Jan. 6, 1924: The Times publishes a photo of an Oakland car that was driven up to the Hollywood sign.

Southern California and Los Angeles exploded into the public zeitgeist thanks to imaginative advertising and publicity from area supporters and officials. Posters, postcards, and lavish illustrations in magazines and newspapers touting glorious weather, abundant land, and great opportunities started the great march westward.

Later, real estate developments around the Los Angeles area like Hollywoodland that successfully promoted themselves as exclusive, elegant, and close to business centers prospered, thanks to creative advertising gimmicks by salesmen. Leland J. Burrud excelled in innovating practices and developing schemes to sell real estate, from bringing in newsreel cameras to record the construction of the Hollywoodland Sign in November 1923 to creating dramatic images of a car posing adjacent to the Sign. He developed his great talent from his multi-faceted film career traveling the American West in the late 1910s and early 1920s.

Mary Mallory’s “Hollywood land: Tales Lost and Found” is available for the Kindle.

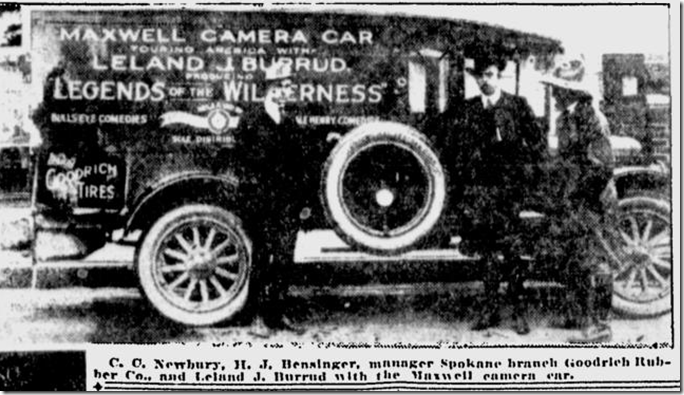

The Maxwell Camera Car in the Spokesman-Review, Nov. 2, 1919.

Born in Newark, New Jersey December 2, 1889, young Burrud followed his passion upon graduating from high school. Heading the local advertising department for the Newark Union-Gazette after graduation in 1908, Burrud resigned and left for sunny Southern California in 1910 when he landed a job working for Eastman Kodak in Los Angeles, per the October 6, 1910 Monroe County Mail. Thus began his filmmaking odyssey across the American Southwest.

Burrud remained in the Los Angeles area for two years before moving to El Paso, Texas, the birthplace and home of his wife Jane, where he worked as a newsreel photographer for the Fred Feldman Company, according to the July 13, 1915 El Paso Herald. The paper reported he was “making movies and still pictures of the crowds in the Plaza,” which would later be exhibited in local and national theatres. These actualities captured local residents in their daily lives, later promoted in newspapers suggesting “Come see yourself onscreen.” At the same time, Burrud led the local ad club, making short films that were exhibited in Chicago, Illnois at the national advertising convention.

“Movie man” Burrud explained the art of advertising in speeches to local organizations, promoting the concept of striking images and strong ad copy and graphic layouts in various forms of media to attract attention and eyeballs in order to create sales. Burrud stated, “The only force that ever sells anyone anything is the planing and developing in the purchaser’s mind that he will benefit by the transaction, so we find that the true reason for advertising is to convince someone that he needs of or desires what ever you are offering for sale.”

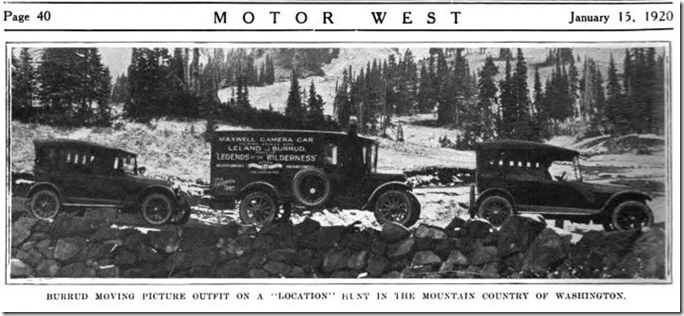

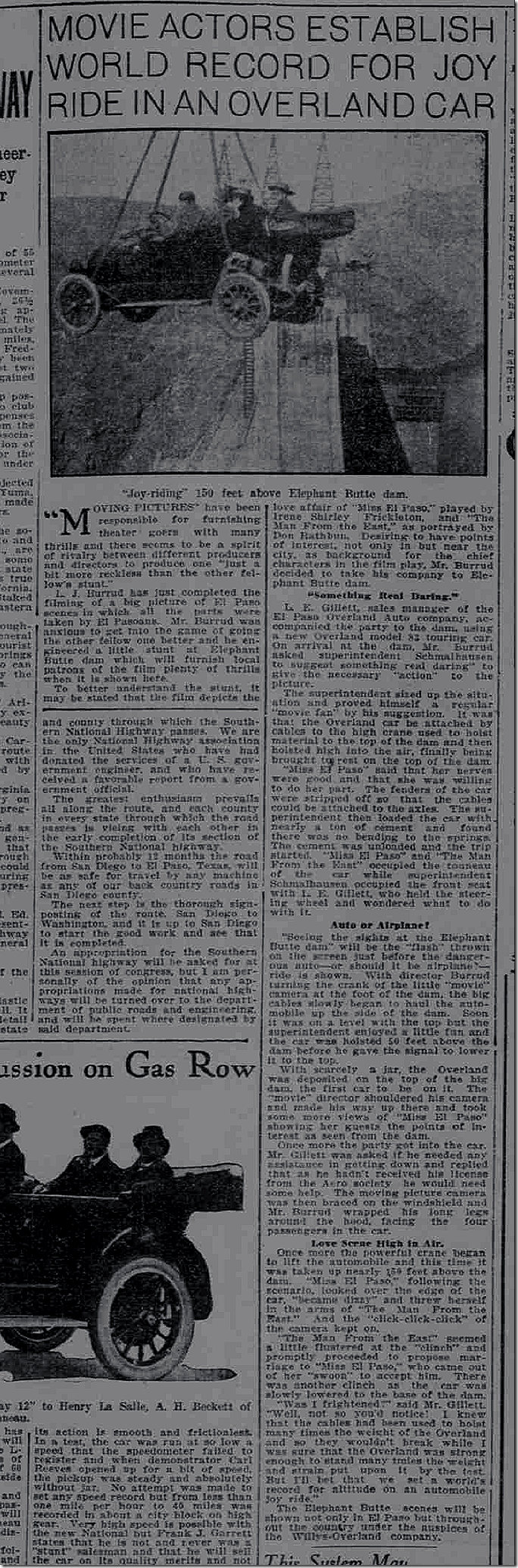

Exploring Washington, in Motor West.

In October 1915, Burrud resigned from the the Feldman Company, planning to make short films displaying El Paso’s top attractions in order to promote it to communities and businesses outside the area. He convinced the local Chamber of Commerce to help fund what became the feature, “The Romance of El Paso,” starring locals and a few real actors in a fictional story of a young man visiting his love in her home town of El Paso, in which they toured the city’s leading tourist attractions and highlights. Burrud gained news blurbs throughout the making of the film, but hit the jackpot when the January 22, 1916 El Paso Herald printed the compelling photo of a giant crane dam lifting an automobile containing his stars and El Paso mayor onto the top of the Elephant Butte dam. The film later played to good reviews in El Paso as well as Albuquerque, New Mexico.

In October 1915, Burrud resigned from the the Feldman Company, planning to make short films displaying El Paso’s top attractions in order to promote it to communities and businesses outside the area. He convinced the local Chamber of Commerce to help fund what became the feature, “The Romance of El Paso,” starring locals and a few real actors in a fictional story of a young man visiting his love in her home town of El Paso, in which they toured the city’s leading tourist attractions and highlights. Burrud gained news blurbs throughout the making of the film, but hit the jackpot when the January 22, 1916 El Paso Herald printed the compelling photo of a giant crane dam lifting an automobile containing his stars and El Paso mayor onto the top of the Elephant Butte dam. The film later played to good reviews in El Paso as well as Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Burrud became a newsreel photographer for Pathe in 1916, shooting “Mutual Weekly” newsreel footage in Texas, Mexico, and New Mexico, making 500-800 feet rolls of locations as part of their “See America First” series. He even captured images of Fort Bliss, Mexican generals Juarez and Pancho Villa, and skirmishes in Columbus, New Mexico which were exhibited across the country. After a few months witnessing carnage and destruction, Burrud joined the Fox Film Company in its failed effort to film an eight reel feature in and around El Paso.

Finally in 1917, Burrud seemed to find his calling: creating advertising promoting products. Papers noted on July 25, 1917 that Burrud shot a “Motor” Pictorial short in which he drove a Dort automobile to the top of Zion Canyon in mid-November 1917, gaining lots of press coverage. The young man smartly gained automobile sponsors through catchy news blurbs announcing great feats of endurance, reliability, and safety of automobiles in scaling mountains, surviving icy roads, and traversing deserts.

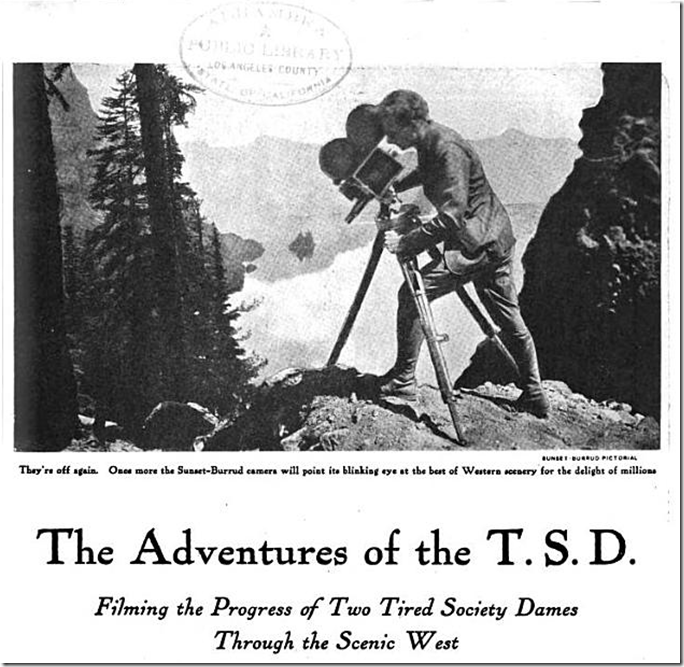

Burrud and family returned to Los Angeles in 1919 to create a series of “scenic” films displaying the beauty and majesty of the West. Motion Picture News reported on August 23, 1919 that Burrud was traveling 20,000 miles throughout the West to produce one reel “Legends of the Wilderness” series in partnership with Sunset Magazine in a company called Sunset-Burrud Pictorial Co., producing films based on stories than originally appeared in the magazine, an early form of cross promotion. These films would be sold on a states rights’ business by Bull’s Eye Film Corporation. At the same time, Burrud often shot striking photographs that would run in the magazine, displaying some of the gorgeous countryside visited.

Burrud’s Moving Picture Outfit consisted of a Maxwell truck and car which carried his crew and equipment along miles of unpaved or newly created roads. The article mentioned that Burrud and his small staff had recently returned from the Pacific Northwest. While there, Burrud started shooting “Trail of Glory” on October 3, 1919 using Whitman College students to tell the Marcus Whitman story. College President S. B. L. Penrose endorsed and assisted him in producing the film, per the Walla Walla Bulletin.

Each of the one-reel shorts promoted scenic locations across the West, suggesting that residents “See America First” when traveling. Burrud obtained sponsors like Maxwell and Goodrich tires to help defray costs, giving them free advertising in stories mentioning the reliability and quality of their products, and by plastering their names on the side of the automobiles. Many of the shorts also featured two attractive young women supposedly traveling through gorgeous countryside, places like Yosemite, Yellowstone, the Grand Tetons, The Painted Desert, the Grand Canyon, the Pacific Northwest, God Country. Many of these were shot in a form of color known as Polychrome, featuring toning and tints.

Some of the titles in the series included “The Weaver of Dreams,” “The Desert’s Spring Song,” “Dream of the Sea,” “Snow-Bound Yosemite,” “Beauty Land,” “The First People,” “The Wilderness,” and “The Ranger.” Moving Picture Age noted the beauty of “The Ranger” and its photogenic capturings of rushing torrents, rapids, and moving clouds. Educational Screen in early 1923 called “The Dream of the Sea” “a poem in polychrome coloring,” employing John Greenleaf Whittier poem lines as titles, in a short displaying the unfolding beauty of the sea. The February 1923 issue of Education Screen revised “The First People,” stating, “The sum total is a dignified and beautiful program picture, showing members of the Vanquished Race still clinging to their former customs and traditions.”

By 1922, as the run began slowing down, Burrud began taking freelance photographs on the side, which sometimes appeared in the Los Angeles Times and magazines like Arrowhead or pictorials like “The Heart of California.” Later than year, he became advertising manager for Lake Arrowhead, writing attention-grabbing copy and making lovely pictorial images of the area, shared in magazines and newspapers. A few of these photos showed him with Los Angeles advertising man, John Roche, who would go on to design the Hollywoodland Sign just a year later.

The El Paso Herald, Jan. 22, 1916.

Real estate promoter S. H. (Sidney) Woodruff noticed his work, hiring him as Hollywoodland’’s advertising manager on September 7, 1923. Once hired, Burrud took photos, wrote copy, and devised ingenious publicity gimmicks to gain attention for the tract. Besides writing copy and taking photographs, Burrud created a stunning color brochure of the development, announcing its special amenities. He shot a two-reel film capturing the construction of the tract’s demonstration house, exhibited at a national real estate convention in 1924. After John Roche created an eye-catching design for a large scale billboard promoting the development, Burrud arranged for the Fox Movietone newsreel photographer to shoot construction of what became the Hollywoodland Sign, which arrived at the Fox Movietone headquarters at the end of November 1923. Within a few weeks, copying some of his own earlier stunts, he arranged for an Oakland touring car to ascend the hill, gaining publicity both for the development and the car company by posing it adjacent to the Sign after its stunt. Burrud later organized the Hollywoodland Community Orchestra in 1924, which played during its own thirty minute radio show on KHJ radio for over a year.

During the next several years, he continued writing copy and making photos of the development, some of which appeared credited in the LA Times, as well as serving as Director of Advertising for the Greater Los Angeles Assocation. Burrud later served as Woodruff’s publicity director for his new development at Dana Point beginning in 1927. He even lectured on the use of advertising and publicity in real estate at Loyola in 1929.

In the 1930s, Burrud moved on to become sales director for Capital Company, heading up advertising for their upscale developments Los Feliz Terrace, Glendale’s Montecito Park, Culver City Park, Brentwood Highlands, Beverly Square, Sherman Oaks’ Independence Square, Valley Vista, San Clemente, and Laguna Beach. During this same time, his son Bill Burrud appeared in motion pictures, before later going on to produce his own series of animal and travel documentaries.

In 1939, Burrud was named Vice President of the Hearst Corporation’s Sunical Land and Packing Company, the real estate arm of the corporation, where he worked for almost 20 years. L. J. Burrud passed away December 13, 1959, leaving behind a rich legacy of film work documenting the American West, automobiles, and real estate development. Though forgotten today, his creative use of advertising and publicity started the branding of the Hollywood Sign to the United States and later the world, where it stands as a metaphor for climbing the road to success in Hollywood.

There were Bill Burrud travel adventures on TV back in the day

LikeLike

It’s fun learning about Bill Burrud’s father, the Huell Howser of his day. Heck, even Bill Burrud is pretty much forgotten now. Whatever happened to all those movies?

LikeLike

I tried contacting the grandson through the old Burrud website, he created reality show, I need to try again. I guess filmmaking was part of the family.

LikeLike

L.J. Burrud was born in Newark, N.Y., not New Jersey. His father was in the mincemeat and cigar business.

LikeLike