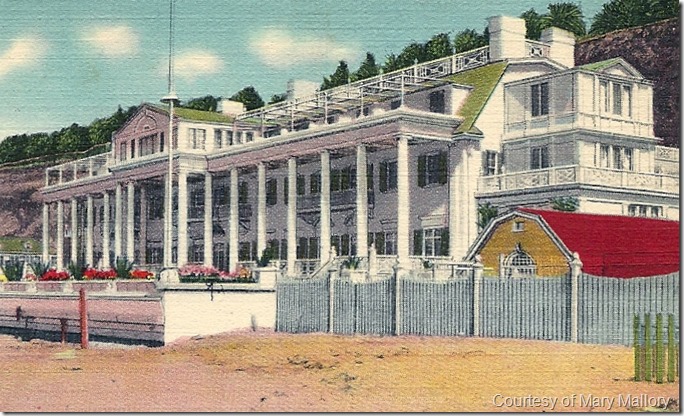

Marion Davies’ beach house, courtesy of Mary Mallory.

Newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst inherited and erected lavish estates for himself around California like Wyntoon, his Northern California retreat, and Hearst Castle, his main residence on the Central Coast, but in 1926 he constructed a mammoth Georgian Colonial home on Santa Monica’s Gold Coast as a present for his companion, Marion Davies. A Hollywood version of a Newport Beach, Rhode Island, “cottage,” Davies’ mansion dwarfed those of fellow film industry notables like Douglas Fairbanks, Harold Lloyd, Harry Warner, and Constance and Norma Talmadge. Davies’ beach house represents the perfect combination of Hollywood excess and elegant architecture.

Marion Davies’ life was never the same after meeting business magnate Hearst. A Ziegfeld Follies girl, Davies’ charming, endearing personality attracted the much older, shyer man. By 1918, the pair were a twosome, though Hearst was married to Millicent, a former showgirl herself. The couple moved permanently to California in the mid-1920s to further Davies’ film career at MGM, and to distance themselves from his wife.

Mary Mallory’s “Hollywoodland: Tales Lost and Found” is available for the Kindle.

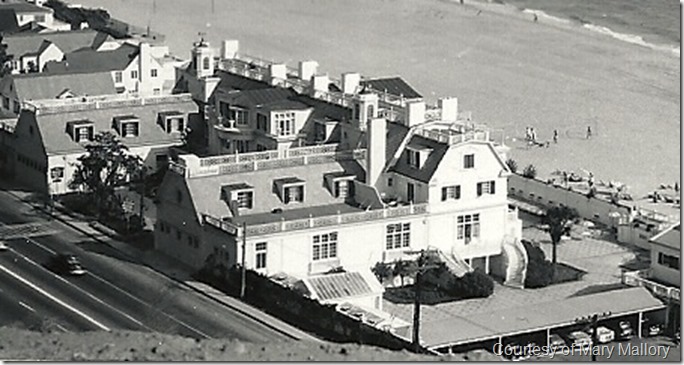

Marion Davies’ beach house, courtesy of Mary Mallory.

Hearst inherited his father’s more than 250,000 acres of ranchland outside San Luis Obispo in 1919, and began transforming the site into La Cuesta Encantada, or “Enchanted Hill.” Assisted by architect Julia Morgan, Hearst erected a lavish palace with 165 rooms and 127 acres of gardens over the next two decades, filled with legendary and historic art, sculpture and furniture acquired on his many trips to Europe. This home complemented Wyntoon, the Gothic, medieval castle constructed by his mother outside Mount Shasta.

Davies and Hearst occupied a home in Beverly Hills whenever she worked on films in Los Angeles. However, many members of the Douras’ family dropped in and out, keeping it crowded and busy. While Hearst and Davies picnicked on the beach one day in May 1926, Hearst announced that he would build her a beach house as a place to escape from family. He hired Morgan to design a regal retreat for his mistress, with the architect supervising construction from 1926 to 1938. Morgan drew up plans for a Georgian Colonial mansion, actually almost three homes in one, on the 21 contiguous lots over almost five acres Hearst acquired on Santa Monica’s beachfront, with an address of 415 Palisades Beach Road.

Marion Davies’ beach house, courtesy of Mary Mallory.

The mansion, which many called a “Western White House,” or an “American legation,” closely resembled George Washington’s Mount Vernon as well as the presidential residence, featuring a two-story portico at its front and a U-shaped Colonial revival clapboard appearance. The huge estate contained 118 rooms, 34 bedrooms, and 55 bathrooms inside the house, along with three guest houses, two swimming pools, kennels and tennis courts. Ocean House quickly became Hollywood’s beach retreat and party central.

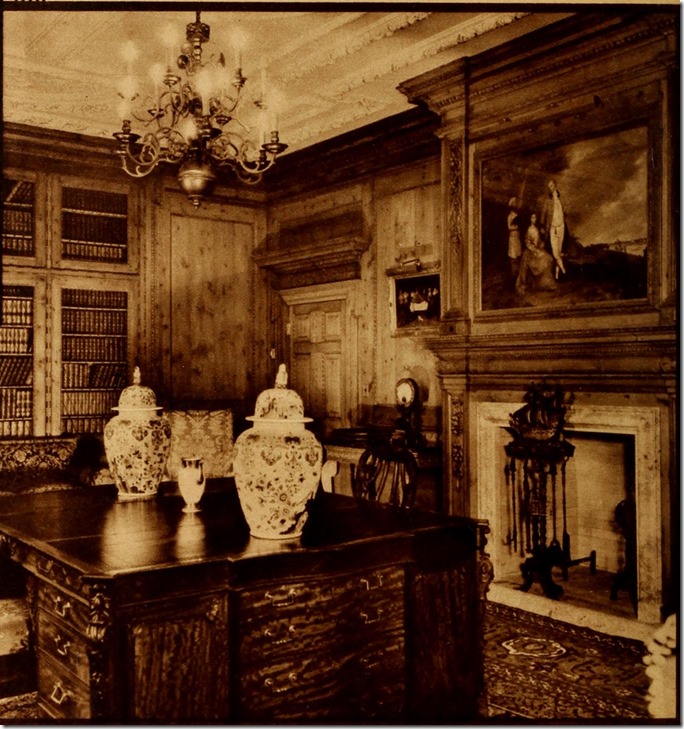

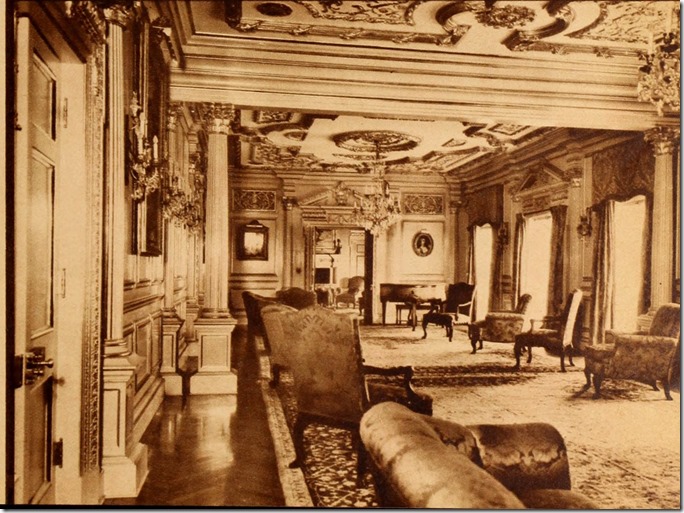

Sam Watters, in his book “Houses of Los Angeles,” states that in 1928, Hearst hired architect and set designer William Flannery to decorate the home’s interior with rich American and English antiques and design. Flannery had designed Joe Schenck and Norma Talmadge’s beach house, and Cliff Durant’s Beverly Hills house. The first floor functioned as the public area for the house, with a reception room, dining room, breakfast room, library, study, long entrance hall and double staircases. The second floor contained bedrooms, while the third floor contained Davies’ private suite, connected by a private staircase with Hearst’s suite below. The ground floor featured a wine cellar, an English tavern nicknamed the “Rathskellar,” changed into an ice cream parlor after an attack by Sister Aimee McPherson, and pool changing rooms. Hearst imported whole rooms from Europe, wallpaper, Grinley Gibbons paneling, paintings and furniture. White marble terraces lined with black diamond tile surrounded the home and grounds.

Marion Davies home, as shown in “Photoplay,” 1934.

Fred Lawrence Guiles states that the house featured 37 fireplaces, Tiffany crystal chandeliers and a dining room to sit 25 filled with Old Masters in his book “The Times We Had.” The library contained a movie screen that rose out of the floor by pushing a button. The gold room truly sparkled, with gold leaf decorating the walls and ceiling, and gold damask sofas, tasseled curtains and Georgian furniture. The Marine Room, lined with English walnut paneling, served as the game room. Davies’ beach house supposedly cost approximately $3 million to build, and almost $4 million to furnish with European furnishings and art.

In the book, “William Randolph Hearst, The Later Years 1911-1951,” author Ben Proctor notes the piece de resistance: a “110-foot heated swimming pool lined with Italian marble and traversed by a Venetian marble bridge.”

Hearst hired 75 woodcarvers to build balustrades and fireplace mantels in 1930 and selected a $7,500 mural wallpaper for Davies’ suite. English walnut paneling lined many of the rooms. Photoplay magazine in 1933 reported that a staff of 20 ran the house, along with the house manager.

Marion Davies’ beach house, as shown in “Photoplay,” 1934.

While Guiles states Henry Clive painted full-size portraits depicting Davies in roles from the films “The Red Mill,” “Little Old New York,” “When Knighthood Was in Flower” that lined the first-floor hallway, photos of some the paintings show illustrator Howard Chandler Christy posing with them, which strongly resemble his artistic style.

Once completed, the beach house served as the wonderful location for many luxurious parties. Elaborate balls and parties like the Circus Ball and a Night in Heidelberg allowed celebrities to play dress up and relax. The home hosted many MGM photo shoots for Davies, her friends and co-stars.

Costs to run and operate the house soared. On July 27, 1939, Davies applied for a reduction in taxes assessed by the Los Angeles County tax assessor when he valued the home at $220,000 and the land at $90,000. Davies asked for a home valuation of $50,000 instead.

Marion Davies’ house, as shown in “Photoplay,” 1934.

During the late 1930s and into the 1940s, Hearst and Davies lived most of the time at Hearst Castle, and stayed at her Beverly Hills’ Lexington Drive home when in town. Davies sold the home for $600,000 in 1946 to the Hearst Corp., which sold it to hotel and real estate magnate Joseph W. Drown. He turned it into an upscale private beach club called Ocean House, “America’s most beautiful hotel,” which opened May 30, 1948, after months of redecorating. The Sand and Sea Club on the grounds required a yearly $1,000 membership fee, per Variety. Minna Wallace threw a red, white and blue ball there on July 3, where suites cost $75 a day. In December, he reopened it as a hotel at rates of $45 a night, with nightclub and special rooms, with society groups, women’s groups, charities, holding balls, parties, fashion shows and events there. Suites could be rented for $225 a month in July 1949, or $255 a month for two persons. Bands performed every night in the Rathskellar. An ad in the Oct. 13, 1949, Variety promoted it as, “A new kind of holiday! Weekend Ocean House parties”—a package from Friday through Sunday for room and all meals.

In 1950, George Marshall directed Eleanor Parker and Fred MacMurray in scenes shot around the swimming pool for “A Millionaire for Christy,” released in 1951. Also that year, director Otto Preminger and agent Phil Berg took up residence for a short while.

Marion Davies’ beach house, as shown in “Photoplay,” 1934.

In May 1956, Drown took out an application to convert the space into a drive-in motel and restaurant, which would require demolishing the house. That July, Drown put the paneling, chandeliers and other items up for auction. The Nov. 2, 1956, Los Angeles Times describes Santa Monica residents and historic groups suggesting that the residence be turned into a museum that would rival the Huntington, only to see the main house and some of the grounds demolished, but the businesses never built. The state of California took over the Sand and Sea Club, which remained open through the early 1990s under the guidance of the city of Santa Monica. The club closed after the Northridge earthquake. A 7,000-square-foot guest house was remodeled and opened in 2009 as the Annenberg Community Beach House, open to the public. The classic look of the building gives it elegance, hearkening back to its glory days in the 1920s.

I believe Fred Laurence Guiles wrote a biography with the title “Marion Davies” and “The Times We Had” was taken from interviews with Ms. Davies

LikeLike

Right. THE TIMES WE HAD was the title of Davies’ memoir, published in 1975, long after her death. It was based on audiotapes Davies made in preparation for an autobiography. Guiles’ biography of Davies was titled MARION DAVIES.

LikeLike

I spent many a day there when it was the Sand and Sea Club! Did read her bio. Sad, when the parties ended her so called friends stopped calling!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mary, a superb job, as always. Talk about a million stories in the city….

One small point: I’m guessing that the hostess of that 1948 shindig might have been Minna Wallis (not Wallace); she was a literary and actors’ agent and sister of the producer Hal B. Wallis, and worthy of a biography herself.

An enduring question about W.R. Hearst is how he could display such taste and discrimination in architecture and design and yet be the proprietor of so many bad newspapers.

LikeLike

I believe you mean “Grinling Gibbons”, not “Grinley Gibbons”

LikeLike