Back in the 1990s, when I began scrounging and scouring for everything I could find on Los Angeles in the 1940s in my research on the Black Dahlia case, I got a copy of Otto Friedrich’s 1986 book “City of Nets” from the Los Angeles Public Library. And, frankly, I was not impressed by the work of Friedrich (d. 1995).

In case you have never read it, “City of Nets” is kind of like this:

“As Oscar Levant was making a left turn onto Sunset Boulevard en route to perform on a radio broadcast with Kay Kyser and Clark Gable, Gary Cooper was having lunch with Igor Stravinsky, Thomas Mann, Marjorie Main and bandleader Xavier Cugat at the Hollywood Brown Derby, where Cugat, having gotten his start as a cartoonist and caricaturist, drew bawdy sketches of his companions on the tablecloth.

“Meanwhile, out in Burbank, on the New York Street at Warner Bros. back lot, director Raoul Walsh was rehearsing with James Cagney and Allen Jenkins for the next shot in….”

For more than 400 meticulously footnoted pages.

It’s exhausting to read, and presumably it was doubly exhausting to compile.

Over the years, various friends, including those whose opinions I greatly respect when it comes to Los Angeles history, have raved about “City of Nets.” At first, I thought they were a bit misinformed, sort of like the cult status that some people give to Kevin Starr (that’s a story for another time), but as the years passed and I kept hearing raves about “City of Nets,” I thought maybe they were onto something.

I picked up a used copy at the Last Book Store several years ago, just to have it in case I ever needed it for something (it was a paltry $5, so I didn’t feel that I was investing much in a book that I considered iffy). And it sat in a pile on a file cabinet for several years.

Not long ago, a friend on Facebook posed the question of what are best books on Los Angeles, and sure enough, there was “City of Nets,” recommended again and again. And I thought, OK, I have a copy, let’s take a look and see if I’m missing something.

The answer is no.

The book is still Oscar Levant making a left turn on Sunset Boulevard while Xavier Cugat draws raunchy pictures of Igor Stravinsky and Marjorie Main at the Hollywood Brown Derby. (You do realize I made that all up as satire, right? Because I wouldn’t want that to appear in some book.)

So I picked a page almost but not entirely at random dealing with emigre Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg for a little fact-checking.

You already know where this is going, don’t you?

“City of Nets” fans, get out your handkerchiefs and prepare to weep.

::

Many years ago, during the second interglacial period, I took a graduate seminar on the music of Schoenberg, although I had forgotten most of the details around the time of the discovery of the wheel. Even so, some of the statements in “City of Nets” sounded implausible at best.

(Bonus fact: I have a recording of our friend Arnold in which he pronounces his name “Shane-berg” as in “Bie mir bist to schoen.” Over the years it has become fashionable to pronounce it Shern-berg, and of course this is the pronunciation you hear on Wikipedia. But he said “Shane-berg.” Really.)

On Page 31 of “City of Nets,” we have Friedrich’s account of poor old Schoenberg, the great composer, coming to the U.S. and being universally ignored by crass, low-brow Americans. Friedrich documents the book with incredible thoroughness, and the footnote for Page 31 leads to three sources: H.H. Stuckenschmidt’s “Arnold Schoenberg,” (1959); John Russell Taylor’s “Strangers in Paradise,” (1983); and Hans W. Heinsheimer’s “Best Regards to Aida” (1968).

After doing historical research and fact-checking any number of books (although they were pretty easy targets, being for the most part in the dubious category of sleazy Hollywood biography), one gets a second sense when an account in a book doesn’t pass the sniff test. Notice that the earliest of the sources (1959) is 26 years after the fact and eight years after the subject’s death, more than enough time for myth-making to set in.

This is a fundamental problem, because a book like “City of Nets,” which seems not to have a single original interview, is only as good as its source material. Meticulous footnotes mean nothing if they only lead to sources that are inaccurate.

Almost 30 years after “City of Nets” was written, we no longer need to rely on these secondary sources used by Friedrich. We can turn to those annoying “first drafts of history” – the newspapers of the era. And they tell an entirely different story.

::

I’m going to skip many statements on Page 31 that would be fun to check except to say that “Pierrot Lunaire” is a ghastly piece of music, and if you have never heard it, you might sample it here.

Our first source will be the New York Times for 1933, the year Schoenberg arrived in America, supposedly given the cold shoulder by everyone, according to Friedrich. In fact, in contrast to the account in “City of Nets,” Schoenberg was heavily covered by the New York Times and given a royal welcome.

We find that on March 12, 1933, the New York Times reported that “Pierrot Lunaire” would receive its New York state premiere in a performance by Leopold Stokowski at Town Hall on April 16.

On March 19, the New York Times again reported on the upcoming “Pierrot Lunaire” performance.

On April 26, New York Times music critic Olin Downes reviewed a performance by the Kroll sextet of “Verklaerte Nacht” at the Library of Congress Festival of Chamber Music in Washington, D.C.

On May 31, the New York Times reported in an item headlined “Prussia Ousts Musicians” that Franz Schreker, director of the High School of Music, and Arnold Schoenberg “have received indefinite leaves of absence as directors of the master composition classes at the Prussian Academy of Arts.

“Both have long-term contracts, the disposition of which will be decided by Bernhard Rust, Prussian Minister of Education.”

On June 11, 1933, in a story dated May 19, 1933, the New York Times noted the “First International Music Convention” in Florence, Italy, with attendance by a stunning array of composers and scholars, including:

Roger Sessions, Darius Milhaud, Albert Roussel, Richard Strauss, Ernst Krenek, Alfred Einsten, Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg, Egon Wellesz, Bela Bartok, Zoltan Kodaly, and the list goes on and on.

A month later, in a story published July 25, 1933, and dated July 24, the New York Times ran an item from the Jewish Telegraphic Agency stating that Schoenberg, 58, “who had abandoned the Jewish faith in 1921, was officially readmitted today in a ceremony at the Liberal Synagogue here with Rabbi Louis Germain Levy officiating.”

Notice the contrast between Schoenberg “abandoned the Jewish faith in 1921” with “City of Nets,” which states: “Though he had been raised a Catholic, and then converted to Lutheranism in his youth….”

On Sept. 8, the New York Times published a story accompanied by a photograph that was headlined:

SCHOENBERG, EXILE, TO TEACH IN BOSTON.

Eminent Modern Composer, Barred From Germany, to Pay Us First Visit.

His Music Familiar Here

Long a Storm Centre in Creative Field — Opera ‘Wozzeck’ the Work of His Pupil, Berg.

Referring to Schoenberg as “one of the world’s foremost composers and teachers of music,” the New York Times said that he would be teaching harmony and composition at the Malkin Conservatory of Music in Boston.

The story profiles Schoenberg’s compositions, his text on music theory and his many pupils, concluding: “The man who is coming to settle, compose and teach in Boston is small in stature, dark of complexion, with sensitive features. He is 59 years of age.”

Notice that before Schoenberg even set foot in America, he already had job, in contrast to the image of nobody wanting to take him in.

On Oct. 31, the New York Times published an item on the impending arrival of the French ocean liner Ile de France. The first paragraph noted the most eminent passengers, including the Belgian ambassador, Artur Bodansky, conductor of the Metropolitan Opera orchestra, Tito Schipa and … Arnold Schoenberg.

The next day, Nov. 1, 1933, the New York Times reported the arrival of Arnold Schoenberg, and gave an account of a brief interview, noting: “The composer, who speaks English fairly well, said he had left Germany of his own accord in May because of the oppression of the Jews. Since then he had resided in Paris. He has been engaged by the Malkin Conservatory of Music in Boston to be a member of its staff and he expressed his pleasure at the prospect of living in this country.”

This is in contrast to Friedrich’s claim that “Only one obscure reporter met his ship in New York.” I think it’s fairly safe to say that no reporter for the New York Times is obscure.

Poor old, friendless Schoenberg, stuck in a foreign land full of ignorant Americans: “City of Nets” says, “The League of Composers arranged a Schoenberg concert in Town Hall, and the audience dutifully applauded even the dissonances that arose from the pianist’s accompanying the singer in the wrong clef.” (I would love to take the time to examine that particular statement, because it sounds ridiculous, but I’ll refrain.)

On Nov. 11, the New York Times reported: “Arnold Schoenberg will be the guest of honor at tonight’s concert of the League of Composers at the Town Hall. An all-Schoenberg program will be played and 50 composers will welcome Mr. Schoenberg at a reception to follow at the Town Hall Club.” Not quite the same, is it?

I can’t seem to locate a review in the New York Times. But wait. Here’s one in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

Our critic, Edward Cushing, paints an interesting portrait of the concert and the audience. And rather than not noticing the dissonances when a pianist allegedly misread a clef (at least according to “City of Nets,”) Cushing says he is all too familiar with the works on the program.

He says: “One has heard and reheard the string quartets and the early songs and piano pieces often enough not to care particularly whether or not one ever hears them again.”

Whew. Research is tedious work.

::

Our stroll through the New York Times has already undercut the account in “City of Nets” (you knew it would, didn’t you?)

And I could happily stop here, but I’m quite curious about the claim that not a single student signed up for Schoenberg’s classes. Given his royal welcome by the New York Times (and remember that there were other papers that could still be examined), it’s hard to imagine that he wasn’t swarmed with eager students.

We find a Feb. 14, 1935, item stating that Schoenberg was going to join the Juilliard faculty for the 1935-36 school year. Curiously, there’s not a word about that in “City of Nets,” which hammers away at nobody wanting to take in poor old Schoenberg. That would be another interesting thread to pursue, but I’ll let it go.

It’s worth noting that Joseph Malkin’s Sept. 3, 1969, obituary states: “When he founded the Malkin Conservatory in 1933, one of the first things he did was bring composer Arnold Schoenberg to this country to teach there. The school remained under Mr. Malkin’s directorship until it closed in 1943.”

Let’s keep looking. I’m positive that the claim that “not a single student registered for the composition course Schoenberg offered” cannot possibly be correct.

Aha! Just as I thought.

Thank you, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Oct. 22, 1933.

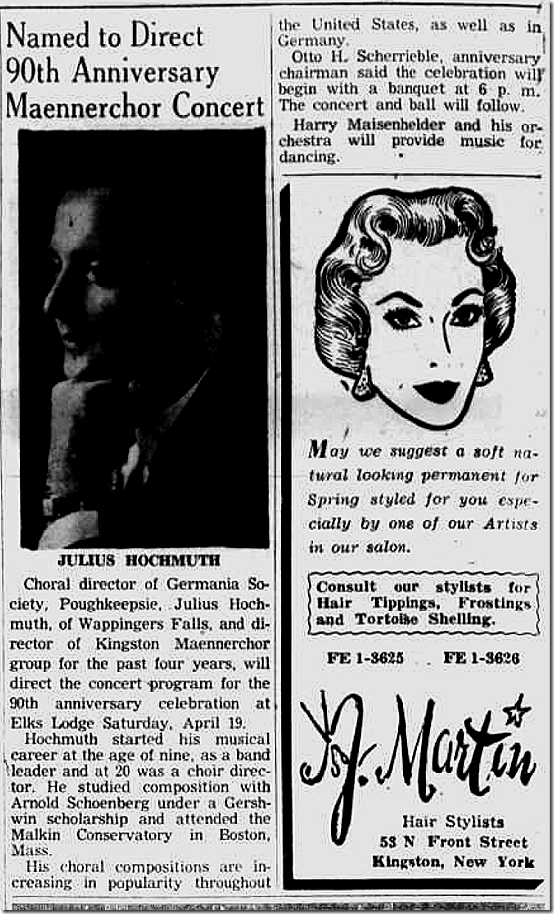

And here’s one of his students from Malkin, thank you Kingston, N.Y., Daily Freeman, April 8, 1959.

To be sure, neither story refers specifically to registration for his classes, but it’s safe to say, based on these accounts, that students were clearly eager to study with Schoenberg and it’s most unlikely that no one registered for his class in composition or theory.

::

I’ll be generous to my friends who champion “City of Nets” and concede that one shouldn’t condemn an entire book on the basis of fact-checking one page and indeed only a few facts on that page.

But the major errors that turned up by examining contemporary news accounts underscore the challenges of relying on these derivative sources, as Friedrich did. A book can only be as good as its raw material.

Garbage in, garbage out.

As for me, “City of Nets” goes back in the pile, too good to throw away but too unreliable to actually use except as an example of what not to do.

Another good story ruined.

Credit to fultonhistory.com, a fabulous source of online newspapers, which made this research possible.

I don’t know anything about Schoenberg–but I do know I am heading to A. Martin’s on Front Street for a soft, natural-looking perm for spring!

LikeLike

I haven’t enjoyed a piece of yours as much since your series on Hodel and Buster the Wonder Dog….

LikeLike

I haven’t enjoyed a post as much since your series on Hodel and Buster the Wonder Dog….

LikeLike

my knows-it-all musician husband said schöenberg could NOT be pronounced that way!

i tried to tell him that when it comes to names, all rules go out the window.

LikeLike

To be honest I was shocked when I listened to the recording of Arnold and heard him pronounce his name

“Shane-berg.” But believe me, that’s what he said.

LikeLike

Too bad such a charming idea of tying simultaneous acts by various masters of their craft in the city of manufactured dreams was wasted by shoddy writing.

LikeLike

Thank you, Larry. I hope you’ll also blow to smithereens the well-established legend of Los Angeles being a cultural wasteland in the 1930s. Look at any issue of any L.A. newspaper of the period and you’ll see an abundance of lectures, art shows, salons, musicales, live theater, and more.

LikeLike

That’s a stereotype that has been perpetuated by New York writers for more than a century. It’s quite amazing, really.

LikeLike