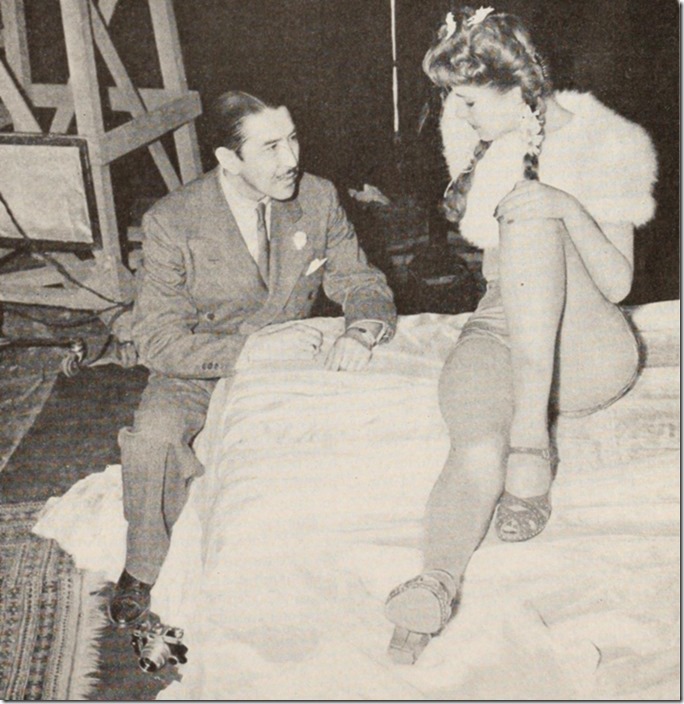

Vargas poses with Kay Aldridge in a photo published in Cine-Mundial.

“One day I will paint a Vargas girl so beautiful, so perfect, so typical of the American Girl, that I shall be able to show it to people anywhere in the world, without my signature on it and they’ll say, that’s a Vargas girl!” — Alberto Vargas quoted in “Vargas” by Taschen.

Although some people might not know his name, many recognize the curvy, overly endowed model drawings designed by illustrator Alberto Vargas in the latter half of his career. Drawn for Esquire and Playboy magazines, these luscious line drawings of sexy yet innocent young women attracted great attention, and cemented his name in the national conscience.

Born Joaquin Alberto Vargas y Chavez in Arequipa, Peru, to wealthy parents, young Vargas showed deep interest in art from an early age. Drawing caricatures from the age of 7, before moving on to landscapes and portraits in his teens, Vargas was inspired by his famous photographer father to follow his dreams. His mother sent him and his brother to Zurich, Switzerland, in 1914 for a quality education in photography and languages, but Vargas soon traveled Europe after taking up painting. A natural autodidact, the young artist studiously visited galleries and museums, learning technique and form.

Mary Mallory’s “Hollywoodland: Tales Lost and Found” is available for the Kindle.

In October 1916, Vargas immigrated to New York City, and sold his first freelance artwork in late 1917 for a few dollars. As his portfolio grew, so did his payments, and he switched to working in watercolors. By the late teens, he was creating freelance artwork for a variety of New York magazines and newspapers glorifying the young American girl, influenced by the artist Raphael Kirchner. The June 20, 1919, New York Tribune called him a “talented young artist…recently returned from his studies in Paris, his work shows the influence of the best French school, delicate in handling, painstaking in detail… .”

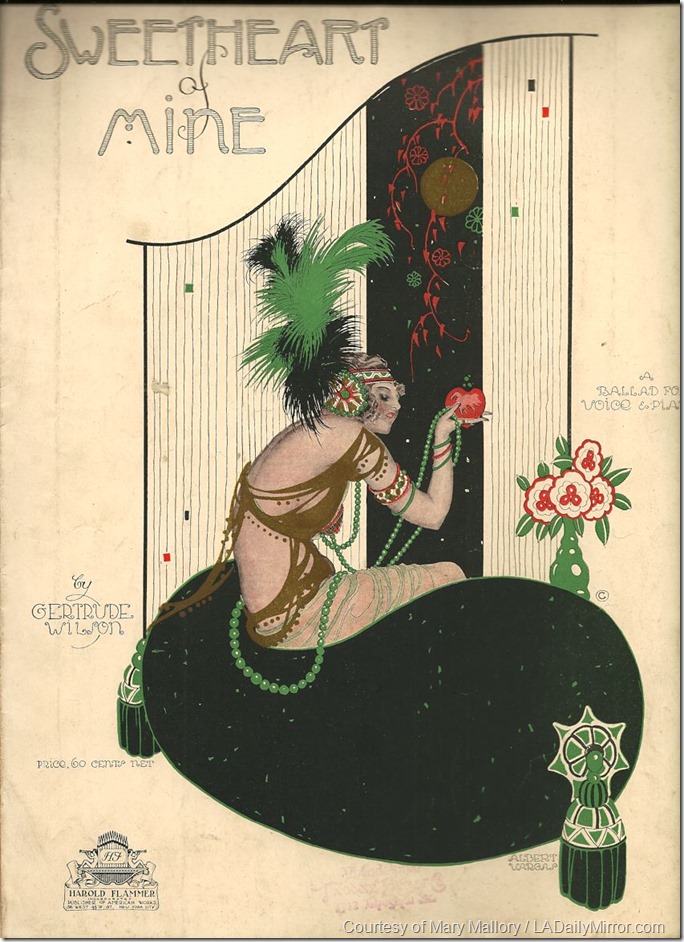

Not only did Vargas draw for magazines or newspapers, he also designed covers for sheet music. In 1920, he sketched the art nouveau cover of “Sweetheart of Mine,” with a scantily clad showgirl offering a gift of temptation, all delicate lines and suggestive nature. It demonstrated his exclusive focus on drawing luscious and tempting women for publication. He also drew beautiful portraits of female screen stars for publications, starting with copying a photograph of Norma Talmadge, “The Branded Woman,” for the cover of Theatre magazine in February 1920.

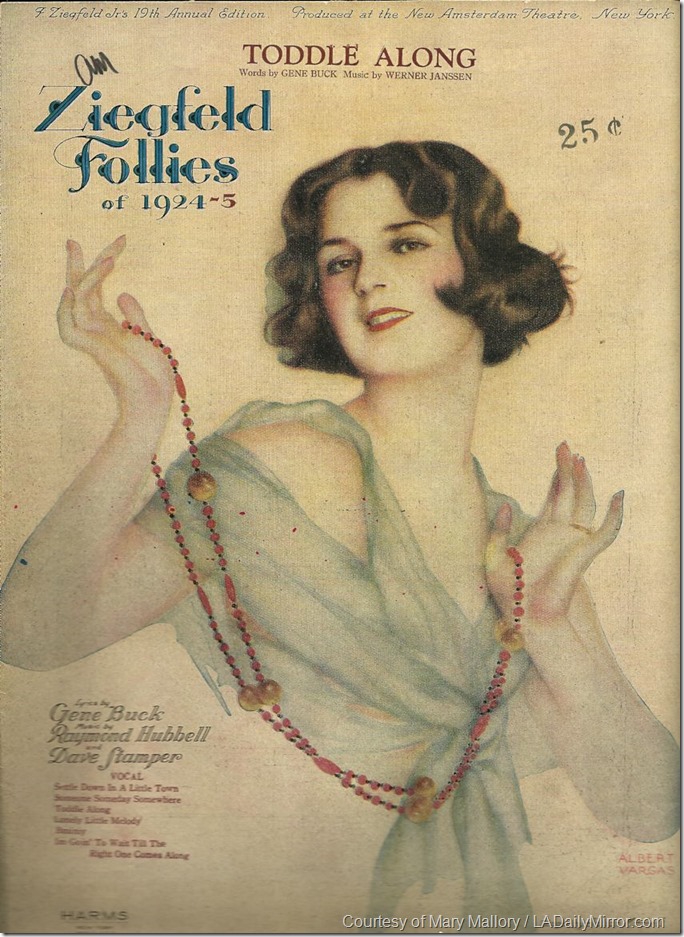

Vargas landed his big break when theater impresario Florenz Ziegfeld discovered him in a Corona Typewriter store window painting portraits of a model for the noontime crowd, and quickly signed him to a contract of first call in 1920 to create a series of gorgeous 30 x 40 inch watercolor portraits of his Follies’ headliners that hung in the New Amsterdam Theatre lobby. Over the next 12 years, Vargas worked his way through master showman Ziegfeld’s stars and showgirls, starting with Ziegfeld favorite Marilyn Miller, as well as Fanny Brice, Eddie Cantor, W.C. Fields, Olive Thomas, Paulette Goddard and Gilda Gray. He also designed some ethereal sheet music covers extolling some of the young beauties. His portraits of showgirls wearing sheer fabrics clinging to the body offered just enough skin to suggest temptation. As Vargas would state over the years, Ziegfeld taught him the difference between “nude” and “lewd.”

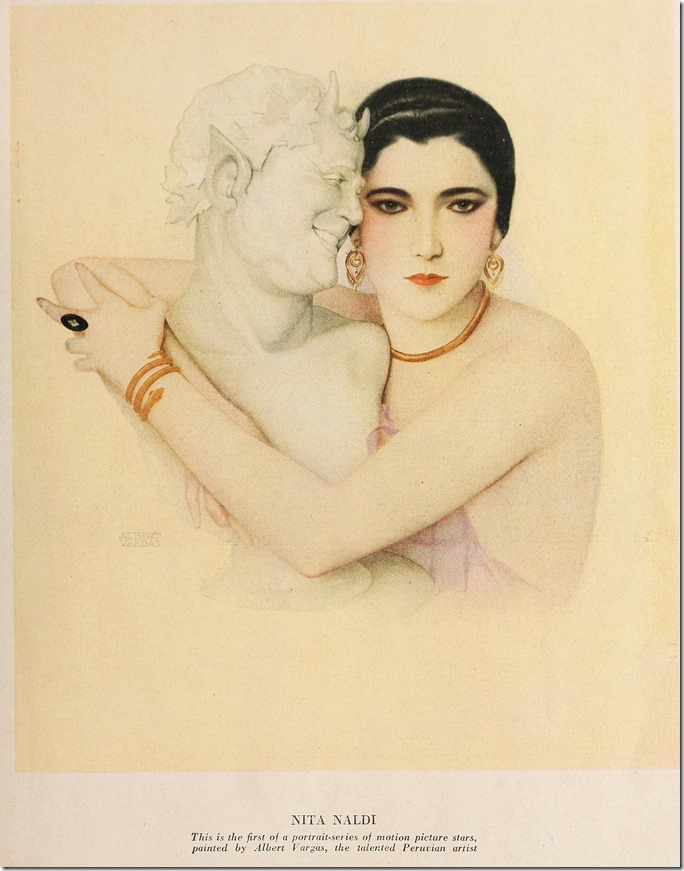

In 1922, Shadowland magazine announced that “young Peruvian artist,” Alberto Vargas, “whose work is well known in South America through issues of Plus Ultra and Artes Grafias has drawn an exquisite series of motion picture stars for Shadowland.” Starting in March 1922, full-color reproductions of his portraits of such stars as Doris Kenyon, Norma Talmadge, Alma Rubens and Lila Lee would appear, starting with voluptuous vamp, Nita Naldi. Motion Picture magazine hired him to create sumptuous covers in 1924 and 1925.

Movie studios also came calling as early as 1922, with Exhibitors Trade Review describing the elaborate coloring and titling of the film “Notoriety” carrying over to its advertising campaign of artistic posters “unusually colored” and drawn by leading artist Vargas. Otis Lithographic Co. was working to make the paper punch with color, to carry out the classy and high-brow look designed by Vargas. In 1923, journals noted that producers Weber and North hired Vargas to create posters, paintings, lobby cards, and scene cuts for the film, “Marriage Morals.”

The artist crafted his works from photographs and from his one steady model of the period, Anna Mae Clift. Vargas spotted the saucy Tennessee redhead in a New York crowd one day in 1919 and followed her down the street. He soon convinced the young woman to model for him, and quickly fell in love with her. Clift realized his devotion, but continued partying and seeing other men, believing him too much a gentleman, as he neither smoked nor drank nor fooled around. After 10 years, when the man she was seeing asked her to marry him, she concluded that she really loved Vargas. Upon revealing her love, the couple quickly committed to each other and married soon thereafter in 1930, a 10-year courtship, becoming virtually inseparable. His wife functioned as Vargas’ muse and partner until her death in 1975, always there as he sketched his models.

While he turned out work for a variety of media in the mid-1920s, Vargas switched from watercolors to oils, and began to make more and more use of airbrushing to achieve his sensual look.

After Ziegfeld’s death in 1932, Vargas first drew for Theatre, Tatler and Dance magazines and created hairstyle illustrations for Harper’s Bazaar, before moving his attention to Hollywood. He and his wife traveled west, and he began designing posters and drawing set illustrations for Hollywood films. Vargas created the key art for the poster of the Barbara Stanwyck film, “Ladies They Talk About” before being signed to a contract by Fox Films in 1934, designing illustrated posters and sketches of stars like Alice Faye and John Boles. His drawing of a confident Shirley Temple still hangs on the commissary wall at the studio.

In the late 1930s, Vargas worked at both RKO and Warner Bros., drawing set designs for the Charles Laughton film, “The Hunchback of Notre Dame, as well as crafting designs for Warner Bros. production designer Anton Grot for the Errol Flynn films “The Sea Hawk” and “The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex.”

Vargas’ politics were progressive and landed him in trouble in 1939, when he walked out due to threats of preventing unionization, and the studios blackballed him. The couple moved back East. Desperate for any type of work, Vargas churned out illustrations for Jantzen swimsuits, perfume bottles, middle class products.

Vargas was signed by Esquire magazine in 1940 and seemed to have it made. Besides drawing black and white illustrations of busty babes for the magazine, he continued drawing on the side. He produced illustrations for Hearst’s American Weekly and Jergens Co. as well as crafting a set of playing cards and a cheesecake calendar for the magazine, items that quickly sold out due to high demand from American G.I.s lusting after the leggy, busty drawings. Kurt Vonnegut Jr. wrote that, “What did these Vargas girls represent, whether they were supposed to or not?…They let us believe in sex as it can never really be — as easy and uncomplicated as falling off a log.” The United States Army sent him to bombardment schools around the country to create knockout mascots for any military unit that wanted one

For the next several years under the Esquire contract, everything seemed to go smoothly as the magazine quickly jumped in sales and Vargas’ saw nice salary increases, especially after the switch to color illustrations. The magazine changed the byline of his work to Varga, as the word had a better flow with “girl.”

Vargas resumed work at the film studios in 1946 after a disagreement with Esquire, designing posters and artwork for “Dubarry Was a Lady,” “Moon Over Miami,” and the like, also drawing Ava Gardner, Jane Russell, Ann Sheridan and Hedy Lamarr for Fawcett Publications’ Motion Picture magazine, before a lawsuit shut his work down.

In 1946, after some petty disagreements grew larger, Vargas sued the magazine, after realizing that it had snookered him into a deal by dropping in provisions into a contract, which he just glanced over, as he trusted in the magazine executive. The new contract, which paid him $18,000 a year, required him to churn out an image a week for 10 years, took ownership of the name “Varga,” and bound him to them exclusively until 1957. Vargas won in lower court, but lost in the Federal Court of Appeal.

Hopes for a movie called “The Varga Girl” produced by Harry Bloomfield and to have songs and score composed by E. Y. “Yip” Harburg died in 1948 after the magazine won the lawsuit on appeal.

Vargas and his wife scrambled to survive through 1956, with the artist designing perfume bottles, cigarette lighters, decanters and teenage products to stay afloat. Desperate for cash, Vargas traveled to Chicago in late 1956 to meet with Playboy publisher Hugh Hefner about drawing for the magazine. “El Hefe,” as Vargas called him, immediately realized what a sensation Vargas’ work would cause, as quoted in Vargas’ biography. “As soon as Hefner removed the first section of covering, I had the feeling that something lasting was about to begin. The work was exquisite.” By 1959, drawings by Vargas regularly appeared in the magazine, and once again, became a sensation.

His nude women became even more overt in their airbrushed sensuality, a teenage boy’s wet dream, with thrusting, upward breasts, long, swimming legs and erect nipples, which one writer called “risqué innocence.”

Once his wife died in 1975, Vargas stopped drawing for years, devastated at her death. Finally in the 1980s he began designing again, and prices of his art soared. In 1986, Vargas’ “Memory of Olive Thomas” sold at auction for $250,000, and his nude Nita Naldi sold for $300,000. His naughty nudes were now expensive collectibles. Vargas helped author a book on his life.

Alberto Vargas designed images of sexy, tempting women for the hot-blooded American male from the 1920s-1970s, work still highly prized. Ironically while he drew erotic art for the masses, he remained faithful to his devoted and loving wife, a gentleman to the end.

Thank you for bring Vargas to life. He comes across as a passionate, intelligent, and stylish artist.

LikeLike

Interesting shot of Kay Aldridge with Vargas. She eventually became “Queen of the Serials’ at Republic Studios, doing cliff-hangers like “Perils of Nyoka”, “Daredevils of the West” and “Haunted Harbor”. All of them good.

LikeLike