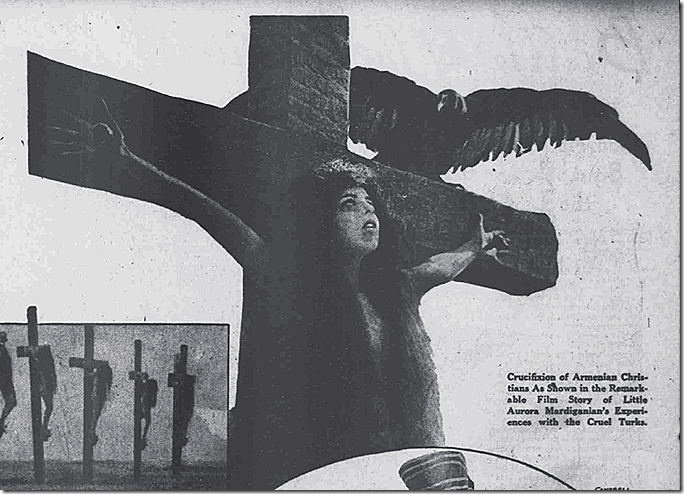

A still from “Auction of Souls,” in the Washington Times.

For more than 120 years, Armenians have seen slaughter and death at the hands of the Ottoman Empire and the Turks. In 1894, Sultan Abdul-Hamid II ordered the first massacre and harassment of the Armenian population, with more than 300,000 people killed over three years. 30,000 Armenians were killed in 1909 when Turks in Cilicila revolted against Armenian democratization efforts. In 1915, the wholesale slaughter of Armenians began as a result of World War I, when Armenia became separated from the Allied Forces which supported it when Turkey sided with Germany. As Tony Slide reveals in his book, “Ravished Armenia and the Story of Aurora Mardiganian,” Russia invaded Turkey and British and French forces attacked Constantinople, precipitating disaster. On April 23-24, 1915, Turkish police began rounding up 800 leading Armenians in Constantinople, exiling them, and began widespread extermination of the Armenian population on April 24. This year marks the Centennial of the Twentieth Century’s first massive genocide, in which more than one million Armenians were slaughtered, half of the population at the time.

One young Christian girl, Arshalouys Mardigian “Aurora Mardiganian,” suffered horrific experiences during the genocide but survived and escaped to America. Her story of a young girl suffering abuses and ravages came to stand for that of Armenia itself when her book, “Ravished Armenia,” was released in 1918. Mardiganian herself starred later that year in a movie adaptation called “Ravished Armenia,” later changed to “Auction of Souls.” In many ways, Mardiganian represents her ravished homeland, as she was exploited and abused by the very individuals who were supposed to provide help, becoming a bit player in her own story. Her story helped publicize the widespread genocide and diaspora of her people, vividly personified in what little remains of the powerful film.

Mary Mallory’s “Hollywood land: Tales Lost and Found” is available for the Kindle.

And ad for “Auction of Souls” in the Times-Republican of Marshalltown, Iowa.

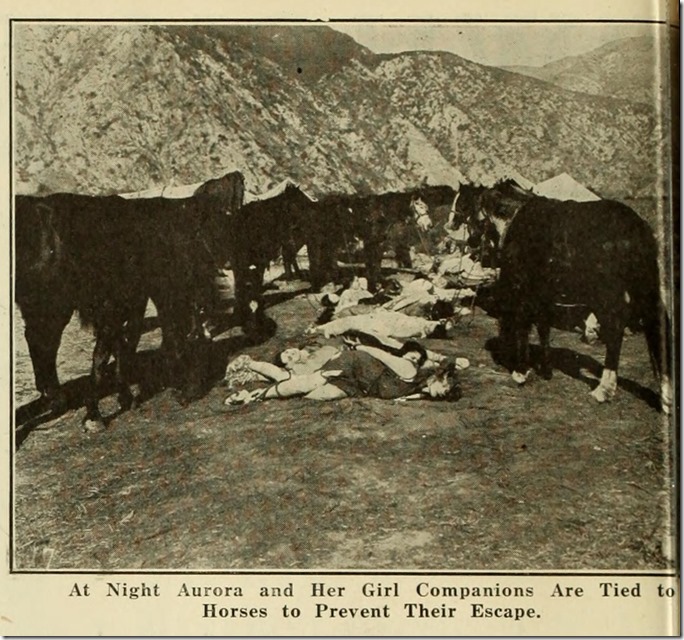

On Easter Sunday in April 1915, Turks entered the city of Tchemesh-Gedsak, the home of the Mardigian family, demanding that the Christians recognize Mohammed and convert to Islam or be led away. Ethnic cleansing began. Men and boys were separated from women and children, while news of atrocities and massacres spread. Many were led away to be beaten, tortured, and savagely murdered. Others were led on slow, agonizing death marches to the desert. Many women and girls were ravaged and raped. Mardiganian witnessed the murder of her entire family except for an older brother and sister who survived. A younger brother and sister were clubbed to death by a Turkish soldier using a whip handle, another soldier threw her youngest sister over a cliff to her death, her six-year-old brother was stabbed to death in front of her, her 15-year-old brother was killed in a Turkish prison, her mother was whipped to death at her feet, and her 16-year-old sister was stabbed to death cradled in her arms. Mardiganian survived many things over more than two years; a march of more than fourteen hundred miles before being sold into slavery and a harem, from which she escaped and came to America, searching for her few surviving relatives.

She arrived in the United States at Ellis Island, November 5, 1917 per Slide, where she was supposed to be adopted by a Boston family. Instead, an Armenian family in New York took her in and helped her place newspaper advertisements looking for her oldest brother. She was interviewed by New York newspapers as a result of the ads, coming to the attention of Harvey and Eleanor Gates. Gates, a screenwriter, with later credits such as “If I Had a Million” (1932), “The Lives of a Bengal Lancer” (1935), and “The Courageous Dr. Christian” (1939), had her guardian family interpret her words as he transcribed her story into the book, “Ravished Armenia,” in conjunction with the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief. Mr. and Mrs. Gates changed her name from Arshalouys (“Light of the early morning”) to Aurora, and her last name from Mardigian to Mardiganian, telling her that they were going to take care of everything for her and her people. Young college dropout Nora Waln, a secretary for the American Committee was her guardian. Aurora was sent to a Connecticut convent for three weeks to learn some rudimentary English. Newspapers in New York, Washington D. C., and other places serialized the book for months, building widespread interest in the abject destruction of the Armenian people.

When she returned, the Gates had her sign some papers, which they claimed would allow her to come to Los Angeles and have her picture taken. Aurora assumed that still photographs would be taken, but in fact, it was a contract for the filming of the motion picture, “Ravished Armenia,” in which she would star and receiver $15 a week. When interviewed by Slide decades later, Mardiganian stated that knew virtually no English and that the Gates told her that $15 was a lot of money, so she naively signed the contract.

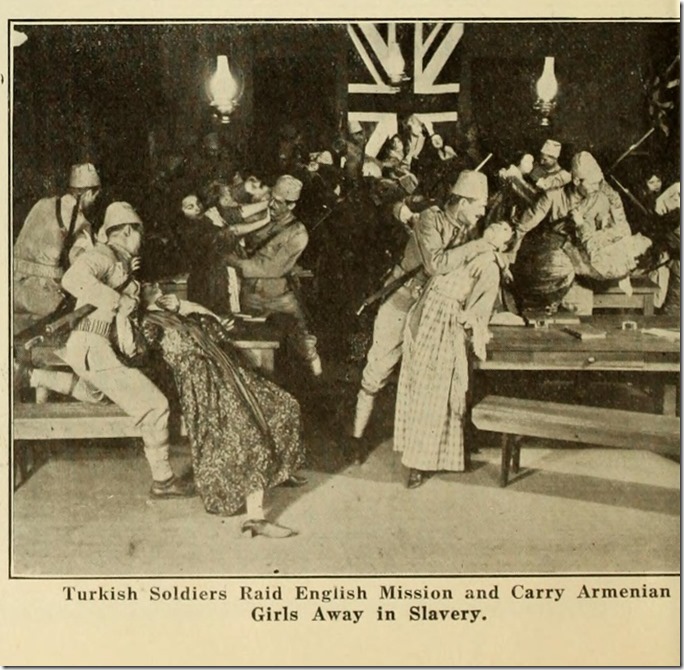

A still from “Auction of Souls” from Moving Picture World.

Col. William N. Selig bought the rights to the book, with the script credited to Nora Waln in publicity materials, but with actual copies of the script listing Frederic Chapin as author. Oscar Apfel, a veteran film director, and Cecil B. DeMille’s co-director for “The Squaw Man” in 1914, was signed to helm the First National Release. As the December 7, 1918 Moving Picture World stated, “Aurora Mardiganian, an Armenian girl, who admits that she cannot act, but that she can dance, is to play a leading part in H. L. Gates story, “Ravished Armenia,” soon to be filmed at Selig Studios under the direction of Oscar Apfel.”

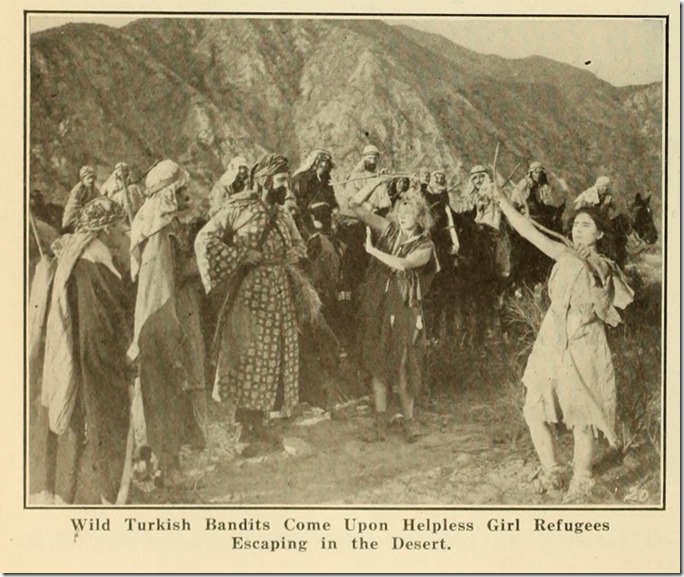

The sensitive Maridiganian began reliving her mind-numbing experiences in her onscreen role, a heavy burden for one who endured horrible atrocities. Two weeks later, during filming of a scene in which she crawled through a second story window to make an escape, Mardiganian fell 15 feet to the ground breaking either one or both of her ankles, though the papers stated she only severely bruised one ankle. Mardiganian, realizing the importance of the production, claimed that the injury was fine and continued filming on adrenalin, only to collapse upon completion of the picture. Desert scenes were filmed in the dry bed of what trade papers called “the San Fernando River near Newhall,” with many local Armenians hired as extras.

Produced to coincide with a November 29, 1918 Presidential proclamation urging Americans to donate to a $30 million fund benefiting homeless and stricken Armenians, “Ravished Armenia” took only a month to complete, featuring such American stars at the time as Anna Q. Nilsson, Irving Cummings, and Eugenie Besserer. as it documented the Turkish atrocities while also somewhat exploiting the sexual degradation and exploitation of the Armenian women. Director Apfel later told the Morning Telegraph, “This picture stands as a monument of truth—its cry is far-reaching and nothing that is true should be too horrible to depict.” Music cue 24 for the film was even called, “It is a real extermination.” Incredibly realistic for its time, the film still changed some scenes considered too brutal for audiences, showing the crucifixion of girls on crosses rather than the actual images of them impaled on swords and sabers.

The Los Angeles Times reported on January 9, 1919, that Mayor Frederic T. Woodman of Los Angeles hosted a luncheon for Mardiganian at the Alexandria Hotel January 8, followed by a reception that night in the ballroom by his committee of One Thousand for Armenian Relief. Mardiganian spoke to the attendees in broken English, thanking them for coming and supporting the cause., noting that her story was told by Gates in support of the National Committee for Armenian-Syrian Relief, with Mr. Gates personally supervising the film. This audience would attend a private screening of the $500,000 film “Ravished Armenia” January 15 in the Alexandria ballroom, before public showings on January 19 at the Majestic. These early screenings around the country for society and cultural leaders cost $10 a ticket, with the funds dedicated to Armenian Relief.

The title was quickly changed to “Auction of Souls,” possibly to appease censors and prudes, and possibly to appeal those who saw Christians being persecuted by Muslims. Its vivid illustrations brought to dramatic life world and news issues on the big screen, searing them into the public imagination.

Some state and city censorship boards in places such as Massachusetts, Kansas, Pennsylvania, Georgia, Atlanta, and Detroit prevented those under the age of eighteen or twenty one to attend the film, and attempted to ban screenings for its violence and brutality, all overturned by court order or police officials. Judge G. L. Bell of the Supreme Court of Georgia issued an injunction June 27, 1919 restraining Atlanta from preventing screenings, stating, “The picture seems to me to be an appeal to Christianity to rise up against the crimes of the Turks…It is merely a portrayal on the screen of the things we read of every day in print.” He noted that evil was not displayed attractively in the production.

A still from “Auction of Souls.”

The Exhibitors Herald wrote in May 1919 that the film exceeded expectations. “It is an offering for the serious-minded and the thoughtful,” “never vulgar or obscene,” but “it is a picturization of one of the saddest pages of modern history.” Motion Picture News reprinted an article by Mrs. Oliver Harriman from Harper’s Bazaar which stated that the film showed “the annihilation of Armenia,” a “burning indictment of those who are responsible for

Armenia’s woes, “ showing the “efforts of the Turks toward the entire extermination of her people.”

Film Daily’s June 1, 1919 review called it “Sensational in the extreme: propaganda against Turkish barbarism in Armenia in its most forceful form.” Apfel’s incredibly powerful and intense film appeared almost as realistic documentary footage in its depictions of massacres, death marches, atrocities, and sexual degradation, offering attractions both to the high-minded and those seeking out sensationalism.

Moving Picture World stated that it was “so reverently done and so wonderfully true to humanity in all that it shows, that no doubt it will be kept for years and handed down as historic manuscript in picture.”

While newspapers and trade heralds lauded the picture, fan magazines excoriated it. Frederick James Smith in the August 1919 issue of Motion Picture Classic stated, “…the cheap sensationalism of its advertising panders to the worst of humanity. We are heartily sick of the screen’s exploitation of atrocities under any guise. And atrocities are as thick as cooties in “Auction of Souls.” Miss Mardiganian isn’t camera interesting.”

Aurora made appearances across the country in support of the film, often making morning appearances at women only screenings, and then appearances for mixed audiences at night. The Detroit paper claimed she addressed a crowd of 2000 enthusiastic Armenians in her native language at the film’s premiere in that city on the first anniversary of the Armenian Republic. The Gates gained great press coverage as well, interviewed in several places and making speeches as well on the film and what Aurora hoped to accomplish with it and her appeal to Americans.

Aurora herself began having problems dealing with the new experiences and emotions thrown upon her in social situations, feeling alone and isolated even though accompanied by a chaperone, Mrs. J. P. (Mary) Anderson. More public appearances were requested than she could handle. Mardiganian made her final personal appearance with the film during its Buffalo, New York premiere either on May 10 or 12, 1920, before Mrs. Gates sent her to a convent girl and hired seven lookalikes to take her place at appearances. Aurora threatened suicide and ran way to New York, getting in contact with Mrs. Harriman.

A still from “Auction of Souls.”

The Butte Daily Bulletin reported August 17, 1920 on a July 25, 1920 letter written by Aurora to her brother, noting that she wasn’t well and no longer working with any film company, which gave her difficulties. It also stated, “All the money I had, my guardian Mr. Gates and his wife, robbed, and now they persecute me because I demanded my rights.” She claimed that the film company robbed her of her name, saying they found another Armenian to play her onstage. Aurora claimed the Gates locked her in a room for three days until she signed away all her rights.

Mardiganian sued her guardians in February 1921 for an accounting of the monies related to the film and book. The Gates revealed that Mardiganian had been paid $7,000 to appear with the film, but the cost for Mrs. Gates’ services, a chauffeur, nurse, and seven lookalikes cost $6,805, leaving Aurora only $195. She did eventually receive $4,500. In the late 1920s, a New York law firm approached First National on her behalf for an accounting of fees owed her for personal appearances promoting the film, for which they claimed no indebtedness. Poor Aurora once again suffered indignities under those who should have protected her.

The film disappeared within decades and was considered lost. In the last twenty years, Slide was contacted by someone claiming to have twenty minutes of “Auction of Souls.” He discovered that only bits and pieces of the action sequences of the film were cut into a documentary about the Armenian genocide. Slide writes that Apfel “has obviously created a film with such a documentary-like feel that it is almost cinema verite. It is actuality rather than a staged narrative. The realism is intense, and it is unimportant what the shots or scenes are meant to represent because the drama, the tragedy, the momentum, is all here. It is instant and it is virtually real.”

In 1929, Aurora eventually married and had a son, Martin. She disappeared for years. When Slide began working on his book in 1988, he became fascinated with her. Through an Armenian organization, he was able to track her down, finding she lived alone in Van Nuys. He met her in the tiny one-room apartment where she lived in fear Turks would come and kill her. Slide audiotapes the interview, noting how tragic that this resilient survivor could recall the horrible experiences of being harassed, exploited, and ravaged by so many, both in Armenia and here in the United States. He lost track of her and never met her again, but discovered she died at the age of 92 in a San Fernando Valley nursing home, all alone. Her ashes were unclaimed, and she was eventually buried in a pauper’s grave.

Her story stands as witness to the terrible atrocities suffered by the Armenian people, who saw their country destroyed and their people annihilated. They endure the refusal of governments in Italy, the United States, and other counties to utter the word genocide in regards the destruction of their people in order not to upset Turkey, on which they rely for military support in the Middle East. May on this upcoming terrible anniversary Centennial of the Armenian diaspora, that the word genocide be rightfully acknowledged for the atrocities committed against the Armenian people.

I’ve always been fascinated by Aurora Mardiganian’s story, and revolted by the Armenian genocide. I wonder if there is any estimate of how much money was donated to the relief cause as a result of film screenings? It is such a shame that her protectors exploited her so, during and after the filming! Still, in spite of it all, she accomplished a tremendous amount in her goal to help her people and bring knowledge of this atrocity to the wider world!

LikeLike

Wow. I wish I could see this film.

LikeLike

What an amazing story! How terribly sad for all the Armenians who suffered, and how shameful for the treatment Aurora received here in the United States. Thank you for taking the time to write this entire narrative and include the images from the film. I wish more people would read this than (I fear) ever will.

LikeLike

May God comfort her in His Bosom and bless her soul.

LikeLike

This poor woman. What an amazing story. I want to see whatever remains of this film!

LikeLike

Here she was interviewed

https://sfi.usc.edu/video/day-14-30-days-testimony-anthony-silde-aurora-mardiganian

LikeLike