Later, friends and relatives would recount the episode and shake

their heads. It wasn’t just the naivete. By the time she married him

seven years later at the age of 25, it seemed there had never been a

time when the larger-than-life celebrity had not dominated her

existence.

Their home was his mansion. Their friends were his friends. Her

relatives were his employees. When she decided to take up interior

decorating, her only clients were Simpson and his pals. Friends said

that if he did not like what she was wearing, she would change clothes

to please him. Later she would tell friends that she felt so

overwhelmed, not even her words felt to her like her own. In a divorce

court deposition, she would later confess: “I’ve always told O.J. what

he wants to hear.”

Now, the man who so shaped the life of Nicole Brown Simpson has come

to dominate the story of her death as well. Charged with murdering her

and her friend Ronald Lyle Goldman, it is O.J. Simpson who has

captivated the nation’s attention.

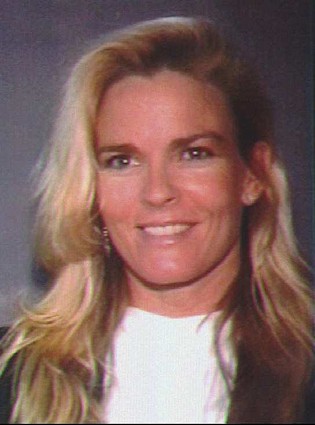

Nicole Simpson, meanwhile, has been reduced to the size of a poster

child, her friends and relatives say bitterly: Murder victim; battered

wife. Nothing like the strong, fun-loving woman they knew.

“It’s all O.J., O.J. right now,” said Rolf Baur, 46, a first cousin

who was raised by Nicole Simpson’s parents and whom she and her sisters

considered a brother.

Cynthia (Cici) Shahian, 39, a Beverly Hills friend, said: “I feel that Nicole has gotten lost in all this.”

Their Nicole, they say, was a 35-year-old wife and mother who had

never felt free to be just herself. Half her life had been consumed in

the tempestuous tit-for-tat that had been her celebrity marriage. In

what would be her final days, she had resolved to finally find her

identity.

But it was a wrenching endeavor. The relationship was a monstrous

edifice, friends and relatives say, a dark house of passion,

manipulation, money, love and violence.

Her quest, they believe, cost her her marriage.

Prosecutors say it cost her her life.

*

Nicole Brown Simpson was born May 19, 1959, near Frankfurt, Germany,

her mother’s homeland. Lou Brown, a native of Kansas, had met and

married Juditha Baur of the small town of Rollwald, where he was

serving with the Air Force.

Their first two daughters, Denise and Nicole, were born in Germany,

while Lou Brown worked at Stars and Stripes, the American military

newspaper; later, he started an insurance company for members of the

military.

Returning to the United States when the girls were toddlers, the

Browns lived first in Long Beach, then bought a large home with a

tennis court, a 16-foot-deep pool and a three-acre back yard in the

Royal Palm Estates section of Garden Grove. Two more daughters,

Dominique and Tanya, were born. Nicole and Denise started high school

there, at Rancho Alamitos High School, before the family moved to the

gated Orange County beach community of Monarch Bay in the mid-1970s.

At Dana Hills High School, what people remembered first about the

Brown girls was how good-looking they were. Nicole–they called her

“Nick”–was named homecoming princess by the football team in 1976; the

year before, Denise had been homecoming queen.

“Nicole was bubbly, always happy and smiling,” said Bill Prestridge, one of her teachers.

At the same time, however, she was “more mature than other

students,” he said. “You almost got the idea that she was ready to get

out of high school and go on to bigger and better things.”

Interested in modeling and photography, Nicole enrolled briefly at

Saddleback College in Mission Viejo, where high school friend Chris

Valdivia occasionally saw her around campus. By that time, he said,

everyone knew she was dating Simpson but her romance with the football

superstar didn’t seem to have changed her.

“She was just always really down-to-earth, really friendly,” Valdivia said.

‘Volatile . . . Relationship’

Nicole was barely 18 and just out of high school when she met

Simpson. After a two-week stint as a salesclerk in a boutique–during

which she made not a single sale, according to her divorce papers–she

started work as a waitress at the Daisy, a trendy Beverly Hills club

where Simpson was a regular.

The football legend, then 30, whose first marriage to high school

classmate Marguerite Whitley was faltering, began courting Nicole

almost immediately, Baur said.

Jo Hanson, a Dana Hills High School home economics teacher,

remembers Nicole coming back to proudly usher Simpson around to meet

her and sign autographs for those in the class one day. “You know

teen-agers,” she said. “They like someone older and more sophisticated

and she certainly did. He was everybody’s idol, of course, then.”

Within months, she had moved in with him, dropping out of community

college because Simpson “required that she be with him,” according to

the brief her divorce lawyer filed in 1992.

“It was a very passionate, a very volatile, a very obsessive

relationship. On both sides,” said actress Cathy Lee Crosby, a friend

of the couple who has known O.J. Simpson for 15 years.

One source close to the family said that even before they were

married, they had fights. During one, Nicole holed up in the bathroom

and telephoned her mother, the source said.

There were times, the source said, when she would move out and other

times when he would throw her out, tossing her clothes after her. Then

she would go home to her parents in Monarch Bay, but within days a

contrite Simpson would call and apologize, she would return and for a

time they would be loving again.

“They had many, many happy days together,” the source said. “It just seemed like something snapped sometimes.”

Although he was physically powerful, “she fought him back with words. She’s a strong person,” the source said.

She did not feel strong, though.

“I only attended junior college for a very short time, because

(Simpson) wanted me to be available to travel with him whenever his

career required him to go to a new location, even if it was for a short

period of time,” she said in an affidavit filed during her divorce. “I

have no other college education, and I hold no degrees.”

But with Simpson’s money and growing fame, who needed a career? And

her emotional contributions did not go unrecognized. Six months after

their wedding in 1985, when he was inducted into the Pro Football Hall

of Fame, Simpson thanked his new–and pregnant–wife for helping ease

his departure from sports.

Gazing down at his wife from the podium, he said she “came into my

life at what is probably the most difficult time for an athlete, at the

end of my career . . . (and) turned those years into some of the best I

have had in my life, babes.”

Two months after that, their first child was born, a baby daughter.

By that time, Simpson had become a national spokesman for Hertz and

several other companies, earning an estimated $1 million a year. They

moved to a $5-million Brentwood mansion on Rockingham Avenue. They had

his-and-hers Ferraris. A $1.9-million Laguna Beach house. A New York

pied-a-terre. Her pocket money allowance was $5,000 a month or more.

At the time, divorce records show, Simpson was supporting his mother

and two grown children from his first marriage; he was equally generous

with his in-laws. He hired Baur, first as the gardener at their estate,

then as the manager of his two Pioneer Chicken restaurants in Los

Angeles. At the same time, Baur’s wife, Maria, worked as the Simpsons’

housekeeper three days a week.

Simpson’s father-in-law Lou worked for him as well, running his

Hertz car rental franchise at the Ritz-Carlton Laguna Niguel. “O.J.

practically gave it to him,” Baur said.

He added that Simpson also paid for Nicole’s sister Dominique to attend USC.

It was an old-fashioned marriage in which she minded the baby and he

paid the bills. Every Easter, they gave an elaborate shindig at the

Rockingham mansion for all the relatives. The couple were a magnetic

presence at all the family gatherings. Baur has videotape, shot and

narrated by Simpson, of the day Baur brought his newborn son home from

the hospital. (As the family parades into Baur’s small Long Beach

apartment, Simpson can be heard teasing his brother-in-law about

whether he has “cleaned up for the boss.”)

In 1988, the Simpsons had a second child, a son. By all appearances, friends said, they seemed to have a perfect life.

“When they had parties at Rockingham, we had the best times. We

would play games–scavenger hunt, truth or consequences,” said Cora

Fischman, who lived down the street from the Simpson home.

Fischman was a doctor’s wife with three children, and through the

youngsters, she and Nicole Simpson became close friends and

confidantes. Her daughter attended private school with the Simpsons’

little girl and her youngest child went to the same preschool as their

son.

But if Nicole Simpson was a talented hostess and a conscientious

mother, she was also notable among her contemporaries for her

guardedness.

That caution extended even to Baur’s wife, who worked in the Simpson

house three days a week for almost three years. “She was the type of

person who would not say to me what her problems were,” said Maria

Baur, who said she often heard the couple exchange screaming, angry

words behind the closed door of the home’s office. “She wouldn’t talk.”

“The truth is, no one really knew her during her marriage,” said one

woman who had been friends with her since both were in their early 20s.

“She was never free to be herself or have friends. She wasn’t available

for that kind of intimacy.”

It was only much later, the friend added, that she began to suspect

there was more to Nicole Simpson’s guardedness than met the eye, that

there was something very wrong about her tendency toward sudden

cancellations and no-shows.

“She would have these horrible cramps. That’s what O.J. would tell

us. ‘Nicole has horrible menstrual cramps.’ Supposedly they kept her in

bed for days,” the friend said.

Eventually, however, the violent and jealous facets of the Simpson

marriage became common–if closely held–knowledge in their small

circle of friends.

Jennifer Young, daughter of Gig and Elaine Young, the late actor and

the Beverly Hills real estate agent, recalls bumping into Simpson one

day at La Scala in Beverly Hills while waiting to be seated for lunch.

Graciously, she said, he asked her and her girlfriend to join him, and

they did.

But when they left the restaurant, she said, Nicole Simpson roared

up in a black Mercedes, her blond hair in a bun, her face contorted

with rage.

“She was screaming at the top of her lungs in the middle of Rodeo

Drive,” Young said. “She was, like, ‘If you’re f—— going to cheat

on me, why don’t you pick somebody f—— pretty?’ ”

It was that sort of conflict, her friends said, that touched off their most serious fights.

“He’d cheat. She’d find out. She’d get angry. She’d confront him.

She’s a strong girl and she’d confront him. And they would fight,” said

one longtime friend.

New Year’s Day Assault

This, friends say, was the backdrop on New Year’s Day, 1989, when

the now-infamous beating occurred. According to police reports, as

officers arrived at the Simpson estate at 3:30 a.m., Nicole Simpson

burst from the hedges, rushed across the lawn in her sweat pants and

bra and collapsed against the gate-release button.

“He’s going to kill me, he’s going to kill me,” she cried, according

to the report. “You never do anything about him. You talk to him and

then leave.” Her eye was black. Her lip was split. His handprint was

still on her neck.

“I don’t want that woman sleeping in my bed anymore!” Simpson

shouted, according to the report. “I got two women, and I don’t want

that woman in my bed anymore.”

Simpson–who later pleaded no contest to spousal battery–has since

said the incident was an isolated one, and that he took the blame to

head off bad publicity for him and his wife.

Later, outsiders would wonder why Nicole Simpson did not end the

marriage then. But to their friends and relatives, it seemed that by

that time their entanglement was so powerful it could never be sundered.

Baur said she stayed “because she loved him. And he loved her so

much.” And there were her hopes, friends said, that her children would

have a stable home.

“She said all she wanted was to be a good mom like her mom,” Fischman said. “All she wanted was a simple life.”

But “she was afraid that if she left, a lot of people would be left

out in the cold,” one intimate said, referring to her relatives’

financial connections to Simpson.

Finally, however, in early 1992, Nicole Simpson filed for divorce.

By that time, her father was no longer working for Simpson. The car

franchise, Baur said, had never been profitable, and Simpson had

finally sold it. Lou Brown, whose other business ventures had included

commercial real estate investing and carwash ownership, went into

semi-retirement.

Baur, too, found himself out of a job, although according to court

documents his loss was a function of local events. In divorce records,

Simpson reported that the Los Angeles riots destroyed his one

profitable Pioneer Chicken franchise, forcing the shutdown of the other

as well.

Baur, while confirming the financial connections between his

relatives and Simpson, said he does not believe that Nicole Simpson

felt compelled to prolong her troubled marriage because of any family

dependence on her husband.

“I don’t think that’s fair,” Baur said, “because not everybody was

on his payroll and we all worked hard for our money. He had jobs to do

and we did them.” Other family members declined comment.

The divorce left Nicole Simpson single again for the first time

since her teens. She was awarded $433,750 and $10,000 a month child

support. She moved into a rented house five minutes from the mansion,

then bought a nearby condominium. Friends said she was as dutiful a

mother as ever, handling the car-pool, showing up at all the school

functions, shuttling her little son to karate lessons and her daughter

to dance class.

But suddenly, they said, a freer, lighter Nicole Simpson also began

to emerge. The transformation in her, friends said, was palpable.

“She became Nicole Brown , her own person,” Fischman said. “She started all over again.”

She got friendlier with old acquaintances, developing a cadre of

perhaps half a dozen women friends–Fischman, Shahian, Westside

socialite Faye Resnick, actress Robin Greer, and Chris Jenner (wife of

athlete Bruce Jenner), among others. They were a stunning crew (“We’re

all pretty cute,” laughed one Westside divorcee who developed a close

bond with her on a trip to Cabo San Lucas. “When we went out to dance,

we had to dance with each other to keep the wolves away.”)

She threw potluck dinners by candlelight. She would drop the

children at school and go jogging–six, nine, 10 miles at a clip–in

skintight workout clothes. She would tuck the children into bed at

night, recite the Lord’s Prayer with them in German, and then leave

them with a sitter while she went out dancing till last call.

Bartenders would watch, mesmerized, as she hit the dance floor,

dripping sweat, in her tank top and strategically ripped jeans,

slapping down her platinum American Express for another round of Patron

tequila.

Other nights, she would don a black mini-dress and meet her new

girlfriends for dinner at Brentwood’s Toscana restaurant, splurging on

$150 bottles of Cristal champagne. Even so, what people remembered was

her down-to-earth disposition.

“She was totally a real person,” said an acting teacher who ran into

her intermittently over the years. “She had nice things, but she

treated her Ferrari the way other people treat their Volkswagen. She

was such a no-attitude person.”

Her friend Shahian added: “She was just so generous–with her money, herself. She’d have six, seven kids over there at a time.”

Still, the legacy of the marriage cast its shadow. She couldn’t help

it. It was the standard against which she defined herself. Simpson

detested smoking; she would sneak cigarettes. He was fastidious; she

boasted about what a mess her new home was. During their marriage, he

encouraged her to wear only the finest of clothes, deluging her with

French Fogal stockings at $60 a pair. On her own, friends said, she had

to be prodded to go shopping and showed up at black-tie dinners

barelegged.

And Simpson, friends said, was ubiquitous. Affluence

notwithstanding, Brentwood is a small town. Gossip echoes from every

iron gate and grocery aisle. A five-minute drive could tell him if a

stranger was parked in his ex-wife’s drive. She could flip on the TV

and see who was sitting next to him in the stands at a football game.

She dated, friends said, although the dates were few and far

between. There was Keith Zlomsowitch, a restaurateur she had met in

Aspen and later at Mezzaluna, a trattoria-style Brentwood watering

hole. Friends said he doted on her, but she was not ready for a serious

relationship. One night, they said, Simpson drove past her house and

through the front window saw Zlomsowitch on the couch with her; she

stopped dating him very soon thereafter.

(Zlomsowitch could not be reached for comment. His parents confirmed

that he had once been briefly involved with Nicole Simpson and had been

a pallbearer at her funeral.)

There were two other men as well, the friends said–an aspiring

actor with whom she had a brief fling, and later, a tentative,

six-month romance with a 24-year-old law clerk she had met in her

divorce lawyer’s office.

But about 18 months after leaving Simpson, she began seeing a

counselor, one friend said, a man they had all heard about in Aspen who

specialized in group therapy.

“We all went for a couple of months,” the friend said, “and then

Nicole went for the intensive, which was about $4,000, where she would

go every day for, like, a month.”

When she emerged, the friend said, she announced that she had made a

decision: “She called me up and said, ‘I want my husband back.’ ”

“She called O.J. up,” the friend said. He refused to take the call,

“so she drove over there in just her zoris and a little summer shift.”

He told her he was doing fine without her, but when she got home, he

called to say he had changed his mind and wanted to reconcile.

Before long, their relationship was tempestuous again. “He broke the

back door down to get in,” she pleads on a widely aired 911 tape from

Oct. 25, 1993. “He’s f—— going nuts. . . . He’s going to beat the

s— out of me.”

On the tape, she tells the operator that Simpson had been leafing

through her photo albums and had come across a picture of an

ex-boyfriend (friends said it was Zlomsowitch).

On and Off Reconciliation

Still, the reconciliation continued, on again, off again, friends

said. Now they were living at Rockingham; now she had bought a condo of

her own. Now the relationship was doomed; now they were together for

Christmas. Now she had had enough; now it was her birthday, and he had

given her a platinum bracelet studded with sapphires and rubies and

diamonds.

But a week after her birthday, Baur said, she gave back the bracelet

and told Simpson that there would be no reconciliation and no hope of

one.

“Nicole wanted to be free of him, she wanted to live her life with

the children and raise them away from all this fiasco of the marriage,”

he said. “She wanted to have a happier, more peaceful life. . . . This

time it was different. She really meant it and he knew it.”

Afterward, he said, she seemed relieved. In a matter of days,

Simpson was being seen with model Paula Barbieri, whom he had dated

right after the divorce. Donna Estes, a writer and film producer who

has known the Simpsons for the last six years, said she saw him with

Barbieri at a Memorial Day golf outing, but that before dinner,

Barbieri suddenly left.

Later, Estes said, Simpson confided that they had gotten into an argument when he confessed that he still loved Nicole.

But on the night before Nicole died, Simpson showed up at a

black-tie event with Barbieri on his arm. Friends said Nicole was

relieved when she found out: “She was happier than hell about it,” said

a woman who spoke to her on the night she died.

Still, the next day, at their daughter’s dance recital, her friends

said, Simpson and Nicole scarcely looked at each other. A friend who

was there said she made it clear he would not be invited to the family

dinner afterward.

As always, their friends said, they made a stunning pair, she in her

backless black dress, he in silk shirt and jeans. Three folding chairs,

wide as a demilitarized zone, marked the chasm between them as their

little girl danced. In less than six hours, Nicole Brown Simpson was

dead. |

Los Angeles Times file photo

Los Angeles Times file photo