Photo: Dick Lane with Laurel and Hardy in “The Bullfighters.”

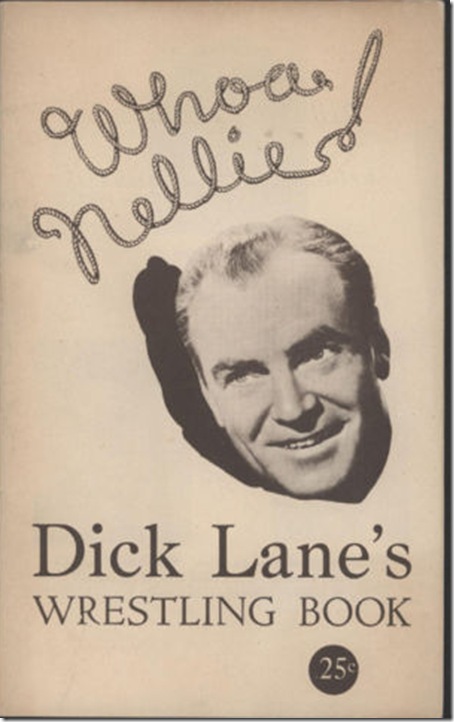

This is Part 5 of James Curtis’ 1975 interview with Dick Lane. In this segment, Lane discusses Laurel and Hardy, Abbott and Costello, making “Wonder Man” with Danny Kaye and George Balanchine, and genesis of pro wrestling on TV.

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

JAMES CURTIS: You were with Channel Five for what must have been at least twenty years…

DICK LANE: Thirty years… Yeah, thirty-one years.

JC: Must be a record of sorts.

DL: It was a wonderful experience.

JC: Getting into the latter part of the forties, you worked more and more in television, less in films.

DL: That’s right. I made up my mind to hang onto one until the other got to be commensurate to what I could make. When television came up to what I could make in pictures or beyond, then I’d drop pictures. And it came out just that way.

JC: In the mid-forties you made two of Laurel and Hardy’s last pictures.

DL: Yes, “The Bullfighters” I think was one of the last ones.

JC: That was their last American film. And then earlier was “A Haunting We Will Go.” After they left Hal Roach, it seems their films never had much of what they had in their prime. Did you sense any kind of frustration on their part?

DL: Yes, there was. Because Ollie and Stan weren’t as close as they were under Roach. Ollie had his little things that he liked to do–he liked to play golf and hang around Lakeside and Stan didn’t. And as a result they didn’t associate with each other except on the sets. And they lost that little something that they had under Roach, I think. That was the way I saw it. But they were delightful people to work with.

JC: Were they ever frustrated by things they wanted to do that they couldn’t?

DL: Yes. Oh, yes. So many times… I remember one time–I can’t remember the director’s name–

JC: Mal St. Clair?

DL: Mal St. Clair… At that time, Bill Koenig was the supervisor of the studio, the superintendent of the whole thing over there, in charge of operations. He came on the set one day when we were making one of these pictures, “A Haunting We Will Go” or “Bullfighters,” and he was raising the devil because we were five pages short. We were behind schedule. And Mal said, “Five?” He grabbed five pages and he tore ‘em out of the script and said, “We’re right on the money, Boss!”

JC: Were the pages ever shot?

DL: Nobody ever missed ‘em.

JC: Could you see any creative juices flowing when they were on the set?

DL: Yes! Stan was actually the creator. He was the fellow that had the ideas. And big Ollie, he’d go along with a gag as long as he could finish up with his line. He had to read the kick line. And Stan would do a little crying.

Photo: Laurel and Hardy with some eggs in “The Bullfighters.”

I remember the one scene I was so crazy about; they were shooting it, and there was no way of writing this scene. A scene at the bar with the girl with the eggs. Finished up with the eggs in the shoes, hittin’ each other with these eggs. There was no way you could write that scene. So the only thing to do was set up a camera and say, “Go ahead. Let’s see what you’re going to do.” And they let it run. And how long can you let one scene run?

Like sittin’ on the edge of a fountain and flickin’ water at each other–flick with one hand, then flick with the other… Pretty soon they get a hat full of water… then a bucket of water… eventually they throw each other in the pool. But when they started smashing these eggs, and this girl went along beautifully–she didn’t know what they were going to do, so she didn’t break up. She knew there was some point where they’d stop, but she didn’t know where it was so she didn’t dare to break up.

JC: About that time also you worked with Abbott and Costello at Universal.

DL: Yes.

JC: Was the atmosphere different when making one of their films as opposed to Laurel and Hardy?

DL: Oh, yes. Yes, they were–

JC: Would you compare them to Olsen and Johnson?

DL: Well, they were more like Olsen and Johnson than they were like Laurel and Hardy. They did freaky things, you know. But probably the greatest straight man that ever was was Bud Abbott. Probably never was a better one. I remember a line. Whenever they were talking about who was the better of the two, what could one do without the other, Abbott one time said, “I can make anybody funny. I could paint a comic on the back wall and make him funny.” Well, I think he could.

JC: Who was the brains of that team?

DL: They had a man by the name of John Grant who did most of their writing. He was an excellent writer, and he knew them. When he wrote something, he wrote it seeing them say it. You know? He knew what Abbott would say and what Costello would say. So he wrote things that they would say; the same dialogue would sound foreign coming from any other two guys. Johnny Grant knew them well, and he had written for them in burlesque and in radio. In radio, of course, he wrote in sound effects, but in pictures you had to really do it.

JC: I guess you went to Goldwyn for a while, also. “Wonder Man” was Goldwyn, wasn’t it?

DL:“Wonder Man,” yes. With Danny Kaye.

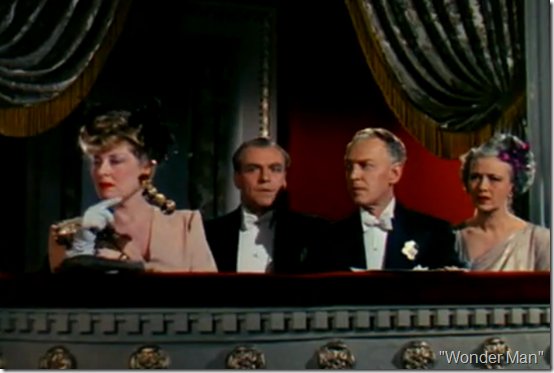

Photo: Dick Lane watches Danny Kaye perform in an opera in a cutaway shot in “Wonder Man.”

Oh, there are some very funny things that happened on that picture. We had already shot the finale of “Wonder Man.” The story finished up at the opera–do you remember the picture?–and it was a bad finish. The picture laid an egg when we got to the finish of the thing because it had no finish. And the only thing it needed was choreography for it–movement of the people around so that it was believable.

The music was great, the songs were good. Danny Kaye–who wants anything better?

So they decided to bring on a choreographer, and Goldwyn wanted the best–George Balanchine. So he talked to him and his agent on the phone in New York, and it was agreed that he was going to do it. So they sent him a script air mail, and he must have read it on the plane coming out because he came directly to the studio.

And if you remember, we had the scene for the finale in a café, with the checkered tablecloths and the salt and pepper and the condiments and things. Balanchine came right onto the set. Danny Kaye and a bunch of us were sitting around talking with him. And the assistant had called Mr. Goldwyn and said, “Mr. Balanchine is here.”

So he hurried down, and he came over to the table. And he sat down at the table with us, right opposite Balanchine. Nose-to-nose with him. And he said, “Well, come on, what’s your idea?” Balanchine said, “I’ve just arrived.” Goldwyn said, “You read the story?” He said, “Yes.” Goldwyn said, “Well, what are you going to do?” But right off the top of your head, you can’t jump in and say, “This girl’s going to do this, and that girl’s going to do that.” He hadn’t blocked anything out.

Goldwyn said, “Well, come on. Start talking. What is it? What’s your idea?” Well, he looked helplessly around at us. You know, What do you do with this fellow? Goldwyn was insisting: “Come on. Talk. What do you say?” Balanchine said, “Well, some things are positive, and some things are negative.” Goldwyn says, “Yeah, yeah. Now you got it. Go ahead.” Balanchine picked up a salt shaker and said, “Let’s say this is a negative… ” and the pepper shaker “… and this a positive… This is a negative and this is a positive and, well, there you are.” Goldwyn looked at it a moment and said, “I like it. Go ahead!” Balanchine just fell backwards off his chair, and Danny Kaye, I thought he was going out of his mind.

Balanchine said, “I’ve heard of these Goldwynisms, but I would have never believed this possible if I hadn’t seen it and heard it.”

JC: Was Goldwyn much like the legend? Or was that exaggerated?

DL: Oh, a lot of things he was given credit (or blame) for probably never happened. Somebody always had to be around to bounce these gags off. Probably more credit has been given to Joe Frisco for lines he never said than anyone else. He was another funny guy.

JC: During that period, they needed a double for Lionel Barrymore in “Duel in the Sun” and they got you for the long shots because you were a horseman and you looked like Lionel Barrymore?

DL: That’s right.

JC: How were you approached for something like that? Had you ever done doubling work?

DL: Never. And it’s a funny thing–in addition to that, I played a part. I could come to within twelve, fifteen feet of the camera and still they wouldn’t know it wasn’t Lionel Barrymore. Except for the position of his hands; he was badly crippled from arthritis at the time. He was in a wheelchair, too. That’s another reason–I could sit down and didn’t have to walk like him. I played a part, and I established a raise in salary for playing this part, too. But when the picture was shown, I wasn’t even in it.

JC: You’re not even in it as a double?

DL: Oh, as a double, yes. Francis McDonald and I walk into a barn where a barn dance is supposed to be going on, and that’s the beginning and the end of my acting part. And I was on the picture almost 14 weeks.

JC: Fourteen weeks??

DL: Yeah. Talk about finishing up on the cutting room floor. I got fan mail from the mice.

JC: Did you ever have any experiences with Selznick?

DL: He was never around the set. Rarely, if ever. But these edicts would come down. He was a great man for sending down directives. They weren’t rules or anything, they were what he called directives–“It will be required of you to do… ” And “required” means you’d better do it.

JC: Did he still have the old RKO-Pathe studio?

DL: Yes.

JC: Was that film mostly shot on the back lot?

DL: Most of this was on location.

JC: Where did they shoot?

DL: Up at what would now be–well, we called it Lasky Mesa at the time. Sylmar. You know where Sylmar is?

JC: Sylmar. Yeah.

DL: It’s in that area. Where that railway was built, and where we built the fence that was such a big thorn in everybody’s side, it’s just one solid mass of homes. A real estate development on that whole thing called Lasky Mesa. Because that’s where Lasky–Paramount–used to shoot all their westerns.

JC: Did they make a lot of pictures up there?

DL: Oh yeah. There was a great prairie for prairie scenes.

JC: Do you remember problems specific to making Technicolor films back in those days? Was there a lot of extra time required for lighting?

DL: Well, yes, because it took printing. The printing was difficult, because sometimes the red would dominate, and for another hundred feet the blue would dominate, or the yellow. The three basics. But it all had to be corrected in Technicolor printing. The Kalmuses, if you’ll remember. Many times a picture would have to be–what do you call it?–re-developed. On one section of the film the reds would have to be brought up, at another place they’d have to be subdued. Things like that. It took a tremendous time. And you didn’t see your dailies often enough.

JC: You would see the dailies, I’d guess, in black and white…

DL: Black and white, yes. But you couldn’t see them in color. That’s all obviated now with television. You can run a television camera right alongside of it with a tape machine. Play the scene once, run it back on television, show it on the monitor, then you can see whether the scene was worth anything or not.

JC: Have you ever worked that way where they had a replay system on the set?

DL: Only once, on a picture with Jerry Lewis. A thing called “Visit to a Small Planet.”

JC: When you worked out of films and into television more, you started with the wrestling matches.

DL: Oh, yes.

JC:With Gorgeous George, for instance. Late forties, early fifties?

DL: Around 1947 or ‘48… He came out around that time.

JC: How did you get into wrestling? And later on Roller Derby?

DL: Well, I was with Klaus Landsberg on television, and we got to looking around for something to do to fill the time once we became commercial. Sports are wonderful, but most sports are seasonal. The one sport that is not seasonal, that runs 52 weeks a year, is wrestling. Fifty-two weeks a year. And now, you could say boxing also. But wait a minute–in boxing you can’t popularize a man as quickly as you can in wrestling. In boxing, you don’t see him every week, the same man. In wrestling you can.

So we talked it over, and I said, “Klaus, I’ll tell you what I want to do. I’d like to take a crack at wrestling.” And I told him why–because it’s 52 weeks a year. And no job to shoot it; an amateur can shoot it with a camera. Where do you have to go? Twenty-two feet by twenty-two feet? No panning, no great camera tricks. He said, “Alright, see if you can get into the arena.”

So I went over to the American Legion stadium, and I tried to get in over there. They ran me out of there. They said, Get outta here, ya bum! “If you’ll buy all the empty seats, yeah. If people can see it on television, they won’t come in here.” Get outta here! So I went out. And I told Klaus about it. He said, “Well, there’s another one. Go down to the Olympic.”

So I went to the Olympic, and Cal Eaton gave me the same routine. He said, “Go away Buck Rogers and all your cameras. Get outta here!” So Klaus is stubborn. That Dutchman was really stubborn. He said, “Alright, we’ll stage it. Right in our studios.”

In that funny little studio we put up a ring, and the ring was ten by ten. Now this is the god’s truth, because we had pads–two five by ten pads, wrestling pads. We put them together, and we built a ring with rope–regular rope–run through corner posts, which were stage-screwed to the floor. And we put on two boxing bouts and two wrestling bouts on a Thursday night. Two three-round boxing bouts, and two fifteen-minute wrestling bouts.

Now, we had no room for an audience, because the cameras had to go out in the hall. And so the audience we had was one cameraman cheering the hero and the other was booing the villain. And it sounded just about like that. So we got some records–some sound effects records with crowd noises–and we’d run those under it to kind of sweeten it. And during that time I proved to the wrestling profession that we could do a workman-like job of presenting their game.

I had my choice of two things–to poke fun at it (and if there’s any wrestling in there you’ll have to find it yourself) or point up the competitive angle of wrestling and just let the hippodroming happen with tongue in cheek. And it paid off that way. And as a result, I did wrestling for twenty-eight solid years. And I never lost a friend of a wrestler because I never violated their game.

JC: That was important to them.

DL: You betcha.

I’ve never heard of Paramount having a ranch out at Sylmar. The first ranch was where Forest Lawn Hollywood Hills is now, and then the ranch out at Topanga, which is now a park.

LikeLike

Mary, you might be confusing Lasky Mesa with the Paramount Ranch. I believe they were two separate places.

LikeLike