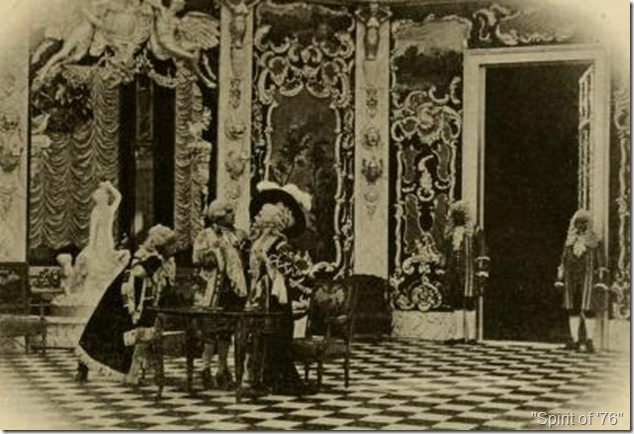

A still from the lost film “Spirit of ‘76” from Moving Picture World.

The United States’ Espionage Act was ratified in 1917 to punish those abetting the enemy, promoting military insubordination, or interfering with recruitment. Over the years, it has been amended to include punishing for the disclosure of secret information. For good or ill, such individuals as Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, Daniel Ellsberg, and Bradley Manning have been convicted under its statutes. One of the first people to be ensnared after its creation was filmmaker Robert Goldstein, producer of the 1917 patriotic film, “Spirit of ’76.” A film he intended to unite Americans in pride instead became a tool for destroying his life.

Born in San Francisco, Robert Goldstein was the son of Simon Goldstein, the owner of one of the United States largest costume and wig making businesses. This connection enabled young Goldstein to meet many early moving picture performers, like D. W. Griffith, Lillian and Dorothy Gish, Henry Walthall, Mae Marsh, and others. Motion pictures thrilled him so much that he moved to Los Angeles in 1912 and established a branch of the family’s costume businesses, providing wardrobe for the film industry.

In 1916, 34-year-old costumer Robert Goldstein decided to produce a patriotic film showing America triumphing in the Revolutionary War. Employing profits he had earned from investing in D. W. Griffith’s landmark 1915 film, “The Birth of a Nation,” Goldstein hoped to capitalize on Griffith’s success with a patriotic movie revealing a young nation pulling together to achieve victory in the 1770s. This film would be titled, “The Spirit of ’76.”

Goldstein incorporated the Continental Producing Co. with George Hutchin in 1916 to write and direct the picture. A June 14, 1916, “Moving Picture World” story stated that the film was “to be perfect as to its historical accuracy and detail, with an entirely original and sensational story closely interwoven.” The heart of the story focused on George III’s mistress Catherine Montour’s efforts on becoming “Queen of America.” The film featured such historic events as Paul Revere’s ride, Washington crossing the Delaware, Valley Forge, the signing of the Declaration of Independence, and the British massacre and atrocities committed to American settlers in the 1778 Cherry Valley Massacre.

Director Goldstein hired actors such as George Chesborough, Adda Gleason, Howard Gaye, Jane Novak, and Noah Beery. Gaye, who had played General Robert E. Lee in “The Birth of a Nation,” and Christ in “Intolerance,” was loaned out for the film, which he considered “quite a good picture” in his unpublished autobiography, but which suffered from financial problems during its production. The film shot scenes at Chatsworth, Idyllwild, and at Mt. Lowe. Novak told historian Anthony Slide, “Everyone in the company was constantly excited and thrilled by what we expected to be one of the greatest films. D. W. Griffith came several times to see our sets and watch a bit of our work.”

Upon completion, Goldstein bought an ad in the April 7, 1919, “Moving Picture World,” which stated that the film had “happily completed at this time to help rouse the patriotism of the country.” He chose Chicago to premiere his $250,000 film on May 17, 1917, a few months after the United States joined the first World War, leasing Orchestra Hall and hiring 39 members of the Chicago Symphony to accompany his production.

The press attended an advance screening and raved about the film. The Chicago American stated, “Chicago is honored by being the premier city for the showing of “The Spirit of ’76.” Never before has there been screened a history, romance, adventure, story picture in such perfection. It is a stage classic. It is the very heart of what our patriotism is based on.” The Chicago Examiner claimed, “It breathes freedom.” The Exhibitor’s Trade Review noted, “It has some wonderful moments and should cause the red blood of any American to tingle,” and that “Everything is action, action, action…The picture is a succession of thrills.” They also noted it was too long and more trimming was needed.

Chicago’s police board censor Major Funkhouser objected to “The Spirit of ‘76.” He had earlier censored Mary Pickford’s “The Little American” for being offensive to Chicago’s German population. He barred screenings of the Goldstein work. Goldstein challenged the decision in court, with Judge Kavanaugh ruling that the picture was not anti-British, but that it could only be screened if objectionable scenes such as a British soldier pulling a female settler by her hair, and another with a soldier knifing a baby, were cut. The film played to packed and enthusiastic audiences, who sometimes drowned out the orchestra with their effusive clapping for the triumphant American scenes. It closed one day before the Espionage Act was passed on June 15, 1917.

‘The Spirit of ‘76” next ran in New York City in July, through an arrangement with the Pincus Brothers. The National Board of Review passed it with only a few simple cuts to be made.

Goldstein booked Clune’s Auditorium for the Los Angeles premiere on Nov. 28, 1917. Lillian and Dorothy Gish, Bobby Harron, and Henry Walthall witnessed an early screening of the film, where crowds went wild when they spotted a giant flag hanging on the back wall after the curtains opened. Most of the L.A. papers praised it. The Los Angeles Daily Times called it “Fairly astounding in scope, magnificent, spectacular, thrilling, its chief fault being its perhaps too great wealth of incident…If you want to see the most startling picture of the year, don’t miss “The Spirit of ’76.”

Sid Grauman warned Goldstein right before Thanksgiving that he had heard the film was going to be shut down that night. Newmark, Clune’s manager, told him that the Los Angeles Times considered the film pro-German propaganda and were going to shred it. On Thanksgiving night, Dist. Atty. O’Connor appeared with a writ and search warrant, seizing the film, claiming that Goldstein had reinserted the cut scenes of British atrocities. The Federal grand jury indicted him on three counts for “intent to commit mutiny, insubordination and refusal of duty in military and naval forces in aid of the Imperial German Government.”

Goldstein was immediately thrown in jail, and his terrible troubles began. Naïve, trusting Goldstein thought that he was producing a patriotic film showing a young American nation overcoming struggles to emerge triumphant. His government, on the other hand, overreacted and considered the film a threat to our allies and supporting the German cause. Once the government condemned it, the press branded him a traitor, and a more innocent American public, with complete trust in their public officials, turned their backs to the long-suffering man.

To try to punish Goldstein, the Federal Government violated some of the basic principles on which this country was founded, particularly that of free speech.

The filmmaker paid a huge amount of bail to get out of jail, and struggled to find an attorney willing to defend him in court. Earl Rogers took money as a retainer but then reneged on serving him. Goldstein hired James Ryckman, a socialist, as his attorney, thinking he would stand up to the government.

The trial began April 3, 1918, in front of Federal District Judge Benjamin Bledsoe. Virtually the entire jury possessed one family member in military forces, or waiting to be drafted. Papers began ridiculing the film. Compatriots seemed to turn against him immediately, with Hutchin declaring that Goldstein told him that Franz Bopp, former German Consul in San Francisco helped finance the film and that he hoped to produce a pro-German film. Goldstein himself took the stand on April 18, and papers humiliated him with taunts that he couldn’t be heard. Goldstein later claimed that after the jury adjourned, they were taken to the Alexandria Hotel for a champagne party, where they reached their verdict.

On April 29, 1918, Goldstein was found guilty on two counts and fined $5,000. Moving Picture World on May 25 revealed that Judge Bledsoe “verbally excoriated him for his unpatriotic conduct,” and told him “that he had not only lied on the stand when he testified in his own behalf, but that his conduct on that occasion was most despicable.” The judge believed the case concerned the destiny of the nation during the time of a national emergency. The Judge sentenced him to serve ten years in the Federal Prison at McNeil’s Island, with a two-year sentence to run concurrently. Goldstein stood as a pariah to the government, betrayed financially even by his own family. His wife divorced him. President Wilson took a small measure of pity on Goldstein, commuting his sentence to three years and waiving the fines on March 6, 1919.

Judge Bledsoe saw that the seized film was re-edited to six reels and released under the title “Heats Aflame.”

Harvard Law Professor Zechariah Chafee, one of the premier scholars focusing on free speech and civil liberties, employed Goldstein’s case in his 1920 book, “Free Speech,” considering it a grave injustice that the ruling denied the filmmaker free speech for a film highlighting the American cause, and ignored banks and boards of directors’ involvement with the film.

Newspapers and trade magazines continued character assassination on the man. The August 1918 Photoplay called him, “A bumptuous ignoramus, more fool than villain.” The Aug. 6, 1921, Moving Picture World called the film “a crude concoction of fact and fiction.” Green Room Jottings called it “Pro-German propaganda.”

Goldstein suffered even after being released from prison. His family shunned him. No attorney would represent him in appealing the court decision. He couldn’t find a job.

In 1921, Goldstein met with J. T. Adams, the Republican Centennial Committee Chairman, in Dubuque, Iowa. Adams gave him a letter to present to U. S. Atty. Gen. Daughtery in Washington, D. C., who refused to meet with him. Goldstein walked the Senate Office Building and met with senators asking for help, but none rallied to his cause.

Goldstein re-cut the film for the All-American Film Co., who screened it in successful showings in New York’s Town Hall for three weeks during the summer of 1921. Unfortunately, all reviews mentioned his prison sentence and decimated the film.

Unable to find work, a destitute and despairing Goldstein departed the United States in October 1921 for a promised film job in Holland. When that fell through, he moved to Berlin to live with aunts. Goldstein continued searching for work in Italy, Switzerland, Germany, and France. His past haunted his projects, ruining any chances of work or help.

Actress Jane Novak ran into Goldstein again while filming in Berlin in 1924. She noted that he was “the same gentle, soft-spoken man I had known so many years before…”

Goldstein wrote Secretary Frank Woods of the fledgling Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1927, appealing to their sense of justice in helping him obtain an attorney to vindicate his name and to find a job. He wrote a series of letters, before sending a somewhat rambling and paranoid 92-page manuscript written in the third person documenting the full history of the case. He claimed conspiracies had destroyed both his film and his life, and stated there was no political intentions in making the film. He thought his attorneys had unfortunately done more to convict him than anyone else.

As Tony Slide notes in his book, “Robert Goldstein and The Spirit of ’76,” Woods wrote back on behalf of the Academy, “The Academy has no power nor funds to employ an attorney for anybody, however worthy the cause, and your claims are such that they could be settled in no other way. As for circulating the statement among the membership I am advised that this would be making myself and the Academy responsible for all the charges contained therein which I cannot undertake to do.”

Over the next ten years, Goldstein would occasionally write AMPAS about various matters, but no further correspondence is contained in his file beyond 1938. Who knows what happened to the defeated and destroyed man?

Robert Goldstein’s film, “The Spirit of ‘76” is lost, but stills show a handsomely mounted production. From reviews, it was an important spectacle of the time, viscerally speaking to the public. The case unfortunately demonstrates the frightening aspects of government overreaction and condemnation of an innocent man, and the willing complicity of the public in denying freedom of speech and imposition of censorship.

Goldstein ended up in Germany, and was trapped there when WWII broke out. His fate is not known with absolute certainty, but one source says that he “most likely” died in a concentration camp.

LikeLike

Oops! A bit of further research – the text and origin of that final 1938 telegram – suggests that Goldstein did *not* die in Germany. First, he sent it from New York; and in it, he refers to “…my enforced return here, three years ago…” suggesting that he was deported by the Nazis. From there, the trail goes cold, but if he stayed in NYC my newspaper’s dusty archives may have further information.

LikeLike

There is a letter in the AMPAS file from 1938 with Goldstein at the Hotel Continental in New York. I don’t think he would have gone back to Germany at that point, since Jews were in terrible straits by that time.

LikeLike

The only things that seemed to come up for Robert Goldstein in the LAT/NYT from the 1940s-1960s was for the Fox executive Robert Goldstein, a different person.

LikeLike

This fascinating story about ugly acts of politics by our government and a complicit media seems oddly contemporary.

LikeLike

On top of everything else, he was unable to argue for protection under the First Amendment, because the Supreme Court had ruled in 1915 that motion pictures lacked such protection. (That ruling was overturned in 1952, of course.)

LikeLike

What a sad, disgraceful,yet fascinating story. Thanks for writing it.

LikeLike

Thank you for writing such an interesting article. I recall reading somewhere that Goldstein had also written to a professor at Columbia U. pleading his case and sometime subsequently suffered a nervous breakdown ending up at Ricker’s Island psychiatric ward where I think he died. It might be possible to research Ricker’s Island’s hospital records to see if they still retain the history of his stay. It remains such a tragic chapter of our history to have scapegoated this poor man and ruin his life.

LikeLike

Pingback: Week of September 16th, 1916 – Grace Kingsley's Hollywood

I visited the New York City Archive and I found only a dead end. Their records for Rikers Island end in 1936. I also checked the burial records for Potters Field but they’re kept by death date, and they’re missing the microfilm reel with records for 1942-1943. He did have a social security number and he made a claim in March, 1940. Maybe someday more records will be digitized and we can find out what happened to him.

LikeLike

Does Lisle Foote or anyone else have Mr Goldstein’s ss#? More details about his March 1940 claim? Wife name and divorce info? I’m a retired professor and would like to research this mystery further. Thank you.

LikeLike

Does Lisle Foote or anyone else know Mr. Goldstein’s actual ss# from the 1930s? Have info on his March 1940 correspondence with Social Security? Know details about his wife and their divorce? I am a retired professor and would like to further investigate these mysteries about him. Thank you. Richard Alan Nelson, Rnelsonlv@gmail.com

LikeLike