Harry Houdini in “The Grim Game.”

Long considered mostly lost, Harry Houdini’s second film, “The Grim Game,” re-premieres in its entirety Sunday, March 29, 2015, at the TCM Classic Film Festival, 96 years after it was released. A suspense thriller packed chock-a-block with hair-raising stunts, “The Grim Game” smartly capitalized on an accident during filming to pack in audiences, obscuring some facts along the way.

Self-liberator and escapologist Harry Houdini ranked as the world’s top illusionist in the 1910s. Hungarian-born Houdini “magically” escaped from handcuffs, chains, strait jackets, and locked cases in performances around the world, thanks to careful planning and special keys. He masterfully employed newsreels, magazine, and newspaper coverage to exploit his fame and derring-do.

Mary Mallory’s “Hollywood land: Tales Lost and Found” is available for the Kindle.

“The Grim Game,” Great Falls Daily Tribune, Oct. 31, 1919.

The master magician recognized the importance of film for promoting his appearances as well as documenting his career for posterity. By the mid-1900s, Houdini included footage of his public escapes as part of his act. In 1909, he shot a documentary for the French company Cinema Lux entitled, “The Marvelous Exploits of the Famous Houdini in Paris.” Producer B. A. Rolfe produced the 15-part serial, “The Master Mystery,” starring Houdini in 1918 to release in conjunction with a novel. It featured strong man Houdini performing strenuous stunts as well as capturing many of his elaborate escape tricks for the camera.

“The Master Mystery’s success led Famous Players-Lasky in early 1919 to sign the illusionist to a two-picture deal to star in action-packed thrill pictures. The company hired magazine and scenario writers Arthur B. Reeve and John W. Grey to craft a creditable story around which to center Houdini’s amazing stunts. The company began filming in May under the direction of young director Irvin Willat. The story concerned reporter Harry Hanford (Houdini) looking for a big scoop for his newspaper and to pay off a debt, plotting with some gentlemen to kidnap a millionaire uncle and take him to the mountains, where he would be supposedly murdered, before Hanford revealed all in the paper. Instead, the old man is murdered, forcing the reporter to solve the mystery and save his life.

All the Lasky stars were supposedly eager to meet the illustrious illusionist, with some thinking up elaborate traps from which he easily escaped. The company doled out fictional press releases promoting his great escape skills, such as the one printed in the October 12, 1919 Washington Times. This story claimed that Houdini had accepted a challenge from four naval officers while making the picture. He lashed himself to the muzzle of a cannon located in the middle of Pershing Square, the weapon was loaded, a fuse attached, but the police prevented men from pulling the trigger. Houdini went ahead and extricated himself in two and half minutes from ropes tying him to the cannon, which took the challengers six minutes to tie.

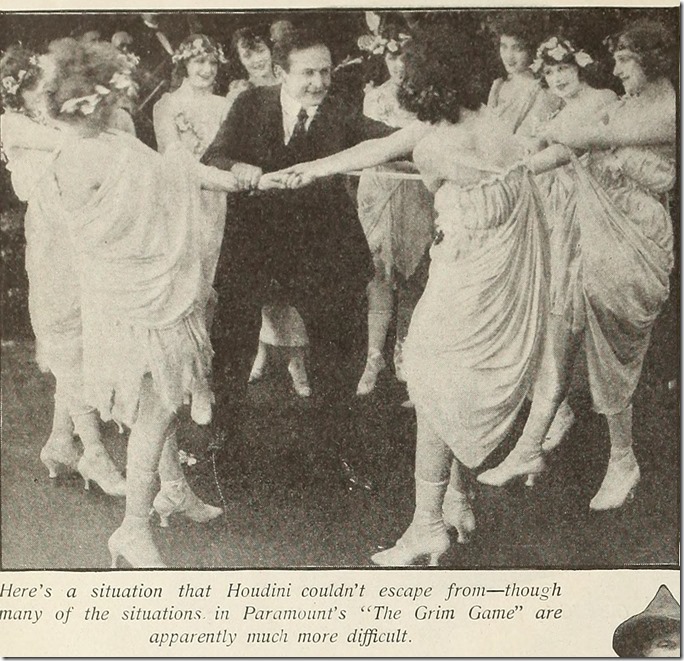

Harry Houdini in “The Grim Game,” Picture Play Magazine.

At the end of May, a planned stunt went awry, leading to the biggest publicity break for the film. While Houdini and publicity materials would claim that the studly magician performed the stunt, actual newspaper accounts reveal the actual story. The June 1, 1919 Los Angeles Times states that three aircraft leased from Mercury Aviation of DeMille Field to the Santa Monica area on the afternoon of May 31 to shoot a sequence in which a stuntman would climb out of a moving airplane, dangle over a plane below, jump into it, take the wheel and successfully land the plane, standing in for Houdini’s character. Director Willat followed the two chasing aircraft in another biplane to film the exciting sequence.

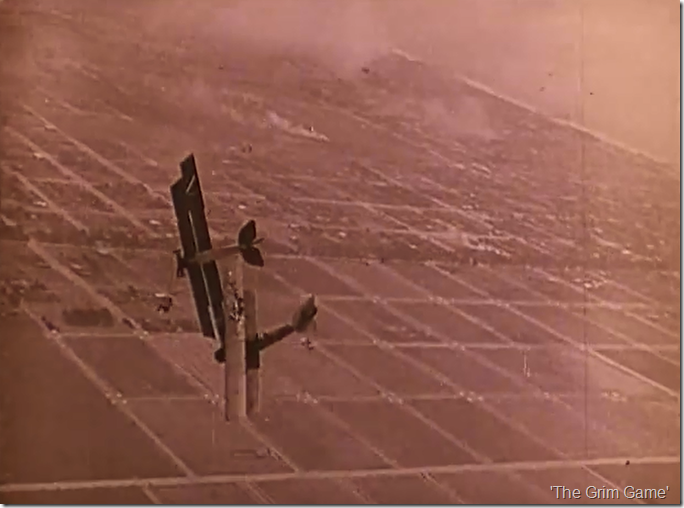

Former airman Robert E. Kennedy climbed out of his speeding craft onto a dangling rope above the Lewis Ranch near San Vicente Boulevard and 26th Street in Santa Monica, from which he intended to jump into the moving plane below. Instead, an updraft of air caused the two planes to collide, leaving Kennedy hanging for dear life to the flimsy rope ladder almost 3000 feet in the air as the flying machines hurtled towards the ground. Kennedy miraculously survived being crushed between the two planes as the pilots expertly righted the two planes, with one landing safely and the other upside down a short distance away. The paper notes that pilot Lt. D. E. Thompson managed to keep his damaged plane from throttling into a nose dive, though he couldn’t control the plane’s movements, his propeller was smashed, and most of the upper wing had been ripped away. He successfully landed the plane, though upside down. The lower aircraft piloted by Lt. C. V. Pickup gently glided to a stop on a freshly plowed bean field. Director Willat, called Irwin Willett in the story, continued shooting, capturing the sequence on film.

The Associated Press wired the story across the country, and it appeared weeks later in several other newspapers and trade magazines. The New York Tribune published frame enlargements from the actual footage along with a story on July 6, 1919, claiming it the first ever actual airplane collision captured on film. They noted the planes were performing a stunt involving “former army pilot Robert Kennedy” for “The Grim Game,” stating, “The three extraordinary photographs above are part of a motion picture film which was recording the flight from another ‘plane at the time of the accident. This collision was unpremeditated and miraculously resulted in the injury of but one pilot.” Wid’s Daily reported the accident July 7, 1919, saying it occurred during the filming for “The Grim Game,” with an airman dangling from a rope.

In July, Houdini broke a bone in his left wrist while fighting four burly extras in the film, snapping his wrist, per both Wid’s Daily and Motion Picture News, with Motion Picture News calling the production a serial. Variety claimed he recuperating after breaking his arm while risking his life in the plane jump. Though he finished the scene, shooting was delayed two weeks while the strong man healed. During this time, Famous Players-Lasky negotiated a deal with the Society of American Magicians, founded by Houdini, in which the organization agreed to promote the picture, a fact the Lasky Company would employ in selling the picture to exhibitors.

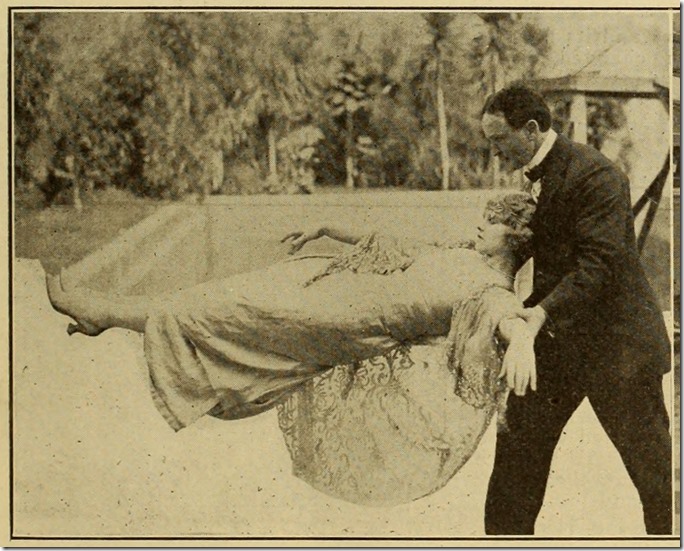

Harry Houdini with Wanda Hawley, Moving Picture World.

‘The Grim Game” quickly opened in New York’s Broadway Theatre in late August, with Houdini himself appearing at every performance. It was here that the myth of Houdini surviving the botched accident took root. Like a current political party, Houdini and Famous Players-Lasky began repeating a false story so many times that the public began to believe it.

Houdini offered $1,000 to anyone who could prove the collision wasn’t authentic, but there was no mention in his bet that he performed the stunt. He would claim the next year to his biographer that he had been performing the stunt at the time of the crash, which made it into print.

The Lasky Corporation, however, falsely played up the idea of Houdini almost losing his life in publicity, realizing the actual footage of the collision was the ultimate selling card. They created a large ad noting that the Broadway Theatre was forced to turn away crowds who found the film the great suspense thriller ever. “The spectators are held spell-bound from the opening. They gasp! They grip their seats! And when the big climax – the aeroplane collision – comes, they break loose in a wild roar of applause!” A drawing of Houdini hanging on a rope from the biplane dominated the ad.

They included press releases in their press kit claiming that Houdini almost lost his life performing the stunt, which many theaters employed word for word in their local newspapers. One such ad appeared in the Cedar Rapid Evening Gazette January 15, 1920, stating, “SEE him above everything else, in the most astounding feat ever caught by a motion picture camera…An accident absolutely authentic and reported by the Associated Press.” They even reported he performed every one of his stunts. The Palatka Daily News quoted from a canned release in 1920 explaining Houdini’s heroics in surviving, and giving his reason for performing in the film, “The present generation can see me in person, but I want my most thrilling feats perpetuated on the screen, so that people in later years can assure themselves that I actually did them.”

The airplane collision in “The Grim Game.”

Early reviews found the film packed with “fast and furious action,” but filled with stilted acting by Houdini. The New York Tribune in its August 27, 1919 review felt the film took too long to get started, but found the last three reels crammed with action. Variety’s August 29, 1919 review believed the film didn’t live up to its reputation, finding the stunts not any more elaborate than regular serial stunts. They thought the unplanned airplane accident gave it the best hook. While they noted Houdini crawls out of chains, throws himself over a building wearing a strait jacket, frees himself from a strait jacket while hanging upside down on top of a six story building, frees himself from a bear trap, and the like, they felt the stunts weren’t effective because no one was certain Houdini was actually performing them.

Other reviewers mostly praised the film’s thrilling action sequences. Photoplay’s November review called it a “trick melodrama” featuring Houdini’s best stunts – escaping strait jackets, slipping off handcuffs, and featuring other amazing escapes. Paramount ran ads claiming critics described Houdini’s exploits more thrilling on the screen than in real life. “The Grim Game” will thrill America as it has never been thrilled before.”

Houdini to the rescue after surviving a plane crash in “The Grim Game.”

The film performed fairly well across the country. Exhibitor’s Herald printed comments from local exhibitors about how films performed in their community, and some described the film doing okay for them. Bert Golman of St Paul’s New Princess Theatre stated the film did well with men, but only so-so with women. W. G. Mitchell of the Majestic Gardens Theatre in Kalamazoo, Michigan thought the advertising was much too strong, leading them to expect more than they received. A. N. Miles of Eminence, Kentucky’s Eminence Theatre thought it was such a relief from all the love stories. “There isn’t a kiss in the whole picture and the only person who objected was an old maid.” One exhibitor thought it possessed as much action as a 15-part serial.

Decades later, Mrs. Houdini donated her husband’s print of the film to the Houdini Museum, who eventually gave it to a magician. After recent negotiations, he handed over the only known complete print, which has been restored and will premiere at the TCM Festival, before eventually appearing on the channel itself. The TCM Festival often premieres films long considered lost or kept from distribution due to rights issues. The 2015 Festival is entitled, “History According to Hollywood,” featuring screenings of such films as “The Sound of Music,” “Lawrence of Arabia,” “Inherit the Wind,” “Young Mr. Lincoln,” “Rififi,” “Too Late For Tears,” “Malcolm X,” “The Picture Show Man,” and “Gunga Din,” interviews with Norman Lloyd, Sophia Loren, Shirley MacLaine, and Peter Fonda, with special programs like “Hollywood Home Movies,” “The Dawn of Technicolor,” and “Return of the Dream Machine.” Hope to see you at the movies!

Yes, they walk among us. God help us.

LikeLike

Great to see the aerial scene of Houdini’s film “The Grim Game”

LikeLike

Pingback: LINK: L.A. Daily Mirror pinpoints Houdini’s plane crash | harryhoudinicircumstantialevidence.com

Pingback: 10 Fantastic Firsts In Film | AbcNewsInsider #1 sources for news

Pingback: Houdini – Keaton – The Grim Game – Cops | Chaplin-Keaton-Lloyd film locations (and more)

Pingback: Houdini – The Grim Game’s historic LA landmarks | Chaplin-Keaton-Lloyd film locations (and more)