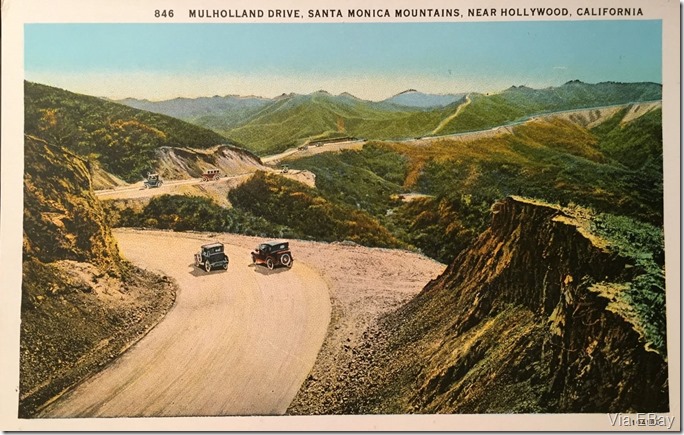

A postcard showing Mulholland Drive is listed on EBay with bids starting at 99 cents.

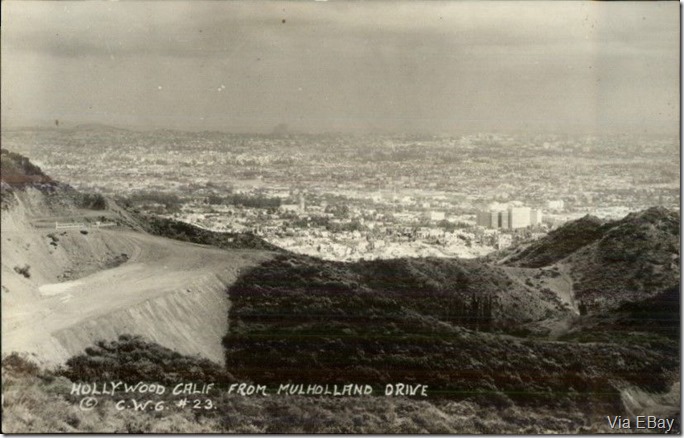

Spanning 21 miles from Hollywood to Calabasas, Mulholland Drive provides a dramatic dividing line between Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley, providing both residents and tourists with gorgeous panoramic views of the metropolitan area. While providing a great scenic outpost to the city, its construction aided development of its surrounding foothills as well as provided a route to lay water trunk lines to the area.

Water guru William Mulholland himself first conceived the construction of such a highway in 1914 as both a way to celebrate the glories of the Los Angeles areas as well as to provide a more accessible route for conveying water to residents of the foothills and surrounding areas.

“Hollywood Celebrates the Holidays” by Karie Bible and Mary Mallory is now available at Amazon and at local bookstores.

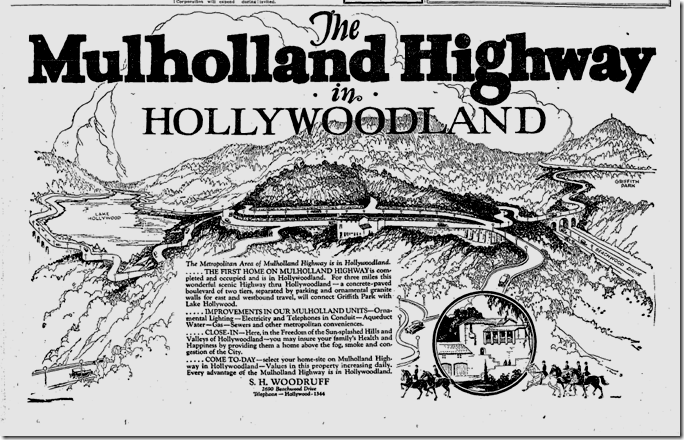

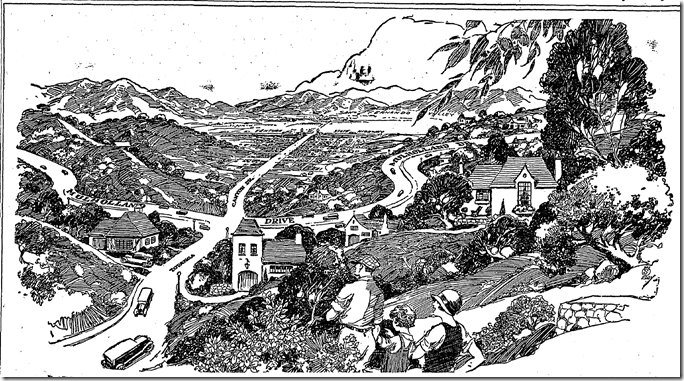

Mulholland Highway in the Dec. 18, 1924, Los Angeles Times.

As the metropolitan area had exploded in population during the first two decades of the twentieth century, so did the Santa Monica Mountains. Angelenos were building homes in the rustic hillsides, requiring water and other city services. Developers and large landowners such as Edwin Doheny, Myra Hershey, Harry Chandler, and Harry Merrick looked to capitalize on their real estate investments.

On December 14, 1922, prominent property owners met at the Hollywood Country Club in Studio City to organize the Hollywood Hills Improvement Association to better the roads leading to their property, thereby making it more valuable. They resolved to advocate for the construction of Mulholland Skyline Drive or Mulholland Boulevard that would “provide a pleasure drive 30 miles in length, uncontested flowing one-way traffic on each of two parallel highways…thus creating the world’s most wonderful highway,” as reported in the October 6, 1923 Los Angeles Times.

They incorporated December 31, 1922, setting up a preliminary $5,000 fund through member donations to conduct engineering studies and construction possibilities. City Engineer Dewitt Reaburn had begun surveying the proposed route the day before for the organization after the association retained his services. The December 31 edition of the Times stated that the group wanted to turn the Hollywood foothills in to the greatest permanent home, country estate, and weekend lodge district in the United States. As Harry Merrick, president of the Hollywood Country Club development stated, “Los Angeles has an asset that it only dimly realizes.”

The proposed road would race along the peaks of the Santa Monica Mountains from the Cahuenga Pass to Topanga, helping alleviate traffic on lower parallel roads. Discussion amongst the parties led to expansion of the proposed highway all the way to the Vermont Avenue entrance to Griffith Park, per the December 24, 1922 Los Angeles Times.

Development of such a road would open automobile traffic to land along the San Fernando Valley, Hollywood, and Beverly Hills slopes of the Mountain available for sale, create new roads connecting the Valley with Los Angeles, as well as easing the laying of pipes providing water to hillside residents. Most of all, it would display the beauty of the wide open San Fernando Valley and growing metropolis of Los Angeles, a potent draw for tourists.

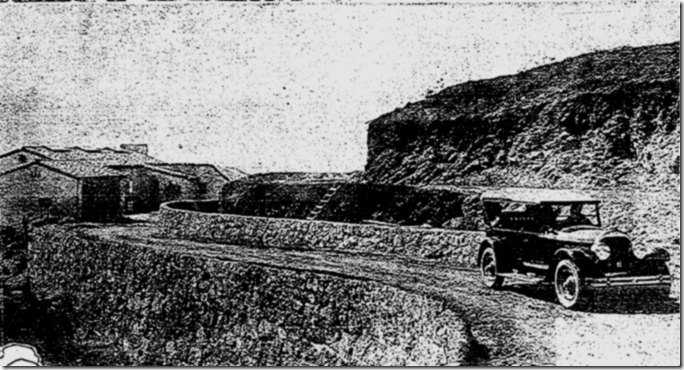

Separated lanes, shown in the Oct. 19, 1924, Los Angeles Times.

Hollywood Hills Improvement Association supporters of the project included Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce Secretary Frank Wiggins, City Councilmen Cornelius, City Planning Commission President A. G. Bartlett, Dr. Edwin O. Palmer of Hollywood, author Edgar Rice Burroughs, Bel Air developer Alphonso Bell, M. H. Sherman, Los Angeles Times publisher Harry Chandler, operator of the Beverly Hills Hotel Myra Hershey, Harry Merrick, President of Hollywood Country Club William F. Holt, city and county engineers and commissioners, the Hollywood and Los Angeles Chambers of Commerce, and the Los Angeles Realty Board.

Members proposed a thirty foot wide road, with a combined twenty four wide right of way lined with walks and bridle paths making nature more accessible to residents. The group would advocate that the city raise bonds to construct the road, organizing petitions to the city, county, and State as well as hosting talks by experts to talk up benefits to landowners and residents. To aid in fundraising efforts, the group also formed Municipal Improvement District Number 22 as the legal entity for the payment of property taxes financing construction.

Creating such a road would allow construction of lateral canyon roads to alleviate congestion and provide extra traffic routes in Coldwater, Benedict, and Sepulveda Canyons, in addition to the already in use Laurel and Topanga Canyon Roads. The Improvement Association proposed building a San Fernando Valley road in the flats that would parallel Ventura Boulevard as well. Better transportation through the area would allow easier construction for residential, commercial, and industrial property all throughout the foothills.

City and County officials quickly praised the proposal and joined in support of a bond measure to add these capital improvements. The Hollywood Hills Improvement Association worked with City Planning Commission Engineer John R. Prince and City Engineer Griffin in removing brush throughout the canyon in order to create bridle paths every half to three quarters of a mile. The group also suggested the possibility of building a stables on the San Fernando Valley side from which horses could be rented for riding. Some developers employed the slogan, “Greater Than the Riviera of France” in advocating for construction, with thirty applying for proposed subdivisions in the area by October 6.

City support helped speed the referendum through the ballot process per “Metropolis in the Making: Los Angeles in the 1920s.” When Reaburn certified the road’s proposed boundary, the city clerk took only a week, an astonishingly short time in civic matters, to check signatures against voter rolls. The City Council scheduled the bare minimum public notice period before setting the referendum for October 9, 1923.

A postcard showing Hollywood as seen from Mulholland, listed on EBay as Buy It Now for $6.89.

While lobbying city, county, and state officials, the group put together their proposal for the fall 1923 city ballot and spent eight months soliciting signatures to gain its placement on said ballot. Along with city officials, they organized meetings during the summer and fall of 1923 describing the benefits of such a proposal, from increasing property values to facilitating the accessibility of water on both sides of the foothills. They also tried to alleviate foothill residents’ concerns regarding possible fire dangers, and told Laurel Canyon District residents on October 6 that without the road, they could not bring water easily into the area, with water issues already serious.

The ballot measure passed by a two to one margin on October 9, and the city raced ahead in finding a source to pay for the $1 million construction costs. The City Council accepted the one bid by a syndicate composed of local investment houses led by the California Company for bonds constructing the Highway November 16, 1923. These bonds, which went on sale in January 1924, would be paid over the next forty years through a special increment in property taxes by those in the improvement district.

William Mulholland symbolically dug the first shovelful of dirt December 10, 1923 in a ceremony attended by Hollywood Hills Improvement Association and Hollywood Foothill Association members, city, county, and state officials, and celebrities, after a luncheon hosted by the Woodin Hunt Club and Hollywood Country Club. Mayor Cryer also took part in shoveling dirt for the grand project, with the December 16 Times stating, “Mulholland Skyline Drive will stand not only as a monument to the work of a man who has had an important part in the upbuilding of Los Angeles but it will exist also as striking evidence of what can be accomplished through energetic and unflagging effort.” Former Secretary William McAdoo stated that construction of Mulholland Skyline Drive would provide great material value and add to the attractiveness of the city.

On December 14, Taft Realty Company, owners of the Hollywood Knolls area and Hollywoodland developers announced they would pay for construction costs of the Highway from the Cahuenga Pass to Griffith Park. Holly Leaves reported that same day that the Drive would pass under Hollywoodland’s electric sign and across the dam under construction in Weid Canyon. Unfortunately the route through Hollywoodland and into and out of Griffith Park would never be completed.

Thanks to the work in promoting Mulholland Highway, the Council approved extending Wilshire Boulevard from Orange Drive through Westlake Park in late 1923 as well.

Mulholland Drive is featured in a display ad in the June 8, 1924, Los Angeles Times.

Five construction camps holding about sixty men each were established along the route to begin work in earnest in January. After the rains stopped, additional men and even women would be hired to facilitate completion as the city established the smoothest route possible. On February 23 the city announced they would ensure construction of the Highway remained far behind the Hollywood Bowl and were considering their options in constructing a bridge across the Cahuenga Pass. The City Council and Board of Public Works voted March 29, 1924 to prevent construction of small parks along the route, instead providing that small overviews be provided instead.

The Mulholland Highway Protective Association took out newspaper ads September 27, announcing a committee would oversee architectural restrictions on construction projects along the highway. Other restrictions prevented construction of studios, theatres, hotels, billboards, and electric signs along the road for the next fifty years, and allowed construction and ownership by white persons only.

In late spring 1924, the city threw a huge party announcing completion of the main Mulholland Highway, featuring a flyover of 80 airplanes, a parade with 2000 military personnel and bands, a wild west show organized by Tom Mix, a scattering of roses, and a ceremonial drive by a large automotive caravan along the scenic road, celebrating their accomplishment.

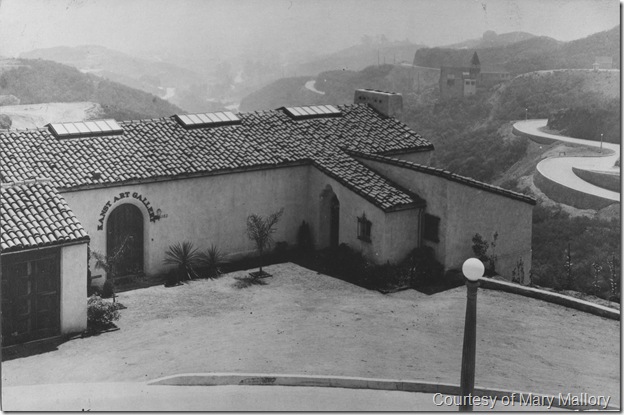

The Kanst Art Gallery, courtesy of Mary Mallory.

Hollywoodland announced construction of the J. F. Kanst house at 6182 Mulholland Highway, June 14, 1924, the first home to be built along the new scenic drive. Designed by John L. De Lario and Harbin Hunter, the residence also served as Kanst’s art gallery for several years.

On St. Patrick’s Day, March 17, 1925, the newly christened Mulholland Dam was dedicated, named for the man who designed and supervised its construction, the man most instrumental in providing the metropolis of Los Angeles with water. Mulholland Highway crossed the dam, linking two of the man’s most important projects. By April 12, the road extended from Cahuenga Pass through Lakewood, the area surrounding the dam. Though Hollywoodland announced the beginning of construction on the road towards and through Griffith Park on May 10, it never was completed.

While the grand Mulholland Highway was approved and constructed in record time, it did little to benefit the developers who pushed for its construction. Real estate began a slow descent in the late 1920s before the stock market crash in 1929, and the widening of Cahuenga Pass prevented much traffic from traveling its route.

Pingback: Link Chum Stew: What’s In The Pot This Week, Johnny? « Observations Along the Road

Are there any maps/plans showing how it was supposed to extend through Lakewood/Griffith Park?

LikeLike