“Weegee, Weegee, Tell Me Do,” courtesy of Mary Mallory.

What we know as the game of Ouija evolved out of spiritualism practices into a major fad of the early twentieth century. While some denounced it as a form of devil worship, others enjoyed its entertaining qualities or ties to their spiritualism practices. Its ability to answer questions or possibly foresee the future were employed as gimmicks to sell popular entertainment to audiences in a variety of fields.

Born out of a need to connect with the souls of departed loved ones and friends, spiritualism helped its practitioners feel at peace and ease in the world by asking questions of these spirits. It sprung out of potentially supernatural events at a Hydesville, New York farmhouse in 1848, when the Fox family experienced mysterious raps in the night. Youngest daughter Kate Fox challenged the ghostly spirit to repeat in raps the number of times she flipped her fingers; thus establishing a form of communication, these raps were employed as a way to answer questions.

“Hollywood Celebrates the Holidays” by Karie Bible and Mary Mallory is now available at Amazon and at local bookstores.

By the 1860s, the practice of speaking with spirits through sittings was popular, particularly in France and England, and eventually led to the formation of its own spiritual organization. Opposition from those who compared it to witchcraft or necromancy led to condemnations and even violence.

Elijah H. Bond developed a game based on the practice of mediums communicating with spirits in 1890 when he created the game of Ouija and its “Talking Board.” He assigned his creation to the Kennard Novelty Company, founded by Charles H. Kennard, Harry Welles Rusk, William H. A. Maupin, Col Washington Bowes, and John F. Green and incorporated October 20, 1890 with $30,000 at Kennard’s failing fertilizer factory at 220 S. Charles Street in Baltimore, Maryland. Ouija earned patent #446054 in 1891, later trademarked by the company on February 3, 1891. What started as a game eventually gave way to an obsession, and still exists 164 years later. Its popularity would influence the creation of songs, plays, and even movies featuring the little board and its communicating skills.

Ouija, pronounced and sometimes called Weegee by its practitioners, quickly attracted followers, both those interested in communicating with spirits and others just looking for fun. The game consisted of a “Talking Board” filled with letters and numbers and the words “yes” and “no.” A planchette on which two people would place their fingertips would select words based on vibrations. As with other incredibly popular toys, the fad would explode in popularity for a few years before dying away, only to be revived again later.

Advertisements appeared as early as January 1, 1892 promoting the talking board, which cost 98 cents. One 1892 ad explained how it talked of past and future, while an advertorial in the Rochester Weekly Republican on January 16, 1892 called it “the most wonderful invention of the 19th Century,” major hyperbole, claiming its results passed that of second sight, mind reading, or clairvoyance, and that it was “thoroughly tested” and “demonstrated” at the United States Patent Office before gaining its patent.

Some newspapers reported as early as July 1892 that it was created as a toy but exploded in popularity when discovered by spiritualists. They also denigrated it by claiming its followers were inclined to practice evil things or utter disreputable words after playing with it.

Those fearful of anything new condemned it and its followers, claiming it was irreligious and evil, leading its practitioners into paths of darkness. They described many of these people as gullible, excitable, or nervous, easily swayed by temptation or simplicity. Foes derided it, claiming it caused mental or emotional issues, particularly among women. They claimed it allowed those susceptible to scams or mental influence to become victims of its power.

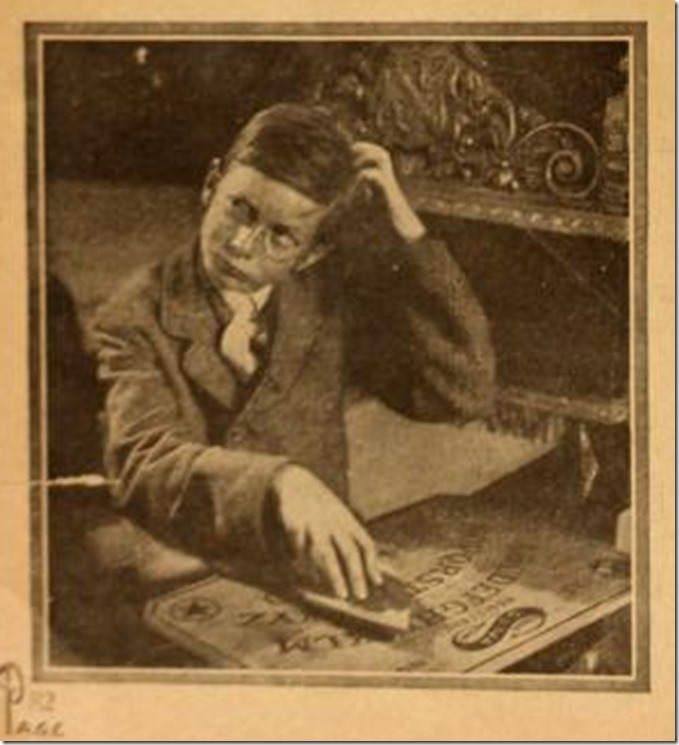

Wesley Barry and a Ouija board.

The November 13, 1917 Los Angeles Times derided people who played with Ouija as believing in superstition and the occult, stating, “It is deplorable that people who otherwise evince an unnatural amount of common sense should thus become the victims of inanimate objects which have neither intelligence nor power. Will superstition ever be eliminated from the mind of humanity?”

Many men upset with their wives or female relatives employed the practice or playing with a Ouija Board as a sign the women were insane, mentally defective, or the like, particularly when they were seeking divorce or a greater share of an inheritance in decisions that did not favor them. From evidence in newspapers, only men employed these strategies in court cases, with the courts overwhelmingly finding for them and sentencing women to insane asylums or overturning wills.

In 1903, Frederick Olcott and his brothers Hans and Frank worked to break their father Joseph’s will through claims of the influence of spiritualism and ouija. They claimed their father and sister, Mrs. Josephine Kroff, were avid practitioners of spiritualism, with Mrs. Kroff working as a medium employing a ouija board. They were incensed their father left his entire $80,000 estate to her.

Charles Delaney of Portland, Oregon filed for divorce from his wife Pauline in July 1910 when he claimed she became obsessed with the game, trying to decipher whether he was cheating on her. Mrs. Delaney was institutionalized for a short time while Mr. Delaney was granted his divorce.

The July 31, 1917 Los Angeles Times reported that Judge Crow committed Lucy E. Palmer of Oxnard to an asylum per her husband’s statement that she believed in Ouija. Any time a woman questioned authority, asked for greater freedom or power, or acted independently, the simple act of even playing the game could be employed as a defense to lock her away.

Businessman Gaylord Wilshire, the stepson of Mrs. Susan Wilshire, contested probate of a will leaving most of her $800,000 estate to the YMCA to help sailors and soldiers in training camps, claiming she was mentally incompetent from using a Ouija Board.

Dr. William J. Hickson, director of Chicago’s leading psychopathic laboratory thought people who played the game became obsessed with it to evade responsibility, rendering them insane or deluded, per the February 14, 1920 newspaper. At a July 1920 medical conference in Philadelphia, doctors discussed whether the Ouija fad produced an increase in nut cases, or whether nut cases led to the fad. Directors of state hospitals claimed it unbalanced minds, mostly played by people of “highly strung and neurotic natures.”

Seventh Day Adventists fought against seances and Ouija in March 1920, with ministers of various religions calling it a “Toy of the Devil” at the same time.Dr. Herbert Booth Smith of Immanuel Presbyterian claimed that Ouija could lead to devil worship as there were more of these games than Bibles in the homes of university students.

In 1919, Ouija exploded in popularity again across the United States, possibly due to the tragedy of World War I and the loss of so many people. The January 8, 1919 Los Angeles Times described an increase in the occult, seances, and playing of the game because “so many splendid men and women have recently crossed the vale which the faithful believe leads from life to life.” Playing the game allowed participants to communicate one last time with dear departed loved ones, allowing some solace. Many felt it selfish to call them back from a place of peace to offer words of comfort.

Ouija playing became an epidemic in the Southland, with the entertainment industry helping to explode it into the popular conscience once again. While papers noted it gave some comfort, others derided the game, calling it “a duplex hootinganic consisting of a sample of polished dance floor with an alphabetical frieze doll’s milking stool with green felt slippers and a heart-shaped seat,” of course claiming it didn’t work.

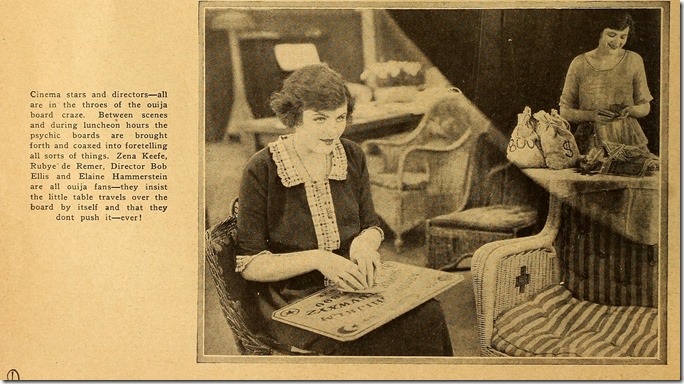

Many stars played the game for fun, happily posing for photos distributed to magazines and newspapers. Others took to it in hopes of divining their future in the often precarious industry. Many held parties to both entertain themselves and others by enjoying the game, while at the same time happy if it gave them hope of a promising future. Los Angeles Times columnist Grace Kingsley also claimed that the game’s popularity was also due to the fact of the material world taking the place of alcoholic spirits with the rise of Prohibition.

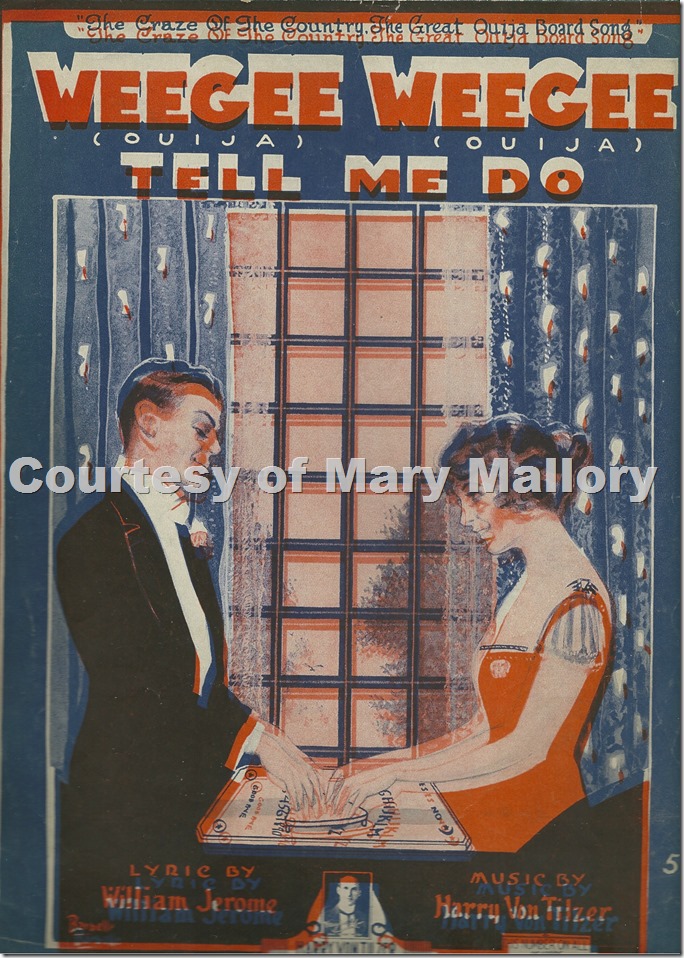

Early in January 1920, composers William Jerome and Harry Von Tilzer took advantage of the national craze for the game to create the first song about it, “Wee Gee, Wee Gee, Tell Me Do,” which soon became a major hit, which their publishing company, owned by Von Tilzer, called “The craze of the country, the Great Ouija Board Song.” The patter of the second verse stated, “This little board is the ruler of the nation now,” which appeared to be the case in many places. As with most things about the game, the song focused on women and their uses for the board, with the second chorus going, “Wee Gee, Wee Gee Tell me do, Are the men you marry girlies always true? Should the supper table wait for the ones who really love to come home late.”

The January 21, 1920 New York Clipper called it a cleverly written song. Many vaudeville and minstrel performers quickly added it to their acts, including top stars Marie Cahill and Lew Dockstader. “Wee Gee, Wee Gee..” led all sales for sheet music the week of June 5, 1920 as well.

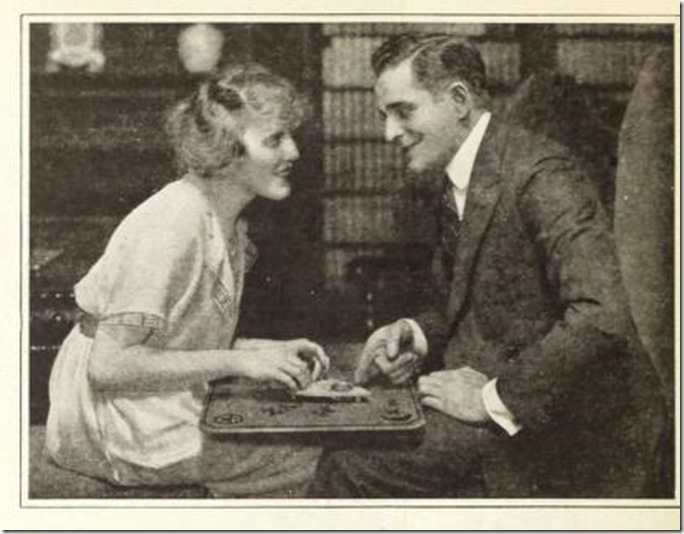

Crane Wilbur and Ruth Hammond in “The Ouija Board.”

The craze took off in other forms of entertainment as well, with the one-act play “Ask Ouija” and and Crane Wilbur’s successful play “The Ouija Board” employing it as both title and theme. Reviews called “The Ouija Board” a thriller about spiritualism, in which “real spooks invade a fake seance, leading to a murder mystery and suspense.

Newspapers and magazines employed it as a way to talk about possible future events, with the Motion Picture Herald titling a column, “Reading the Ouija Board” and others asking, Ouija, Ouija, Tell Me Do” in stories about sports, weather, and games of chance. Cartoon characters Mutt and Jeff consulted the Ouija in several strips as well.

Ouija dominated films that year as well. Writer Frances Marion adapted the short story, “the Manifestation of Henry Orth,” a satirical comedy about actions happening around the Ouija Board for the screen. Max Fleischer’s KoKo the Clown featured a spooky Ouija. Doug Fairbanks even employed a Ouija in his film, “When the Clouds Roll By.”

The first to actually feature the game both prominently in the title and story was the Cohn Brothers’ Hall Room Boys comedy, “Tell Us, Ouija,” in which Neely Edwards and Hugh Fay join in consultation with spirits “to put up a front without any financial backing,” long before Mel Brooks’ “The Producers.” Film Daily considered them wise to acknowledge such an important fad, with comedy sure to please and earn nice returns.

By late 1921, the Ouija fad began fading, but the game ended up in the Supreme Court in 1922 when the new trademark owner, the Baltimore Talking Board Company appealed a Federal Court decision which agreed with the government’s classification of the game as sporting goods, thereby making its profits taxable. The Supreme Court refused to hear the case, and the lower court decision stood.

The Ouija Board is still around today, though not as popular as in past decades, thanks to frenetic and colorful video and computer games replacing it in popularity. Though what many would consider old-fashioned, the game will never entirely go away, as many people look for ways to divine their future or bring good tidings into their lives.

Houdini, who relentlessly exposed fake spiritualists, must have said something about this fad

LikeLike

In the early fifties my mother played around with the board. One day it told her “Bobby dead”,shortly after my brother, who was in the Navy, was hitch hiking home from was killed by a car. She never used that board again. Whether it was some supernatural power or something that was on her mind with his absence I don’t know.

LikeLike