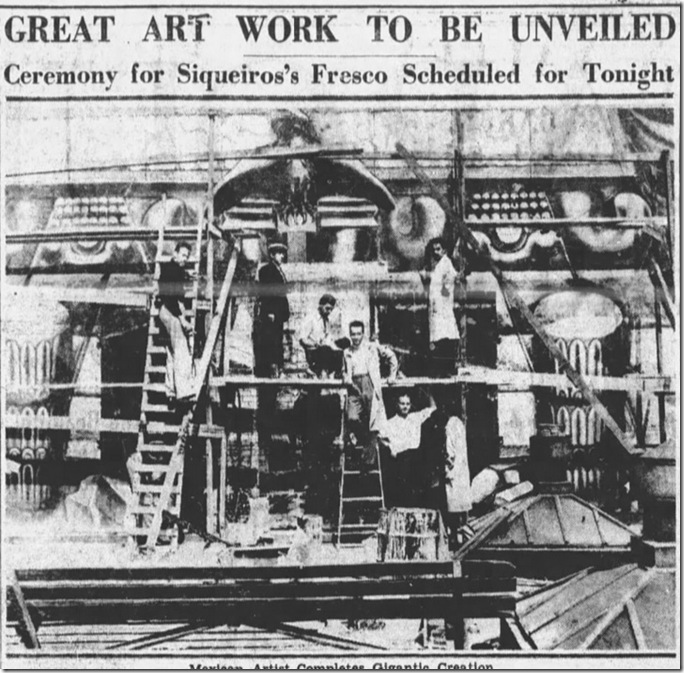

America Tropical, Los Angeles Times, October 9, 1932.

F. K. Ferenz of the Plaza Art Gallery at Los Angeles’ El Pueblo looked to make a statement in 1932, showing that the city celebrated world class artists and Olvera Street was the place to visit, when he commissioned world renowned Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros to create a mural on the upper wall of his gallery. Audacious and bold, the work of art called out the American government at a time when the country sunk deeper into the Great Depression. Its story of censorship and retribution speaks out even today.

Virtually forgotten by the city, Olvera Street and El Pueblo saw rebirth thanks to the efforts of Northern California native Christine Sterling. Dismayed that city officials ignored the care and upkeep of the very place where the city of Los Angeles was founded, she led a crusade in the late 1920s to save it and the area’s first home, the Avila Adobe. Organizing a letter writing campaign and winning donations to restore the Adobe, she finally convinced the city to restore and update the street into a romanticized “Spanish atmosphere” and marketplace.

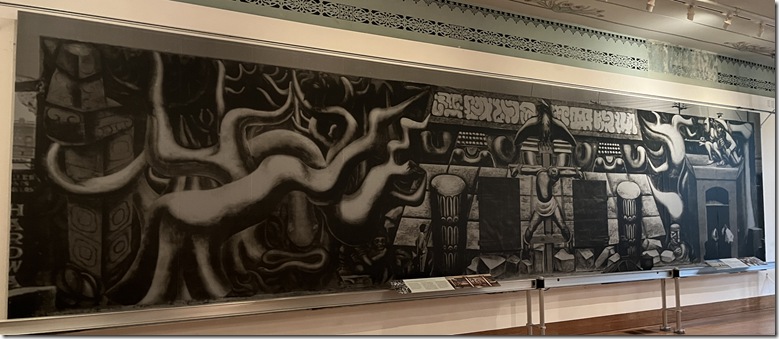

America Tropical Interpretive Center Interior Photo by Natecation, from Wikipedia.

Visionary Siqueiros found Los Angeles a place of refuge in the spring of 1932 after his own country deported him for speaking out against oppression. An avowed leftist, Siqueiros advocated for social change and equality. He considered himself a “soldier artist,” attempting to awaken the public to the fight against injustice, especially in al fresco work freely visible to all.

Looking to make a statement, Chouinard School of Art hired the artist to teach mural painting to the school’s and city’s students. Such artists as Millard Sheets, Donald Graham, and Tom Beggs, director of art at Pomona College joined with others to “learn something of the technique for which he is famous,” per Sheets, as they considered fresco painting, virtually forgotten for 400 years, the appropriate art for Southern California’s concrete buildings. Little did Siqueiros realize that the artistic process of producing the piece would foreshadow his work at Olvera Street.

For more than two weeks in late June, the artists worked on the twenty-five foot mural designed by Siqueiros for one wall on the school building. Unveiled to the public on July 7, the work featured laborers of multiple ethnicities as well as an African American man holding a light skinned child and a white woman holding a child of color. The work was eventually whitewashed, with multiple reasons given for its destruction over the years.

The prolific Siqueiros employed his time wisely, not only teaching students but also finding time to create art, lecture on its creation, as well as to join with others in fighting for better living conditions. He lectured at art clubs like the California Art Club around the city, created paintings and lithographs displayed at Stendahl Art Gallery, and discussed social change, capitalism, and workers’ rights with members of the John Reed Club. He also served on the jury of muralists judging works to be exhibited during the upcoming Summer Olympics in Los Angeles.

The prolific Siqueiros employed his time wisely, not only teaching students but also finding time to create art, lecture on its creation, as well as to join with others in fighting for better living conditions. He lectured at art clubs like the California Art Club around the city, created paintings and lithographs displayed at Stendahl Art Gallery, and discussed social change, capitalism, and workers’ rights with members of the John Reed Club. He also served on the jury of muralists judging works to be exhibited during the upcoming Summer Olympics in Los Angeles.

Realizing the draw a Siqueiros’ work would bring to his gallery during the Olympics and beyond, Ferenz commissioned the artist in August to design and complete a monumental work with the title “America Tropical or “Tropical Mexico” as some reported, to fill the eighteen feet high by eighty feet long wall of the second story south wall of the building, the former Italian Hall. Sterling most likely approved the mural addition to the restored El Pueblo in order to draw customers to the fledgling entrepreneurs. Dean Cornwell, artist of the Los Angeles Central Library’s rotunda mural, sponsored the work and also joined as one of the participants.

The Los Angeles Times reported that the fresco would “represent the tropical section of Mexico where sugar is produced,” with such artists, decorators, film designers, and painters as Peter Ballbusch, Jacob Assanger, and Luis Arenal to assist in its creation. While Siqueiros himself designed the art, the twenty one assistants would provide the outline with the artist finishing the work. In fact, it could be called the first example of graffiti art in the United States, as the mural would adorn a concrete building with a message for the general population, with color applied mostly by air guns and brushes.

Working at night under electric light, Siqueiros employed Portland cement rather than plaster as the work’s base, using water color paint to finish the design of a Mexican tropical jungle, which the Times noted, “About a ruined Indian temple will rise huge trees in which parrots lodge. Pumas and reptiles will be in the forest and Indians will form colorful notes amid the green foliage.”

Even before the mural’s unveiling, Siqueiros faced removal from the country. As he looked to extend his visitor’s visa to the United States, hypocritical government officials considered revoking it for “alleged radical remarks and ideas” he had made. Ironically, the government had understood his leftist ideas when granting the original permit, as newspapers around the world acknowledged his leftist politics and support of socialist causes. The artist himself did not want to return to Mexico, but instead go to South America through New York City to complete some commissions.

On the night of October 8, Siqueiros sent the bloc of muralists away to complete his last figure, a dying Indian crucified and lashed to a cross before the October 9 unveiling. At 8:30 pm that night under misting rain, Ferenz served as master of ceremonies for the grand opening of what was called the largest mural on the continent. The large crowd gasped at the dramatic work’s unveiling, visible for what was described as miles under blaring electrical lights. Many were shocked to see the central figure of the crucified native, while others recognized the power and majesty in the art.

Don Ryan of the Los Angeles Daily News, praised the work’s monumentality. “Flaring in the night, the Siqueiros fresco seems to be embedded in the sky above Olvera Street…Before the puny hurrying figures on the roof the heroic creatures on the wall preserve their tensile calm. The central figure is a man crucified. Above his head is an eagle perched, around him the sap driven jungle breaks apart the ruins of old civilizations, and up in the furthest corner two snipers of the future creep stealthily into the picture.” He stated that Siqueiros declared “that buildings of the future are going to be covered with these dynamic paintings so peculiarly the product of communism in art, of groups working together with a single aim.”

LA Times art critic Arthur Miller praised it as well, acknowledging that ‘the country should welcome a man who works with such sincerity and talent, who shares so unselfishly with others his valuable technical and artistic knowledge, and who aids our artists to develop the art of direct wall painting… . Powerful is a tame word for the forms he created…It is a Mexican’s picture of his own troubled land, Siqueiros’ picture of the tragedy of history and of man’s fate. The human sacrifice lies deep in the heart of the old races of Mexico. Interpret it any way you like, it is a work that first arrests and then holds the mind through the strength and simplicity of its forms and the art of their organization into a design.

In the midst of our popular conception of Mexico as a land of eternal dancing, gayety and light-headedness, this stern, strong, tragic work unrolls its painted cement surface. The Greeks, too were gay but their dramatists aimed to inspire ‘pity and terror.’ One remembers Greek tragedy looking at this second outdoor fresco by David Alfaro Siqueiros – an artist whose intelligence, sincerity and courtesy have made him hosts of friends during his stay in Los Angeles.”

Siqueiros himself described the work in his unpublished memoirs. “It is a violent symbol of the Indian peon of feudal America doubly crucified by the oppressor, in turn, native exploitative classes and imperialism. It is the living symbol of the destruction of part national American cultures by the invaders of yesterday and today.”

Ryan reported on the blood thirsty lust of many wanting to deport the artist for simply being “a dangerous red” and disagreeing with main government policy. Academic freedom and free speech was under threat, as Leo Gallagher, L.L.D. and formerly of Northwestern University’s faculty, told the John Reed Club of his dismissal from the college merely for appearing as attorney in court for some people arrested for what was called “radical activities.” At a time when the Hoover government approved the Smoot-Hawley Tariffs against foreign powers and saw its greedy policies lead to hunger and homelessness, they denigrated work celebrating diverse people uniting together to right injustice and improve living conditions. Siqueiros revealed the significance of his work in the fight for society and inequality when he lectured on “The Social Importance of the Fresco Painting” at the Plaza Art Center on October 28.

On November 11, the United States government deported Siqueiros from the country for what they considered “subversive” speech. Losing out on his East Coast commissions, the artist traveled on to South America before heading to Europe.

Olvera Street and El Pueblo also considered the mural more than they had bargained for. Within months, offended officials whitewashed the revolutionaries out of the work, but no one knows by whose permission. Censoring the artist’s work even further, the mural was completely painted over within the decade, hiding a message that some considered radical, that the United States government exploited its own residents much less those of foreign countries.

Over 50 years, the wall containing the mural remained a white eyesore, though many called for the work’s restoration. Finally in 1987, the Getty Conservation Institute stepped forward to remove what white paint still obscured the art and to stabilize the image as the paint and sun over the years had severely damaged much of the work. They created special covers to protect the mural from both the sun and weather elements like rain to preserve its life as long as possible, as complete restoration was impossible without original color images of the mega work.

Opening to the public in 2012 as part of the America Tropical Interpretive Center, the mural can be visited to this day during opening hours of the museum. Though now somewhat faded, the art’s visceral message and power still attract attention with its dynamic hold on viewers. The work’s saving and resurrection demonstrate the mural’s dramatic impact on both the culture and life of Los Angeles, documenting the importance of free speech and speaking out against injustice.