avenue that was formerly the William Lowe dairy on which to build a state-of- the-art clinic. Hiring William Flannery, architect for her Santa Monica Beach house, to design the facility, Davies spent $45,000 in 1928 to construct a gorgeous Spanish Colonial building to serve as clinic to disadvantaged children of Palms, Venice, and Sawtelle. No fees were charged to patients or their families, as doctors worked for free, donating their time. Davies would spend approximately $200,000 to purchase the land, construct the clinic, and fill it with up-to-date equipment.

In 1932, she formally established the Marion Davies Foundation to help operate and finance services. Per Movie Mirror in 1934, “any child living in this territory, up to the age of sixteen years, who needs medical attention of any kind and cannot afford to pay a doctor, may go to the Marion Davies Clinic and receive aid.” Nearly 6,000 children were served for virtually every type of treatment that year, and later almost 12,000 a year received help.

In 1932, she formally established the Marion Davies Foundation to help operate and finance services. Per Movie Mirror in 1934, “any child living in this territory, up to the age of sixteen years, who needs medical attention of any kind and cannot afford to pay a doctor, may go to the Marion Davies Clinic and receive aid.” Nearly 6,000 children were served for virtually every type of treatment that year, and later almost 12,000 a year received help.

Movie Mirror reported that the day began at 6:30 am and children began arriving at 7. Days were set aside for dental, orthopedic, and surgery, with state of the art facilities and tools for each. Children with infantile paralysis could access a small pool identical to the type President Franklin Roosevelt employed at Warm Springs, Georgia. The facility also featured an X-ray room, ultraviolet lamp room, electrical devices, and even a gym. A fifty-bed wing was added to provide hospital accommodation. Families could receive free milk for their children from a delivery service and also obtain visits at home for medical staff.

As an anonymous friend said of Marion in the article, “She has often said the only thing money means to her is the good she can do with it, the happiness she can bring to others. She doesn’t expect any reward and never wants to be thanked for what she does. And she has said many times that she doesn’t consider the clinic charity.” Davies opened her heart to children, giving them opportunities and gifts she felt all deserved, and showing the underprivileged love, respect, and kindness that many never saw from other parts of society. Author Lara Gabrielle, in her biography of Davies, Captain of Her Soul, stated that Davies considered the clinic one of her greatest accomplishments.

Famous friends helped fundraise to maintain the clinic’s high rate of service, from Will Rogers to Mary Pickford to Colleen Moore. Many stars gave money, attended fundraising activities, or even visited. Babe Ruth dropped by the clinic in 1931 to the delight of children. Part of the money raised from visits of Colleen Moore’s doll house in a downtown Los Angeles department store went directly to the clinic as well. Santa Claus even visited children in the clinic’s hospital.

Davies gladly provided medical attention to her “children” as she did her family members, giving from the heart. Her generous nature extended to the military as well. Within a month of Pearl Harbor on January 12, 1942, Davies granted the government use of the facility. All through World War II, the clinic served as the Marion Davies Military Hospital, providing beds for those injured and recuperating from the war.

By the early 1950s, everything had changed in Davies’ life. She retired from the screen in 1938 and her great love Hearst died August 14, 1951. She would marry Horace Brown Jr. less than three months after Hearst’s death. Slowing down, Davies began considering the future of her clinic. At the same time, UCLA began examining the clinic as a possible extension site for its medical school.

Newspapers reported in early June 1952 that UCLA was considering purchasing the Davies clinic after a presentation May 23. Thirty doctors still donated their services one day week per physician and the clinic provided 600-800 outpatient services per month. UCLA was particularly interested in maintaining the operating room and providing services to more additional clients than they could hold at their main hospital.

On November 6, 1952, the UCLA School of Medicine officially assumed control of the Marion Davies clinic, with their pediatrics and hospital administration operating the facility together. They announced they would also continue to open weekdays from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. to all Los Angeles children in financial need. UCLA extended service to those suffering muscular dystrophy and neurological conditions. The clinic would also serve as a research and training facility for the school.

The Marion Davies Foundation announced July 2, 1957 that it would dissolve assets and transfer $1.5 million to the construction of a wing at UCLA Health Center dedicated to the clinic and designed by Capitol Records architect Welton Becket. UCLA commenced construction in fall 1960 after an over $2-million gift from Davies and over $500,000 from the United States Public Health Services for research quarters in the building.

The 68,000-square-foot building would possess four floors, two above ground and two below, and allow for future construction of a six story building. Facilities would include an outpatient clinic with 31 examining rooms, indoor and outdoor playing areas, a conference room, dental clinic, research laboratory, offices, and lecture room. Sadly, it would not open until after Davies’ death. The Marion Davies Children’s Clinic still exists today as part of UCLA Health Center.

Selfless when it came to helping needy and disabled children, Marion Davies generously provided to build a beautiful children’s clinic, and later contributed to its continuation at UCLA. Her sweet spirit of kindness still survives, acknowledging a gift for which she is little known.