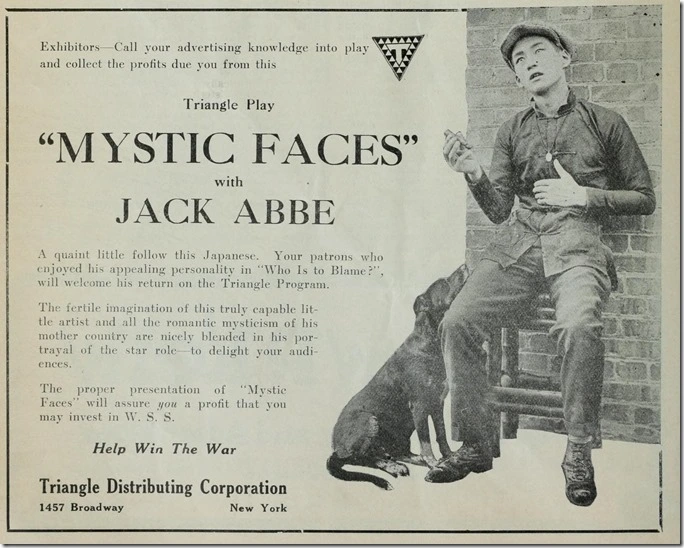

Jack (Yutaka) Abe in an ad for Mystic Faces in Film Daily, Sept. 1, 1918.

Virtually unknown today, young Yutaka Abe gained fame in the American silent film industry after immigrating to the United States in 1912. While not as successful as fellow Japanese immigrant Sessue Hayakawa, Abe received excellent reviews for his film work, even writing for the screen. When the country became increasingly intolerant in the early 1920s and added Japanese immigrants to the harsh dictates of the Exclusion Act, originally written to handcuff the Chinese in the United States, Abe returned to his home country, becoming a successful director.

Born February 2, 1895, in Yamato, Miyagi, district, Abe and his younger brother, Toshinaka, immigrated to the United States with their father from Japan’s Sensai district, arriving in San Francisco on June 3, 1912. Later newspapers would claim that he was the son of the renowned Japanese ship builder. They arrived the year before California passed an alien land bill against the Japanese in 1913, preventing them from purchasing land or working certain professions.

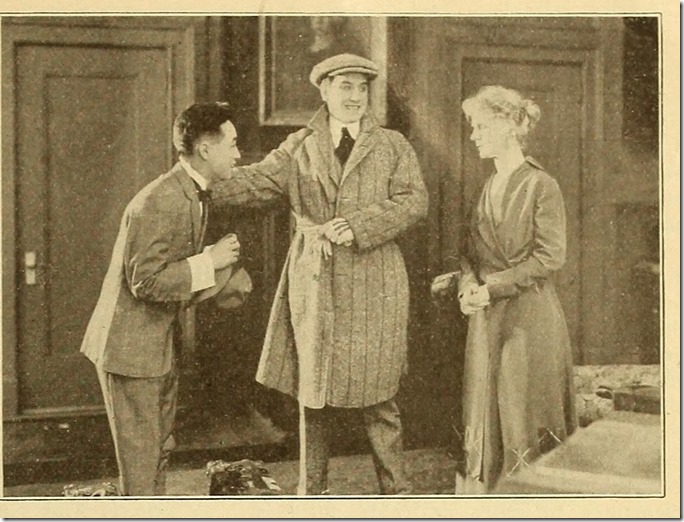

Jack Livingston and Jack Abe in Who Is to Blame?

It appears the family arrived in Los Angeles in late 1914 or early 1915, where perhaps the young man joined Tsuru Aoki’s acting troupe in downtown Los Angeles. It appears that Abe first appeared on film in a small role as a Japanese servant in Cecil B. DeMille’s 1915 film The Cheat starring Hayakawa, as some newspaper stories credit him in the cast under the name Utaka Abe. Abe would later state that he appeared in two short Japanese films before his feature debut.

Abe and his family would have endured somewhat difficult conditions before the young man found employment in the entertainment industry. As SurveyLA’s “Japanese-Americans in Los Angeles, 1869-1970,” study states, most male Japanese immigrants first lived in boarding houses run by day work employment agencies around and near downtown Los Angeles after arriving, mostly in segregated districts. Many found menial positions working in laundry, gardening, and restaurants while looking to gain better positions and living conditions. For virtually all of his time in Los Angeles, Abe does not appear in city directories, leaving no record where he resided. There is also no record if he married or not, since there was a deficit of women to men at the time. Japanese men were forced to marry what were called “picture brides,” after seeing photos of young Japanese women willing to marry and move to the United States.

Abe begins to gain notice in late 1917 stories about Triangle films with an Asian theme for Thomas Ince under the name “Jack Abbe,” perhaps as a way to appeal to white audiences. In late January 1918, the film originally entitled M. Butterfly but now called Her American Husband, appeared in theatres to tepid reviews. Cast members Thomas Kurihara, Misao Seki, and Abbe, all members of the Japanese Photoplay Association of Los Angeles, hosted the cast and crew at a leading Japanese restaurant downtown.

Jack Livingston and Jack Abe in Who Is to Blame?

The now “Jack Abbe” received mostly excellent reviews for his supporting roles, large for a person of color. He often appeared as a major supporting player helping more the story along. In the Frank Borzage directed film, Who Is To Blame? Abbe played a rickshaw boy brought to the United States by an American to serve as his valet. As most actors of color at the time, he sacrifices his success to be honorable and save the day. Exhibitors Herald trumpeted his work, stating, “Worthy of the highest praise is the work of Jack Abbe, whose winning smile and inimitable mannerisms make a lasting impression.” Motion Picture News described him as a Japanese Jack Pickford because of his appealing personality.

Ambitious and creative, the young man co-wrote the script for his next film, Mystic Faces, starring in the pro-WWI war as well. For once, an Asian takes action while also achieving success of his own. In the film, Abbe’s character delivers packages for his uncle’s antiques shop while also befriending an American couple. When the Red Cross nurse is abducted by German spies, Abbe goes undercover and rescues the woman, thus gaining a large reward to marry his Japanese sweetheart. Advertising featured Asian themes and even showed the couple eating food with chopsticks, while calling him “quaint little fellow”. The studio’s press materials suggested theatre managers “play up the star” because of Abbe’s fine acting and charming persona. Many trade papers thought that if studios cultivated Abbe and his talent, a new star would be born.

Abbe next appeared in The Tong Man, produced by Hayakawa’s own company, Haworth Pictures, and starring the leading actor. While the film included a mostly Japanese or Asian cast but playing Chinese, it featured many stereootypical type Asian characters and themes, with Hayakawa playing an assassin for a tong skilled in using a hatchet, whose girlfriend is the daughter of an opium dealer. Abbe and Hayakawa hit if off, with the more established actor serving as a mentor for the younger man. Hayakawa would give him access to his company to study the production process, a great learning opportunity for the driven young man.

Inspired by his acting, diva Alla Nazimova signed Abbe for her film The Red Lantern, in which she would star as a Eurasian. Working with writer June Mathis, Nazimova shaped the role of the Dowager Empress for Abbe, his only drag performance but a serious one. The New York Tribune praised him, stating, “Aided by a wig, some clever makeup and the elaborate embroidered robes of state, he gives a remarkable impersonation of the crafty and treacherous ruler of the Chinese Empire during the turbulent days of the Boxer uprising of 1900… .”

In his next film, Abbe once again received excellent reviews, for a film we would consider problematic now, featuring H.B. Warner sent by the United States government to “quell a Chinese rebellion.” He is almost seduced by a Chinese vamp and has to save his American girlfriend and her father from what the studio called a gang of “chinks.” Wid’s Daily called Abbe’s work second only to that of Warner, calling it “Here was a piece of serious acting that was well executed.”

For the 1920 film The Willow Tree, Abbe served as a technical advisor, providing screenwriter June Mathis “details of the home life and customs of the Japanese” per various trades. While his role was not as large in this film, his research work played a major role, as he also worked with Japanese children extras and suggested costuming to lead actress Viola Dana.

By 1920, Hayakawa played a major part in Abbe’s life as mentor. The Motion Picture Studio Directory lists Abbe as living at the Hayakawa home. Abbe himself was also acting in Tsuru Aoki films at Universal. Perhaps the two were also giving the young man pointers on how to live with the restrictive state policies as well as the subtle and not so subtle racism they experienced every day.

Abbe’s penultimate American film, Lotus Blossom, was released in late 1921 and produced by the Wah Ming Motion Picture Co. at the Leong But Jung Productions studio in Boyle Heights. Co-director and writer, Chinese born James B. Leong, established his company through financing by Chinese businessmen to produce Chinese stories with Chinese actors. Perhaps the only film the company produced, Lotus Blossom starred Lady Tsen Mei as the female lead, a young Chinese American woman who possessed college degrees in medicine and law, besides singing and playing the piano. To help sell the film to American audiences, Tully Marshall and Noah Beery also starred. Abbe found inspiration in the film, sealing his decision to focus on directing and writing rather than appearing in front of the camera.

With policies further repressing the lives and rights of Japanese and Japanese Americans, Abbe decided to return to a more free and open life in Japan in either 1922 or 1923. Newspapers reported Abe returned to Hollywood in 1925 to observe Frank Borzage directing The Circle at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer before going back to direct. He hoped that Japanese films could eventually dominate their own box office, instead of seeing American films push out native films. He told Exhibitors Trade Review that Japan offered him the most opportunity and freedom as a director, especially thanks to his schooling and experience in American film production.

Thanks to careful observation while working on films, Abe became known as the “DeMille of Japan,”employing Hollywood conventions and techniques to update Japanese cinema. He later became known for excluding details not necessary for forwarding the story to focus solely on action and composition. During World War II, Abe turned out propaganda films as did many in Japan. By the time he retired, Abe had directed 72 films in Japan for major companies like Nikkatsu and Toho. When he died in Kyoto in early 1977, renowned director Akira Kurosawa helped plan his funeral.

While unable to fulfill his ambitions and talents in the United States, Abe gained his full renown and respect as a film director in his native Japan, without feeling the racism and rejection of Exclusion Act policies in California. While he enjoyed freedom in Japan, his brother Toshinaka had remained in Los Angeles and worked in small roles as an actor, continuing to live in a downtown boarding house. Records show that he was rounded up in early 1942, and sent to Santa Anita Racetrack before shipped off to an internment camp.

Many Japanese actors contributed to the early American silent film industry but found their contributions virtually erased from history. Hopefully more can be found on these men and women and give them the recognition they deserve. Abe should be recognized for his talents and skills in America, that he only fully developed after returning to his native Japan.