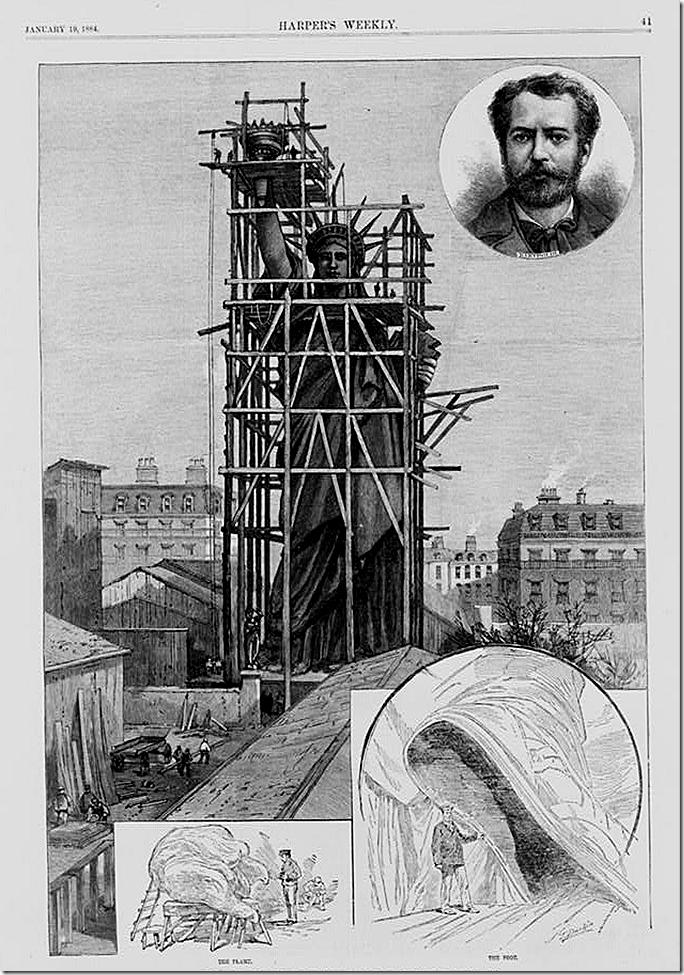

Construction of the Statue of Liberty, artwork by John Durkin, Harper’s Weekly, Jan. 19, 1884.

Written in 1883 to help raise money for building the pedestal on which the Statue of Liberty would stand, Emma Lazarus’ 14-line poem “The New Colossus” would take on a life of its own: becoming enshrined on the statue as a memorial to the poet and as a statement of welcome to those seeking refuge in our country. As we approach Independence Day, the meaning behind its words rings even clearer today.

Born July 22, 1849, in New York City as the fourth of seven children to wealthy merchant Moses Lazarus, Emma received a strong private education, learning to speak at least four languages and becoming an excellent writer, especially in poetry. Ralph Waldo Emerson mentored her. She translated works of literature as well as setting down her own odes, many based on romantic literature and others on troubling historic events regarding her fellow Jews, receiving much praise upon their publication. She also worked to alleviate the suffering of women and the poor.

Mary Mallory’s “Living With Grace” is now on sale.

A Statue of Liberty ashtray dated 1947, listed on EBay at $12.99.

By 1881, Miss Lazarus directed her attentions to relieving the suffering of Jewish refugees fleeing czarist Russia pogroms by escaping to New York City. She tutored unskilled immigrants and taught them English, devastated by their oppressive and horrific past, working to help them escape poverty, hunger, and suffering and becoming an observant Jew herself in the process. Mary M. Cohan believed that Lazarus’ soul was dedicated to aiding the oppressed and homeless.

During this same period, French intellectuals began advocating for the creation of a statue celebrating Liberty to give the United States in honor of its Centennial. Sculptor Auguste Bartholdi began work in 1870 on designing the monumental work called “Liberty Enlightening the World” that Gustave Eiffel would build and which still stands today. Bartholdi himself saw it welcoming those in need and escaping tragic circumstances, believing its spirit “a personification of hospitality to all great ideas and to all sufferings,” per the book “Enlightening the World: the Creation of the Statue of Liberty.”

Eiffel completed the head and torch-bearing arm long before the statue was fully designed and completed. They were exhibited at exhibitions around the world like the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876 and Madison Square Park from 1876 to 1882 as the statue was completed in France. In America, however, fundraising lagged on its part of the statue, the pedestal.

United States’ fundraising for the statue’s pedestal began in earnest in 1882, with the Bartholdi Pedestal Fund established in 1883. Donations sagged, however, so writer Constance Cary Harrison helped organize an Art Loan Fundraising Exhibition that December to help augment the fund. She compiled writings and sketches to be displayed and/or auctioned on the evening of Dec. 6, 1883, pressing Lazarus to compose a poem for the event. Per “Enlightening the World,” Harrison begged Lazarus in a letter to write something by telling her, “Think of that Goddess standing on her pedestal down yonder in the bay, and holding her torch out to those Russian refugees of yours . . .”

Harrison’s strong words worked, and Lazarus completed a poem read at the gala opening of the exhibit on Dec. 3, 1883, unlike other works by such people as Mark Twain or Walt Whitman. The Dec. 4, 1883 New York Times reported that Lazarus’ work was the only one read at the event:

“Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land.

Here at our sea washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning and her name

Mother of exiles. From her beacon hand

Glows worldwide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

‘Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!’ cries she,

With silent lips. ‘Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest tossed, to me!

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!’”

From her days working with frightened Jews from Russia looking for safety and nurture, Lazarus saw America and the statue which it represented as a true Mother of exiles, a welcoming sanctuary offering haven for the homeless, hopeless, hungry, and hurting.

From her days working with frightened Jews from Russia looking for safety and nurture, Lazarus saw America and the statue which it represented as a true Mother of exiles, a welcoming sanctuary offering haven for the homeless, hopeless, hungry, and hurting.

The press and many others praised the poem. Poet James Russell Lowell wrote Lazarus personally that her work had given the statue a “raison d’etre.” Art Amateur magazine published it soon thereafter, and waves of support grew for both it and refugees. In 1885, orator Chauncey M. Depew declared at the Bartholdi reception, “The statue would for all time to come welcome the incoming stranger.” President Grover Cleveland avowed that Liberty’s light would “pierce the darkness of man’s ignorance and oppression” until Liberty enlightened the world.

In 1887, Lazarus died of cancer and the poem seemed forgotten, though Ellis Island was constructed nearby in 1892 to welcome and receive immigrants taking to heart the message of the poet’s ode. Georgina Schuyler rescued the poem in 1901 when she worked to memorialize Lazarus by seeing it inscribed on a bronze tablet and placed inside the statue’s pedestal.

A dedication ceremony for the plaque bearing the last five lines of Lazarus’ poem was held May 6, 1903. The New York Times and Tribune covered the unveiling, with the Tribune calling Lazarus “the most talented woman the Jewish race has produced in this country,” dedicated to helping “persecuted and exiled Jews.” The New York Times wrote, “The choice of this plaque rests on the interest which Emma Lazarus took in the Liberty Statue as a symbol for a land where the down-trodden and despised have found a chance to develop their own careers… .” The Aug. 30, 1903 Los Angeles Herald wrote that “…her wider sympathy with all human suffering and oppression seeking relief in coming to our shores, and her faith in American ideals and institutions” was expressed in her work.

Over the next century, newspapers would quote the poem in Fourth of July editions and several books would examine both Lazarus and her poem’s connection with the Statue of Liberty, with the Jan. 13, 1918, New York Tribune calling her words “the credo of American democracy.” On the 50th anniversary of the statue’s dedication, President Franklin D. Roosevelt recognized the truth of Lazarus’ words in his speech, noting that “…a steady stream of men, women, and children followed the beacon of liberty” to the United States. “They brought us strength and moral fiber, developed in a civilization centuries old but fired anew by the dream of a better life in America. They brought to one new country the cultures of a hundred old ones…Here they found life because here there was freedom to live.” His words described our country, a nation of Native Americans born here and a huge population composed of refugees and immigrants from other places and cultures, a giant melting pot of freedom-seeking humanity.

Author Louis Adamic discussed Lazarus’ “The New Colossus” in his article “Our Country” published in papers like the Sept. 12, 1940, Dunkirk Evening Observer, describing the credo of America as defined by the poem. “Americanism, as I see it, is a movement away from primitive racism, fear and nationalism, herd instincts and mentality and superiority, and snobbery; a movement toward freedom, creativeness, a universal or pan-human culture.”

The Syracuse Herald Journal on June 30, 1948, spoke to the moral and spiritual truths of Lazarus’ words as well, saying, “Americans too often are prone to take their liberties for granted,” calling attention to the Statue of Liberty, ‘a symbol of freedom and justice, not only to the people of America but to the oppressed, homeless peoples of the world.”

After surviving World War II and its horrors, many writers and composers also recognized the wisdom of Lazarus’ poem. Gordon Jenkins, musical director of Decca, employed the last sentences of the work in the top-selling “Manhattan Tower” composition. The legendary composer Irving Berlin also admired Lazarus’ stanza, adapting the same lines as lyrics for the final number in his 1949 musical “Miss Liberty,” celebrating the statue’s creation and how it represented America and its values.

A playbill for Irving Berlin’s “Miss Liberty,” listed on Ebay for $5.99.

Production team Robert E. Sherwood, director Moss Hart, and choreographer Jerome Robbins worked with Berlin to honor America and its values of freedom and democracy for all. Variety’s June 15, 1949 review reported that the grand finale of “Give Me Your Tired, Your Poor” featured all the principals and chorus “joining in a rousing ensemble honoring our country’s principles of tolerance and liberty.”

Patriot that he was, Berlin donated all copyright proceeds of the song “Give Me Your Tired, Your Poor” to the Boy Scout Foundation Fund, assigning himself a high royalty rate to ensure nice profits for the Fund. At the same time that fall, Fred Waring’s Pennsylvanians released an album featuring the song.

Lazarus’ stirring words led many organizations to employ them when saluting America and its values. New York’s Idlewild Airport employed most of the words in the last five lines of the poem when it was engraved there in the 1950s, save for excising the words “Wretched refuse.” “The New Colossus” was quoted during National Brotherhood Week in the 1950s for National Unity Day.

During the June 28, 1959, National Unity Day celebration, Gen. David Sarnoff declared that immigrants not only took from America but gave something even greater in return, their time, talents, respect, and undying loyalty. “…We are lucky in this country. But just being lucky doesn’t make us better than anyone, it just makes us luckier…Immigrants “…brought with them great gifts – the brains and the brawn that are cemented into America’s highways and roadways, skyscrapers and farmhouses, mines and factories, from shore to shore. They brought with them the hungers for human freedom, individual dignity and self-improvement that are at the heart of the American Dream…For it is the unique glory of our country that it neither demands nor imposes an artificial uniformity. Our strength lies in unity…America is less an amalgam than an integrated mosaic.”

As we celebrate the upcoming Independence Day, let us remember Lazarus’ poignant and thoughtful words and how they welcomed past generations of our ancestors to this country escaping violence, misery, hunger, and despotism in search of peace, justice, and freedom for themselves and their future generations.

.

Sadly, we have most recently lost our right to that amazing gift from France. That magnificent Statue now shows us how much we have traded our values for the illusion of security.

LikeLike