Jan. 6, 1924: The Times publishes a photo of an Oakland car that was driven up to the Hollywood sign.

In the early 1920s, developers began opening virgin tracts of land for construction all around Los Angeles. To help sell these new developments, real estate agents coined fancy names like Bryn Mawr, Outpost Estates and Whitley Heights, while also constructing large signs spelling out their names with individual letters in white and red.

The Beachwood Canyon development named Hollywoodland opened March 31, 1923, under the auspices of real estate developers Tracy Shoults and S. H. Woodruff, on behalf of landowners E. H. Clark and Moses Sherman, and partner Harry Chandler. They considered the best way to advertise their new planned community, as well as outshine the myriad other developments around the city.

Mary Mallory’s “Hollywoodland: Tales Lost and Found” is available for the Kindle.

Hollywood Leaves, Nov. 16, 1923.

Only four months after breaking ground, however, lead developer Shoults died. The company quickly regrouped under Woodruff’s leadership, but Shoults’ name remained in the top position in advertising for more than a year before being removed, so respected was his name. Back on steady ground, the partners considered how best to promote their luxurious development, besides all the free advertising Chandler threw their way in his Los Angeles Times.

According to advertising man John Roche, he was hired by Chandler to design a sign that would be visible from Wilshire Boulevard. He sketched out the word “Hollywoodland” on a sheet of paper, but went the other spelled signs one better: he supersized the letters. Roche drew large, white letters to stand 50 feet high and 30 feet wide, much larger than all the other signs.

The sign was constructed in the second half of November 1923, per evidence discovered this summer.

No newspapers or books from the period contain stories or photos of the Hollywoodland sign from 1923, save the Los Angeles Times, which contained a Dec. 30, 1923, story recounting how an Oakland Motor car ascended to the Hollywoodland electric sign, and displayed a photo of the car below the sign on Jan. 6, 1924.

Newsreel outtakes do show construction of the Hollywoodland sign, as men and tractors drag material up the hill, and workers wave from the letter “H.” I consulted Greg Wilsbacher, director of the Fox Movietone Newsreel Collection at the University of South Carolina, to see what the records pertaining to this footage say about when it was shot or delivered to Fox.

Wilsbacher informed me that records state that the Fox Movietone New York office received the undeveloped footage from their Los Angeles cameraman, Blaine Walker, “November 27th–23.” The punch record created by the office after the film was developed also dates to late November 1923. Although Walker could have shot the footage months earlier, his job as Fox’s Los Angeles newsreel photographer was to capture and send newsworthy footage to New York as soon as possible for exclusives.

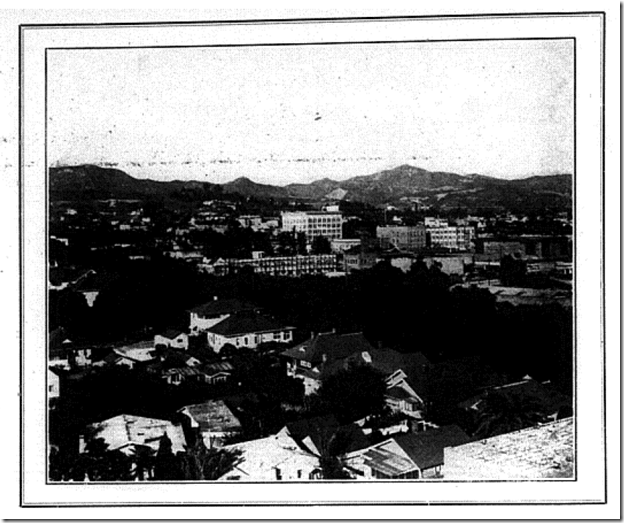

From further research, I discovered this somewhat grainy image in the Nov. 16, 1923, Hollywood newspaper, Holly Leaves, displaying a photograph of the Hollywood Hills visible from the tower of the Hollywood Athletic Club. No Hollywoodland sign appears on the hillside.

No one considered the Hollywoodland sign out of the ordinary in 1923, as several other similar billboards stood around the Los Angeles area, all dwarfed in size by the new sign. In fact, the Hollywoodland sign fails to appear in the newspaper again until Sept. 18, 1932, when all area papers trumpeted the sad news of actress Lillian “Peg” Entwistle’s suicide leap from the sign.

The Hollywoodland sign again disappeared from the papers, only to pop up again in the 1940s as parts of it fell off, caught fire or blew away. The M. H. Sherman Co. turned the sign over to Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks in 1945, which wanted to destroy it in 1949, rather than repair it when the “H” blew away in a storm. Residents madly protested, declaring it a landmark in letters to the editor and city hearings. The Hollywood Chamber of Commerce took over ownership of the Hollywoodland sign at that time, removing the word “land” so that it could advertise the city of Hollywood.

Ironically, a billboard thrown up quickly and haphazardly in1923 soon became an advertising emblem employed by the chamber to promote Hollywood as both a city and film industry. From that point on, the Hollywood sign grew in popularity. While it had made cameo appearances in feature films and cartoons since the 1930s, it played its first major role in the 1954 film noir drama “Down Three Dark Streets.”

The Hollywood sign now ranks as the city of Los Angeles’ top tourist attraction, a mecca for worldwide visitors thanks to its many film and television appearances. For many, the Hollywood sign is now a world wonder, as iconic to the landscape as the pyramids and Sphinx in Egypt and the Eiffel Tower in Paris.

A very creepy tidbit from James Zeruk’s new biography of Peg Entwistle notes that the letters were trucked uphill RIGHT PAST HER HOUSE on the way to to their construction site.

LikeLike

That poor girl. Am I remembering correctly that she didn’t die immediately, according to the M.E.? A particularly painful death, I’d think. If only she’d known a part was awaiting her…didn’t it arrive by mail, too late? I think the only thing I’ve seen Miss Entwhistle in was that film where Myrna Loy was playing a half-caste villain. Sad.

LikeLike

The “LAND” part of the sign was destroyed in the movie THE ROCKETEER. I believe it was wiped out by movie star/Nazi spy Neville St. Clair, a doppleganger for Errol Flynn, when his stolen rocket backpack malfunctioned. Or was it the exploding Nazi zeppelin?

LikeLike